I write quite a bit about being a Christian in the midst of American patriotism and the effects of various identities and allegiances on life and faith. I'm not sure I need to go into that much here today - if you want you can read a relatively recent post that touches on the subject.

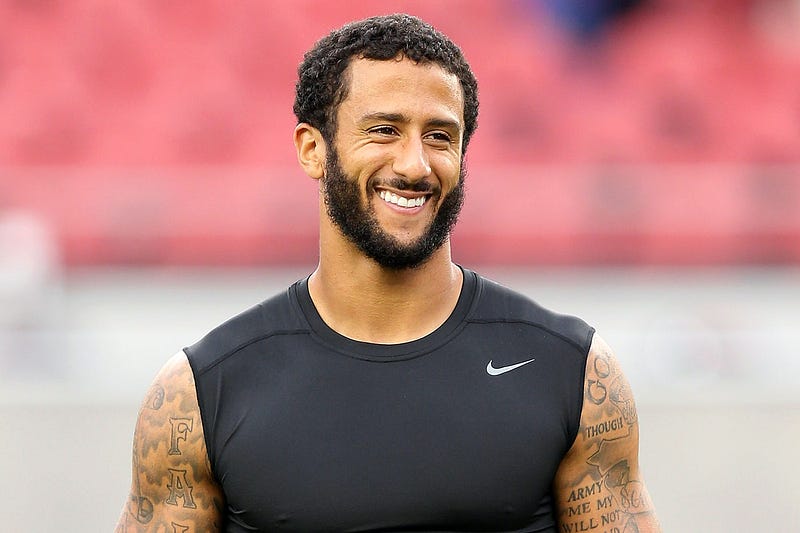

I do want to offer some personal reflections on the topic of the national anthem as its been in the news a bit this week. San Francisco 49ers quarterback, Colin Kaepernick was photographed sitting down for the national anthem at a recent preseason game. When asked, he said he was doing so as a protest to racial inequalities that exist in the US, specifically to highlight accountability that's not taking place.

Here's a pretty basic summary.

There have been heaps of comments from people all over the political and cultural map making comments about what Kaepernick should do - some very supportive, some in opposition - still others who seem to just enjoy hearing themselves speak. For me, I think those who comment on the situation as a whole and not on one person or one action have the most reasoned and agreeable positions. Here are two I resonate with: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Jim Wright, a retired member of the US Navy. Both men eschew comment on Kaepernick or his protest and instead focus on the broader subject of protest and patriotism in the US. This seems much more healthy.

As someone who does not feel comfortable pledging allegiance to a nation for a host of (oft discussed) religious reasons, what struck me from this episode was how often people wanted to give Kaepernick advice on decorum. Probably more often than not in those opinion pieces, the author ends up saying, "I can respect his anger and his desire to protest, but this isn't the way to do it; he should still honor the flag."

It's odd that these statements both me, because it's essentially what I've decided to do. When I'm at an occasion where the pledge of allegiance is recited or the national anthem played, I generally stand, with my hands behind my back and my head bowed. I don't feel comfortable participating in such displays of nationalism, but I understand the moment is important for those around me, even if I wish it were less so. I don't want to be a distraction or detraction from what is an important ritual for others.

I guess that's the part that makes me leery of this "advice" Kaepernick is getting. It's essentially sympathetic people expressing their desire not to make waves during patriotic events. I get the sentiment and they're certainly entitled to an opinion, but isn't that the point of protest? To make a scene, to unnerve people you feel to be too comfortable? A protest is, by definition, a disruption.

As far as protests go, this was a pretty quiet one. Kaepernick isn't a starting QB. He's no longer the star of the team. What's more he never sought out a platform to make a public statement. He's embraced the opportunity, sure, but only because he was asked. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the sprinters of the famous black glove protest at the 1968 Olympics are, now, generally lauded as heroes (even if they were kicked out of the Olympics at the time) for a much more obvious and disruptive protest. I can't imagine it's Kaepernick's failure to stand up that's really a problem for most people.

Symbols are tricky. The flag and the anthem and so many other "patriotic" things mean something to people - they represent something more than themselves (which is the definition of symbol). When things mean a lot to us, it's real difficult for us to imagine they mean something else to someone else - or worse: nothing at all.

This is why I try so hard to safeguard my identity. It's easy for us to get our own selves, our own sense of worth and rightness tied up in the symbols we value. If we see ourselves as people of sacrifice and loyalty and hard work, it's easy for us to attach those things (and thus ourselves) to a flag or a nation or a cause or religion.

It also works the other way. I try hard not to let my image of someone else get too caught up in identities. Whether it's Kaepernick and his difficulties with the US and its symbols - or those people who speak most harshly against him while wrapped in the (sometimes proverbial) flag. Patriotism and Protest are both symbols people cling to; they are as much identities and symbols as those things they set up in opposition to themselves. I think it's good practice not to buy into that mode of thinking, but to see and treat people as unique individuals, separate from any group or notion they may associate with.

That leaves Colin Kaepernick as a still relatively young guy who's struggling with some difficult issues. He's a biracial man, raised by adoptive white parents seeking to be a leader in a culture and world that (largely) sees him as a man of color. He's attempting to stand for and demand justice in the best way he knows how - with some varying degree of success and failure.

Let's all try to hold the reins a bit, here; avoid putting him into some group or category it's easy for us to reject or support; and have some real conversations about the problems that exist in our country and the vastly different ways people seek to right them. I feel like that provides respect for everyone and a real, hopeful path forward.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

Turkey, Communion, and Jesse Eisenberg

Towards the end of last week, I read the comedic anthology Bream Gives Me Hiccups, by actor, Jesse Eisenberg. It's a quirky, intelligent book that mostly plays into my sense of humor.

The first third of the book is a series of essays wherein a 9 year old reviews the NYC restaurants his mom drags him to so his Dad will have to pay (as part of the divorce settlement). As the section continues, the boy begins to review every meal he has, including Thanksgiving with the militant vegans next door. Part of this review is him pondering what a turkey would think about people eating it and especially what the turkey would think about people focusing a holiday on the act of eating it.

Because I'm a theology nerd, this got me thinking about communion. It's essentially a celebratory meal with (depending on your level of adherence to classic Catholic doctrine) involves the eating of a person (a no longer dead person, mind you) as the center piece. Unlike Jesse Eisenberg's hypothetical turkey, Jesus is (allegedly) capable of contemplating you eating him (or in memory of him*).

I feel like Jesus would care a lot less about us taking communion. I'm not saying he would be upset with how prominent we've made it - although I've always been intrigued by the argument (which Derek Davis once presented to me, although I have no idea whether this is just an idea he's was aware of or an idea he holds or even if he did hold and no longer does - that conversation is now a decade old) that Jesus only ever intended the Lord's Supper to be an annual add-on to the Passover Seder, important, but not necessarily pivotal - just that the meal itself should be a sort of reminder that we're supposed to actually live out the things it's designed to symbolize.

If the only thing we're doing in imitation and remembrance of Christ is dipping some bread in some wine, then we're probably missing the point. so in short, perhaps Jesus would say, "yeah, you've got this whole celebration set up around a meal I'm the main course for - great - just don't forget all the other stuff.

And that brings me right back to the turkey at Thanksgiving. We don't eat meat in our house, but I don't object to the eating of meat. I have problems with the way most of our meat is raised and killed, but the meat itself is not an issue with me.** Specifically, in this scenario Eisenberg created, I'm not sure an animal would object to being eaten, especially if it was (humanely) raised for food or killed to keep the overall wild population healthy (although, I suppose, this assumes hypothetical thinking animals would be more rational than the actual thinking animals alive today).*** Again, a scenario in which the meal itself means less than everything leading up to and following from it.

So this is a good example of what my brain is thinking about when you find me staring off into space when I should be paying attention to the party I'm at or the conversation I'm having with you. I do apologize for being rude, but not for having this messed up brain; I kind of like that part.

Toodle-oo.

*Which is, when you think about it, an odd thing to say about a person you believe to be no longer dead.

**Scripturally it's pretty plain to see that God never intended humans to be carnivores - meat is conspicuously absent from the list of foods given by God in Genesis 1; however, I tend to align with the great hebrew scholar Terence Fretheim who says that humans eating meat has become part of creation through human participation in ongoing creation, especially with the advent of domesticated animals, whose major purpose is to supply food for humans.

***I always struggle with that last part. I want to say that a properly managed world shouldn't have the need for culling by humans because the rest of things are in balance. At the same time, though, it feels like that balance would be impossible without predators roaming populated areas to manage the prey who also live there. So, on the one hand we've royally messed up the eco-system by removing dangerous predators from our neighborhoods, but on the other hand, I'm really, really, really glad I don't have to worry about my four year old being dragged off by a mountain lion when I send her out to play in the back yard - even if the existence of that fear would probably mean a world with greater moral integrity.

The first third of the book is a series of essays wherein a 9 year old reviews the NYC restaurants his mom drags him to so his Dad will have to pay (as part of the divorce settlement). As the section continues, the boy begins to review every meal he has, including Thanksgiving with the militant vegans next door. Part of this review is him pondering what a turkey would think about people eating it and especially what the turkey would think about people focusing a holiday on the act of eating it.

Because I'm a theology nerd, this got me thinking about communion. It's essentially a celebratory meal with (depending on your level of adherence to classic Catholic doctrine) involves the eating of a person (a no longer dead person, mind you) as the center piece. Unlike Jesse Eisenberg's hypothetical turkey, Jesus is (allegedly) capable of contemplating you eating him (or in memory of him*).

I feel like Jesus would care a lot less about us taking communion. I'm not saying he would be upset with how prominent we've made it - although I've always been intrigued by the argument (which Derek Davis once presented to me, although I have no idea whether this is just an idea he's was aware of or an idea he holds or even if he did hold and no longer does - that conversation is now a decade old) that Jesus only ever intended the Lord's Supper to be an annual add-on to the Passover Seder, important, but not necessarily pivotal - just that the meal itself should be a sort of reminder that we're supposed to actually live out the things it's designed to symbolize.

If the only thing we're doing in imitation and remembrance of Christ is dipping some bread in some wine, then we're probably missing the point. so in short, perhaps Jesus would say, "yeah, you've got this whole celebration set up around a meal I'm the main course for - great - just don't forget all the other stuff.

And that brings me right back to the turkey at Thanksgiving. We don't eat meat in our house, but I don't object to the eating of meat. I have problems with the way most of our meat is raised and killed, but the meat itself is not an issue with me.** Specifically, in this scenario Eisenberg created, I'm not sure an animal would object to being eaten, especially if it was (humanely) raised for food or killed to keep the overall wild population healthy (although, I suppose, this assumes hypothetical thinking animals would be more rational than the actual thinking animals alive today).*** Again, a scenario in which the meal itself means less than everything leading up to and following from it.

So this is a good example of what my brain is thinking about when you find me staring off into space when I should be paying attention to the party I'm at or the conversation I'm having with you. I do apologize for being rude, but not for having this messed up brain; I kind of like that part.

Toodle-oo.

*Which is, when you think about it, an odd thing to say about a person you believe to be no longer dead.

**Scripturally it's pretty plain to see that God never intended humans to be carnivores - meat is conspicuously absent from the list of foods given by God in Genesis 1; however, I tend to align with the great hebrew scholar Terence Fretheim who says that humans eating meat has become part of creation through human participation in ongoing creation, especially with the advent of domesticated animals, whose major purpose is to supply food for humans.

***I always struggle with that last part. I want to say that a properly managed world shouldn't have the need for culling by humans because the rest of things are in balance. At the same time, though, it feels like that balance would be impossible without predators roaming populated areas to manage the prey who also live there. So, on the one hand we've royally messed up the eco-system by removing dangerous predators from our neighborhoods, but on the other hand, I'm really, really, really glad I don't have to worry about my four year old being dragged off by a mountain lion when I send her out to play in the back yard - even if the existence of that fear would probably mean a world with greater moral integrity.

Labels:

bream gives me hiccups,

communion,

derek davis,

hunting,

jesse eisenberg,

Jesus,

life,

meat,

mountain lions,

practice,

scripture,

terence fretheim,

Thanksgiving,

theology,

turkey,

vegan,

vegetarian

Thursday, August 18, 2016

Lochte and Perception

Yes, Ryan Lochte lied to get himself out of a difficult situation and the lie (predictably) ended up getting him in worse trouble - also he'll probably have to pay his friend back $11,000, which will be tough when he loses most of his sponsorship money. That sucks and its dishonorable, but Ryan Lochte is really just the next in a long line of scapegoats created for the problems in Brazil.

I'm no expert on Brazilian affairs, but this really isn't about Brazil - every community and culture create their own scapegoats to avoid dealing with real, entrenched problems (if you're looking for an easy example: the US scapegoats party culture as a way of avoiding our dysfunctional attitudes towards drugs, alcohol, and sex).

In reality, Rio isn't a very safe place. The government had to take extraordinary measures just to bring their security up to a minimum acceptable level for an international athletic competition. They mobilized reserve military officers, cleaned out favellas, and basically cordoned off entire neighborhoods to give the Olympics clear access to the parts of the city they needed access to. It was like they created a city within the city (or, more correctly, four small cities with dedicated road and rail ways in between) to ensure that the global generalization of Rio as crime-ridden wouldn't be the story of the Olympics.

That is part of the reason why this Lochte lie is so infuriating to them - here's an actual made-up story that reinforces the stereotype. People deserve to be mad. That sucks, especially after all the work they went to. But it's a bit hypocritical to say Lochte is creating a false narrative about the safety of the games when really he's just creating a false perception about the already false narrative Brazil itself took to present a different face to the world.

If Rio was as safe a place as we're led to believe, none of those pre-Games precautions would've been necessary. Lochte, as wrong as he most certainly was/is, just presents a convenient scapegoat to avoid the larger, uncomfortable truth. The entitled American. The beauty of a scapegoat is that they're rarely 100% innocent, which makes it easier to pin all the blame on them. Before Lochte, in Brazil it was the favellas - the famous Rio slums - thus justifying the displacement of poor communities. Prior to that, the ongoing class tussle over who's more responsible for the spiraling economic inequality.

We saw the same thing with the World Cup in Brazil just two years ago - and those street protests led to huge corruption probes and the impeachment of the President. I found it ironic that an official spokeswoman this week said in a radio interview that the World Cup went off without any incidents - but I remember reading multiple first-person accounts from journalists that involved sprinting down closed streets under armed police protection while angry crowds launched homemade Molotov Cocktails at the special protection zones set up for World Cup participants, journalists, and fans.

It's a "king has no clothes" scenario - and the scapegoat provides the out.

Yes, four drunk swimmers messed up a gas station, tried to buy their way out of it and told a lie assuming their credibility would hold up and Rio was too poor to have decent video surveillance? That's not good, but it's not the makings of an international incident - as the Brazilian government and the US media would have us believe. It's a diversion - and not an unfamiliar one.

Our real problems are buried deep, and addressing them requires facing and enduring pain we'd rather just avoid. Putting all that drama, junk, and responsibility on someone else seems like a great deal. They become the villain, we excise our demons; life goes on.

Of course it doesn't, though. Because the pressure will just build up again and we'll need another outlet. One scapegoat can only survive so long, then we'll go looking for more. And more. It's as if we're addicted to denial and, at some point, there's not even enough left to get us high.

In the end, the real mistake is pinning fault on one person or a group instead of people taking a collective responsibility for the problems we've collectively created. I still use, "we," even though I'm not Brazilian and have never been there, simply because there is no limit to the scapegoating. It would be easy to oversimplify the other way - say "Rio is unsafe," and move along. I made a stupid, snide comment on Facebook about the whole thing the other day that played right into the danger stereotype in a way that just scapegoated Brazil rather than addressing the issue (part of the reason why I'm writing this longer piece - I need atonement). It's the same problem created by making Lochte just another spoiled athlete or boorish American athlete; we avoid claiming responsibility for our own severe lack of global understanding, empathy, and cameraderie, as well as our severe wealth of arrogance.

Blame someone else, I can pretend it's not my problem. I'm not an alcoholic because that other guy beats his wife every time he comes home drunk. We make "him" the villain to keep fooling ourselves into thinking we're not so bad. It's all about perspective - are we looking at the world in the easiest way for us, in ways that make us comfortable - or are we genuinely interested in tackling the real, entrenched problems that tend to bring us (all of us) down?

Gosh, personally, I'm just not sure - but I think the best course of action is to take responsibility first and dole it out later.

I'm no expert on Brazilian affairs, but this really isn't about Brazil - every community and culture create their own scapegoats to avoid dealing with real, entrenched problems (if you're looking for an easy example: the US scapegoats party culture as a way of avoiding our dysfunctional attitudes towards drugs, alcohol, and sex).

In reality, Rio isn't a very safe place. The government had to take extraordinary measures just to bring their security up to a minimum acceptable level for an international athletic competition. They mobilized reserve military officers, cleaned out favellas, and basically cordoned off entire neighborhoods to give the Olympics clear access to the parts of the city they needed access to. It was like they created a city within the city (or, more correctly, four small cities with dedicated road and rail ways in between) to ensure that the global generalization of Rio as crime-ridden wouldn't be the story of the Olympics.

That is part of the reason why this Lochte lie is so infuriating to them - here's an actual made-up story that reinforces the stereotype. People deserve to be mad. That sucks, especially after all the work they went to. But it's a bit hypocritical to say Lochte is creating a false narrative about the safety of the games when really he's just creating a false perception about the already false narrative Brazil itself took to present a different face to the world.

If Rio was as safe a place as we're led to believe, none of those pre-Games precautions would've been necessary. Lochte, as wrong as he most certainly was/is, just presents a convenient scapegoat to avoid the larger, uncomfortable truth. The entitled American. The beauty of a scapegoat is that they're rarely 100% innocent, which makes it easier to pin all the blame on them. Before Lochte, in Brazil it was the favellas - the famous Rio slums - thus justifying the displacement of poor communities. Prior to that, the ongoing class tussle over who's more responsible for the spiraling economic inequality.

We saw the same thing with the World Cup in Brazil just two years ago - and those street protests led to huge corruption probes and the impeachment of the President. I found it ironic that an official spokeswoman this week said in a radio interview that the World Cup went off without any incidents - but I remember reading multiple first-person accounts from journalists that involved sprinting down closed streets under armed police protection while angry crowds launched homemade Molotov Cocktails at the special protection zones set up for World Cup participants, journalists, and fans.

It's a "king has no clothes" scenario - and the scapegoat provides the out.

Yes, four drunk swimmers messed up a gas station, tried to buy their way out of it and told a lie assuming their credibility would hold up and Rio was too poor to have decent video surveillance? That's not good, but it's not the makings of an international incident - as the Brazilian government and the US media would have us believe. It's a diversion - and not an unfamiliar one.

Our real problems are buried deep, and addressing them requires facing and enduring pain we'd rather just avoid. Putting all that drama, junk, and responsibility on someone else seems like a great deal. They become the villain, we excise our demons; life goes on.

Of course it doesn't, though. Because the pressure will just build up again and we'll need another outlet. One scapegoat can only survive so long, then we'll go looking for more. And more. It's as if we're addicted to denial and, at some point, there's not even enough left to get us high.

In the end, the real mistake is pinning fault on one person or a group instead of people taking a collective responsibility for the problems we've collectively created. I still use, "we," even though I'm not Brazilian and have never been there, simply because there is no limit to the scapegoating. It would be easy to oversimplify the other way - say "Rio is unsafe," and move along. I made a stupid, snide comment on Facebook about the whole thing the other day that played right into the danger stereotype in a way that just scapegoated Brazil rather than addressing the issue (part of the reason why I'm writing this longer piece - I need atonement). It's the same problem created by making Lochte just another spoiled athlete or boorish American athlete; we avoid claiming responsibility for our own severe lack of global understanding, empathy, and cameraderie, as well as our severe wealth of arrogance.

Blame someone else, I can pretend it's not my problem. I'm not an alcoholic because that other guy beats his wife every time he comes home drunk. We make "him" the villain to keep fooling ourselves into thinking we're not so bad. It's all about perspective - are we looking at the world in the easiest way for us, in ways that make us comfortable - or are we genuinely interested in tackling the real, entrenched problems that tend to bring us (all of us) down?

Gosh, personally, I'm just not sure - but I think the best course of action is to take responsibility first and dole it out later.

Labels:

brazil,

olympics,

perception,

perspective,

rio,

ryan lochte,

scapegoat,

villains,

world cup

Thursday, August 11, 2016

Athletics and Ambiguity

So, the Olympics have gone pretty well so far - at least from the American perspective. The US is way out in front in the medal count and the swimming - the #1 feature of prime time coverage in the first week - has been an unquestionable success. I'm glad to see the narrative has been largely on great feats of athletics and not on the drama NBC so often likes to imbue these events with.

There was a little trouble with Lily King and her comments on doping becoming a new Cold War, USA vs Russia thing, but those blew over pretty quickly. I'm glad a young athlete has the courage to speak out and make a statement - it's exactly the kind of thing we want a 19 year old to do. I was a little troubled, though, that nowhere, does it seem, is NBC going to address the complexity of issues that come along with this Russian doping problem.

It'll likely come up again as Track and Field takes off in the second week, since Russia's entire track team was banned from the games. I'll say up front, I was and remain supportive of the move to ban all Russian athletes from the Games. Yes, it is an unfair punishment for athletes that were never involved in doping, but really Russia was the one making it unfair for them - and bland punishments like this one do nothing to discourage the same kind of thing going forward. The IOC left it up to individual sporting federations to rule on Russian participation. Most sports, like swimming, reviewed athletes on a case by case basis, with some pretty nebulous criteria, before allowing participation. The ambiguity is troubling.

At the same time, the ambiguity of a state-sponsored doping program is troubling, too. Julia Efimova, the Russian swimmer King picked her verbal fight with has been banned twice for doping offenses. King made the case that no one (including US track star, Justin Gatlin) previously caught doping should be able to compete ever.

It's a harsh, but certainly understandable position. Especially in a modern athletic environment where most legitimate supplements have third-party testing and verification so those "it must have been contaminated" excuses we've heard from baseball players over the years don't hold weight anymore. At the same time, a situation like Russia is complicated. Again, King is 19 - she's supposed to think in black & white; I'm just glad she feels bold enough to speak. She's also spent her life in the US athletic environment, which is the most democratic in the world. Usain Bolt was injured for the Jamaican Olympic trials, but they still put him on the team - US athletes never get that special treatment, even the biggest stars; you have to perform to earn your spot.

It's not the same in other place. Russia, especially, as we've seen, has a large state presence in sport. Athletes are chosen, sometimes, for political reasons over performance. In the instance of a state-sponsored program like this, the ultimatum of "take this supplement or never compete for Russia again," isn't all that far-fetched. Efimova and any of the other Russian athletes involved didn't exactly have the clear cut choice PEDs are so often made out to be.

We laugh about the long-standing world records set in the late 70's and 80's by eastern bloc athletes - especially female track athletes and how they're so nearly impossible to break because of the state sponsored doping programs at the time. The athletes become the villains in those stories like Drago in Rocky when more than likely they were taken from their families at a young age, when athletic aptitude was first spotted, and had their lives run for them as they rose to prominence. I'm not saying that Putin was holding a gun to someone's head and forcing a strange powder into their smoothie, but it's also not like an after-school special. Things are complicated.

You can add to that the very real belief by not a few people that everyone is still doping, especially track sprinters, and when coupled with national pressure, there's very little incentive not to go along.

You can make the ambiguity argument for Gatlin as well. He got caught twice, served a long suspension, but seems genuinely the victim of ignorance and bad coaching. His offenses were at the height of widespread doping and well before athletes had real tools for taking responsibility. That doesn't mean he's clean, though - he may simply be doping because it's the only way for him to win and make a living. We just don't know. No one thought cyclists were doping either, right up until they found out literally every single one of them was doing it. It's this ambiguity that makes modern athletics so beautiful and terrifying.

NPR had an author on this week, talking about how performance enhancing drugs were considered a normal and necessary part of professional athletics right up into the 1960's. To do amazing things, people expected athletes to use as much science as was available - and trusted them to judge for themselves how they treated their own bodies. Yes, this was before TV and money was really involved, and it was prior to understanding the long-term effects of these substances - but that only adds to the ambiguity, it doesn't lessen anything.

On top of all that, you have the delineation of what's ok and what's not. Laser eye surgery can correct vision beyond "perfect," improving sight beyond what a "normal" person would have. Is that an unfair advantage? The same might go for advanced blood transfusion techniques - which some sports ban and others allow. What about gene therapy and medical science coming down the road?

It's never, ever going to be cut and dry. Shoot, the boxing, rugby, and the NFL have to worry about whether playing the sport itself is too great a danger to athletes, let alone any of the other additions or performance enhancers that might be involved. We're all going to draw a line somewhere - and I want Lily King to keep doing it and talking about it - but we need to be very careful about making heroes and villains out of this whole thing. We've got to have rules - I think Russia got off too easy in this whole mess. At the same time, we have to remember: in sport, we want things to be simple and definitive, it just never is.

Athletics and ambiguity always go hand in hand.

There was a little trouble with Lily King and her comments on doping becoming a new Cold War, USA vs Russia thing, but those blew over pretty quickly. I'm glad a young athlete has the courage to speak out and make a statement - it's exactly the kind of thing we want a 19 year old to do. I was a little troubled, though, that nowhere, does it seem, is NBC going to address the complexity of issues that come along with this Russian doping problem.

It'll likely come up again as Track and Field takes off in the second week, since Russia's entire track team was banned from the games. I'll say up front, I was and remain supportive of the move to ban all Russian athletes from the Games. Yes, it is an unfair punishment for athletes that were never involved in doping, but really Russia was the one making it unfair for them - and bland punishments like this one do nothing to discourage the same kind of thing going forward. The IOC left it up to individual sporting federations to rule on Russian participation. Most sports, like swimming, reviewed athletes on a case by case basis, with some pretty nebulous criteria, before allowing participation. The ambiguity is troubling.

At the same time, the ambiguity of a state-sponsored doping program is troubling, too. Julia Efimova, the Russian swimmer King picked her verbal fight with has been banned twice for doping offenses. King made the case that no one (including US track star, Justin Gatlin) previously caught doping should be able to compete ever.

It's a harsh, but certainly understandable position. Especially in a modern athletic environment where most legitimate supplements have third-party testing and verification so those "it must have been contaminated" excuses we've heard from baseball players over the years don't hold weight anymore. At the same time, a situation like Russia is complicated. Again, King is 19 - she's supposed to think in black & white; I'm just glad she feels bold enough to speak. She's also spent her life in the US athletic environment, which is the most democratic in the world. Usain Bolt was injured for the Jamaican Olympic trials, but they still put him on the team - US athletes never get that special treatment, even the biggest stars; you have to perform to earn your spot.

It's not the same in other place. Russia, especially, as we've seen, has a large state presence in sport. Athletes are chosen, sometimes, for political reasons over performance. In the instance of a state-sponsored program like this, the ultimatum of "take this supplement or never compete for Russia again," isn't all that far-fetched. Efimova and any of the other Russian athletes involved didn't exactly have the clear cut choice PEDs are so often made out to be.

We laugh about the long-standing world records set in the late 70's and 80's by eastern bloc athletes - especially female track athletes and how they're so nearly impossible to break because of the state sponsored doping programs at the time. The athletes become the villains in those stories like Drago in Rocky when more than likely they were taken from their families at a young age, when athletic aptitude was first spotted, and had their lives run for them as they rose to prominence. I'm not saying that Putin was holding a gun to someone's head and forcing a strange powder into their smoothie, but it's also not like an after-school special. Things are complicated.

You can add to that the very real belief by not a few people that everyone is still doping, especially track sprinters, and when coupled with national pressure, there's very little incentive not to go along.

You can make the ambiguity argument for Gatlin as well. He got caught twice, served a long suspension, but seems genuinely the victim of ignorance and bad coaching. His offenses were at the height of widespread doping and well before athletes had real tools for taking responsibility. That doesn't mean he's clean, though - he may simply be doping because it's the only way for him to win and make a living. We just don't know. No one thought cyclists were doping either, right up until they found out literally every single one of them was doing it. It's this ambiguity that makes modern athletics so beautiful and terrifying.

NPR had an author on this week, talking about how performance enhancing drugs were considered a normal and necessary part of professional athletics right up into the 1960's. To do amazing things, people expected athletes to use as much science as was available - and trusted them to judge for themselves how they treated their own bodies. Yes, this was before TV and money was really involved, and it was prior to understanding the long-term effects of these substances - but that only adds to the ambiguity, it doesn't lessen anything.

On top of all that, you have the delineation of what's ok and what's not. Laser eye surgery can correct vision beyond "perfect," improving sight beyond what a "normal" person would have. Is that an unfair advantage? The same might go for advanced blood transfusion techniques - which some sports ban and others allow. What about gene therapy and medical science coming down the road?

It's never, ever going to be cut and dry. Shoot, the boxing, rugby, and the NFL have to worry about whether playing the sport itself is too great a danger to athletes, let alone any of the other additions or performance enhancers that might be involved. We're all going to draw a line somewhere - and I want Lily King to keep doing it and talking about it - but we need to be very careful about making heroes and villains out of this whole thing. We've got to have rules - I think Russia got off too easy in this whole mess. At the same time, we have to remember: in sport, we want things to be simple and definitive, it just never is.

Athletics and ambiguity always go hand in hand.

Tuesday, August 09, 2016

Joy vs Pleasure

So, the dictionary definition of joy is literally pleasure, and vice versa. Websters considers them interchangeable. So maybe I need to do some other clarification when I attempt to differentiate between the two. In actuality, though, it's the perfect example of what I'm trying to say: in our modern world, we really have no difference between joy and pleasure.

It might be better termed Deep Satisfaction vs Deep Happiness. I think there is a difference. Pleasure is fleeting; it's focused on feelings and emotion, while joy is something deeper; it's more about a state of being. Pleasure is something you feel; joy is something you embody.

Again, the dictionary likely disagrees - then this just becomes a big game of semantics - but lets see through the technicalities to the core concept of these differences. Joy and pleasure are both unique and deeply personal. When it comes to pleasure, we don't call them fetishes for nothing, right?

When I think of joy, the first memory that comes to mind is sitting in our rental Kia at Whitney Portal at 3 in the afternoon. A friend and I had just spent the previous 14 hours hiking to the top of Mt. Whitney and back down - about 21 miles in total. I'd just taken my boots off. My feet were literally throbbing with a dull, consistent pain; every one of my leg muscles was aching. There was nothing pleasurable about that moment, but I can't recall a deeper experience of pure joy in my entire life.

Now sometimes these two things are quite connected. I'm not sure I can fully comprehend even now the experience of holding my newborn daughter in my arms in her first moments of life, but I'm almost positive both pleasure and joy were mixed up in it. But what I've been thinking about a bit lately is how much we've (society in general? westerners? whoever) come to expect joy and pleasure to be one and the same. We expect all of our best moments to be happy moments. We're constantly seeking pleasure when what we really long for is a deep, abiding joy.

Joy isn't always pleasure - and we've completely forgotten about that.

Joy, I believe, comes with a discovery, even just a glimpse, of what it means to discover real purpose. Human beings were certainly made to be happy, but human beings were certainly not made just to be happy. I'd argue our purpose is to suffer together - if we're talking about the dictionary: we're made for compassion. Passion comes from the latin for struggle - we are made to be co-strugglers. I believe we experience joy when we experience the realities of life (both pleasurable and otherwise); and I think we experience this joy most deeply when we do so in connection to someone else - even if that other is creation itself.

For me, it's a hike through the woods or the indescribably joyful feeling of insignificance I experience looking out over an expansive mountain range. For me, this is a broad brush of humanity barreling down at me from great distance. It helps me appreciate the struggle.

We find no pleasure in a loved one who suffers tragedy, but we do experience joy in walking through such tragedy with them. The struggles of life are not things we wish on anyone, but we also consider life (and its necessary struggles) an almost priceless, beautiful gift. Why? I think the answer is joy.

We're part of a world that speaks only to pleasure - finding happiness is the solution to all your problems and the fulfillment of your purpose. We seek blindly after pleasure and when we find it empty, we assume we've not yet found the right pleasure and we move on. It's an addiction to happiness and an aversion to pain. I don't think either of these characterize life.

As a Christian, there's common belief in an eternity with no sorrow or pain - but those are so often used as synonymns, the same way joy and pleasure so often are. Just like joy and pleasure are really two different concepts, so too are sorrow and pain. Sorrow is the opposite of joy - a lack of purpose, self-worth, dignity, meaning; I fully believe these things can and will be eradicated by love. That's the hope I profess. I'm less confident, though, that pain is fleeting or ultimately doomed.

There is just as much chance for joy in pain as there is in pleasure - at least my experiences tell me that's true - in the same way as there's just as much room for sorrow in pleasure as there is in pain. These things are not necessarily linked. Think about it - a relationship without misunderstanding or miscommunication is no relationship at all. The very value of any relationship is the unpredictability, the otherness of the other. If we always said the right thing, we'd quickly grow tired of each other. Our ability to surprise, even after ten, twenty, fifty, a hundred years together is what provides the great joy that comes from relationships. If the cost of this unpredictable joy is occasional pain, I think it's worth every penny.

Again, this pain is not confused with sorrow, specifically the sorrow that comes from intentional harm, hurt, and insult. Relationships have that, too - at least for the time being. Pain comes from the same joyful unpredictability; sorrow comes from selfishness.

In the end, it may be just that simple. We can experience joy when we're living purely for the benefit of others - whether it's enjoying a brisk evening walk among the trees or sitting by the bedside of a cancer-ridden spouse, joy can persist in the midst of both pleasure and pain. Pleasure is certainly not a bad thing, but pursuit of our own pleasure as an end in itself will bring nothing but sorrow. Pursuit of pleasure for another might bring happiness for ourselves too, but much more than that, it will bring a deep and abiding joy that reveals all the best of what life has to offer and the very purpose for our existence.

Let's not let the dictionary have the final word here.

It might be better termed Deep Satisfaction vs Deep Happiness. I think there is a difference. Pleasure is fleeting; it's focused on feelings and emotion, while joy is something deeper; it's more about a state of being. Pleasure is something you feel; joy is something you embody.

Again, the dictionary likely disagrees - then this just becomes a big game of semantics - but lets see through the technicalities to the core concept of these differences. Joy and pleasure are both unique and deeply personal. When it comes to pleasure, we don't call them fetishes for nothing, right?

When I think of joy, the first memory that comes to mind is sitting in our rental Kia at Whitney Portal at 3 in the afternoon. A friend and I had just spent the previous 14 hours hiking to the top of Mt. Whitney and back down - about 21 miles in total. I'd just taken my boots off. My feet were literally throbbing with a dull, consistent pain; every one of my leg muscles was aching. There was nothing pleasurable about that moment, but I can't recall a deeper experience of pure joy in my entire life.

Now sometimes these two things are quite connected. I'm not sure I can fully comprehend even now the experience of holding my newborn daughter in my arms in her first moments of life, but I'm almost positive both pleasure and joy were mixed up in it. But what I've been thinking about a bit lately is how much we've (society in general? westerners? whoever) come to expect joy and pleasure to be one and the same. We expect all of our best moments to be happy moments. We're constantly seeking pleasure when what we really long for is a deep, abiding joy.

Joy isn't always pleasure - and we've completely forgotten about that.

Joy, I believe, comes with a discovery, even just a glimpse, of what it means to discover real purpose. Human beings were certainly made to be happy, but human beings were certainly not made just to be happy. I'd argue our purpose is to suffer together - if we're talking about the dictionary: we're made for compassion. Passion comes from the latin for struggle - we are made to be co-strugglers. I believe we experience joy when we experience the realities of life (both pleasurable and otherwise); and I think we experience this joy most deeply when we do so in connection to someone else - even if that other is creation itself.

For me, it's a hike through the woods or the indescribably joyful feeling of insignificance I experience looking out over an expansive mountain range. For me, this is a broad brush of humanity barreling down at me from great distance. It helps me appreciate the struggle.

We find no pleasure in a loved one who suffers tragedy, but we do experience joy in walking through such tragedy with them. The struggles of life are not things we wish on anyone, but we also consider life (and its necessary struggles) an almost priceless, beautiful gift. Why? I think the answer is joy.

We're part of a world that speaks only to pleasure - finding happiness is the solution to all your problems and the fulfillment of your purpose. We seek blindly after pleasure and when we find it empty, we assume we've not yet found the right pleasure and we move on. It's an addiction to happiness and an aversion to pain. I don't think either of these characterize life.

As a Christian, there's common belief in an eternity with no sorrow or pain - but those are so often used as synonymns, the same way joy and pleasure so often are. Just like joy and pleasure are really two different concepts, so too are sorrow and pain. Sorrow is the opposite of joy - a lack of purpose, self-worth, dignity, meaning; I fully believe these things can and will be eradicated by love. That's the hope I profess. I'm less confident, though, that pain is fleeting or ultimately doomed.

There is just as much chance for joy in pain as there is in pleasure - at least my experiences tell me that's true - in the same way as there's just as much room for sorrow in pleasure as there is in pain. These things are not necessarily linked. Think about it - a relationship without misunderstanding or miscommunication is no relationship at all. The very value of any relationship is the unpredictability, the otherness of the other. If we always said the right thing, we'd quickly grow tired of each other. Our ability to surprise, even after ten, twenty, fifty, a hundred years together is what provides the great joy that comes from relationships. If the cost of this unpredictable joy is occasional pain, I think it's worth every penny.

Again, this pain is not confused with sorrow, specifically the sorrow that comes from intentional harm, hurt, and insult. Relationships have that, too - at least for the time being. Pain comes from the same joyful unpredictability; sorrow comes from selfishness.

In the end, it may be just that simple. We can experience joy when we're living purely for the benefit of others - whether it's enjoying a brisk evening walk among the trees or sitting by the bedside of a cancer-ridden spouse, joy can persist in the midst of both pleasure and pain. Pleasure is certainly not a bad thing, but pursuit of our own pleasure as an end in itself will bring nothing but sorrow. Pursuit of pleasure for another might bring happiness for ourselves too, but much more than that, it will bring a deep and abiding joy that reveals all the best of what life has to offer and the very purpose for our existence.

Let's not let the dictionary have the final word here.

Thursday, August 04, 2016

Punishment vs Consequence

I got to spend a week at camp with 230-some teenagers (which is part of the reason these posts are late this week). There was some good time for reflection, renewal, and thinking. One of the things that struck me most profoundly (I guess because I'm now old and my memory fades) was the reminder of just how tough it is to be figuring out how the world works. Navigating adolescence and the search for understanding is tough, even with a supportive environment where people love and care for you.

It's not just teenagers, though - I mean it's a search everyone is on for their entire lives. But this week it just kind of struck me how important it is for us (all of us - parents, children, adults, teenagers, humans) to understand punishment and consequences. I feel like I've written about this before, how punishment is really a way for authority figures to display grace. Punishment most often occurs as a means of avoiding the consequences of some action. Someone driving drunk is punished as a way of bringing the very real consequences of that action into view. A person who drives drunk and kills someone with their car experiences the consequence. Even in that scenario, there's still a punishment. Typically the consequence of killing someone is that we die ourselves. Society, in general, cares enough about life to not repay death with death. Regardless the consequences are serious.

As a teenager, punishment feels like torture. There's no way around it. It feels that way on purpose, because if we understood consequences deeply enough, punishment wouldn't be necessary. Now not every authority is perfect and punishment does sometimes end up being punitive. That's regrettable. These errors in punishment, though, shape how we view the world, especially if take a theistic view of things.

It's real easy to look at the consequences of our actions as divine reward or punishment. This is likely more true in places most guarded from real consequences. In the modern US we shelter our kids, our families, large parts of our society from any real dangers. It is few and far between who suffer real consequences from our poor choices - and we tend to ignore, hide, or marginalize those who do suffer. So much of it is in secret. Thus, we're really living in a world of punishment - actions intended to teach us lessons about consequences, but facing few real, actual consequences.

This means we expect everything that happens to us to be someone else's choice. Kids are far more worried about what their parents might do if they're caught drinking on a Friday night than the hangover they'll have the next day (and even less concerned about cirrhosis in the future). Punishment is just our major frame of reference.

We project this on God.

My mom is a drug addict and abandoned me when I was a baby to be raised in marginally safer foster homes the rest of my life. That is really a number of tragic consequences to poor choices made by many people. But it's really easy to see it as divine punishment for something we did or for just not being a good enough person, punishment for some inherent failure.

I suppose it's inherently human to think this way. Our first inclination of the world is that someone somewhere is pulling the strings on everything. It's an underlying cultural assumption even into the present day. It's one of the reasons scientists get so fed up - not just that some religious people continue to propagate this notion, but that so many people believe it even without strong faith commitments. In this worldview, karma makes sense. The world somehow rewards and punishes people - and often in unjust, arbitrary ways.

I don't think the world really works like that. I make that statement as a faith claim, as someone who's spent a lot of time studying the Bible and theology - and the world around me. Science makes that claim, too - action and reaction, cause and effect. The things that happen to us are not rewards and punishments, they are consequences. They are the result of action, conscious or otherwise.

As a faith commitment, I believe in a God that suffers with humanity - a God who does not reward and punish, but who walks with us through life, enduring consequences as we endure them. God celebrates and mourns right alongside us. It is this loving co-suffering that is exemplified in Jesus and to which each of us are challenged to. I believe this is the way to live well in the world.

This is the difference between grace and torture.

If we see God as punitive, we can only see life as torture. It's pain, divinely inflicted pain, for no discernible reason other than existence. It's depressing and it's no wonder people flounder around in search of meaning when life looks like that. Instead, we should see (or try to learn to see) God's presence in the midst of pain as profound grace. God, and those people around you who represent God in your life, walking with you through the inevitable ups and downs (and the far more serious celebrations and crises) that life brings, are hope in the midst of despair.

This world is not about rewards and punishments - at least not deep down. It is about riding the wave of consequences and, if you cling to some measure of faith, trusting that our loving co-suffering can actually make a difference down the line. I believe that love changes things, but we have to see grace and love and peace around us to ever see this change.

It starts, at least in part, with how we see God present in the midst of tragedy.

It's not just teenagers, though - I mean it's a search everyone is on for their entire lives. But this week it just kind of struck me how important it is for us (all of us - parents, children, adults, teenagers, humans) to understand punishment and consequences. I feel like I've written about this before, how punishment is really a way for authority figures to display grace. Punishment most often occurs as a means of avoiding the consequences of some action. Someone driving drunk is punished as a way of bringing the very real consequences of that action into view. A person who drives drunk and kills someone with their car experiences the consequence. Even in that scenario, there's still a punishment. Typically the consequence of killing someone is that we die ourselves. Society, in general, cares enough about life to not repay death with death. Regardless the consequences are serious.

As a teenager, punishment feels like torture. There's no way around it. It feels that way on purpose, because if we understood consequences deeply enough, punishment wouldn't be necessary. Now not every authority is perfect and punishment does sometimes end up being punitive. That's regrettable. These errors in punishment, though, shape how we view the world, especially if take a theistic view of things.

It's real easy to look at the consequences of our actions as divine reward or punishment. This is likely more true in places most guarded from real consequences. In the modern US we shelter our kids, our families, large parts of our society from any real dangers. It is few and far between who suffer real consequences from our poor choices - and we tend to ignore, hide, or marginalize those who do suffer. So much of it is in secret. Thus, we're really living in a world of punishment - actions intended to teach us lessons about consequences, but facing few real, actual consequences.

This means we expect everything that happens to us to be someone else's choice. Kids are far more worried about what their parents might do if they're caught drinking on a Friday night than the hangover they'll have the next day (and even less concerned about cirrhosis in the future). Punishment is just our major frame of reference.

We project this on God.

My mom is a drug addict and abandoned me when I was a baby to be raised in marginally safer foster homes the rest of my life. That is really a number of tragic consequences to poor choices made by many people. But it's really easy to see it as divine punishment for something we did or for just not being a good enough person, punishment for some inherent failure.

I suppose it's inherently human to think this way. Our first inclination of the world is that someone somewhere is pulling the strings on everything. It's an underlying cultural assumption even into the present day. It's one of the reasons scientists get so fed up - not just that some religious people continue to propagate this notion, but that so many people believe it even without strong faith commitments. In this worldview, karma makes sense. The world somehow rewards and punishes people - and often in unjust, arbitrary ways.

I don't think the world really works like that. I make that statement as a faith claim, as someone who's spent a lot of time studying the Bible and theology - and the world around me. Science makes that claim, too - action and reaction, cause and effect. The things that happen to us are not rewards and punishments, they are consequences. They are the result of action, conscious or otherwise.

As a faith commitment, I believe in a God that suffers with humanity - a God who does not reward and punish, but who walks with us through life, enduring consequences as we endure them. God celebrates and mourns right alongside us. It is this loving co-suffering that is exemplified in Jesus and to which each of us are challenged to. I believe this is the way to live well in the world.

This is the difference between grace and torture.

If we see God as punitive, we can only see life as torture. It's pain, divinely inflicted pain, for no discernible reason other than existence. It's depressing and it's no wonder people flounder around in search of meaning when life looks like that. Instead, we should see (or try to learn to see) God's presence in the midst of pain as profound grace. God, and those people around you who represent God in your life, walking with you through the inevitable ups and downs (and the far more serious celebrations and crises) that life brings, are hope in the midst of despair.

This world is not about rewards and punishments - at least not deep down. It is about riding the wave of consequences and, if you cling to some measure of faith, trusting that our loving co-suffering can actually make a difference down the line. I believe that love changes things, but we have to see grace and love and peace around us to ever see this change.

It starts, at least in part, with how we see God present in the midst of tragedy.

Labels:

consequences,

God,

grace,

humanity,

life,

perspective,

punishment,

science,

torture,

world

Tuesday, August 02, 2016

An Ideological Comparison

I've sat around the last few weeks (in those rare moments I get to sit these days) and really struggled with the tension inherent in my nation's problems. As much as our media has perfected sound-byte wars and click bait headlines and the commodification of "news," complexity persists. There's nothing so simple as it seems.

I've struggled with how to express strong, uncomfortable truths in ways that maintain the dignity of those who are being critiqued. It's a difficult path to tread these days and quite possibly beyond my abilities. I've noticed an interesting parallel, though, that perhaps might give us pause to think about such complexities.

I've not polled anyone; this is purely anecdotal. If you don't have the tendencies I'm referencing here, this post probably isn't for you, feel free to stop reading. But I've noticed that people on the right tend to support police uncritically, while lodging serious complaints against teachers unions as a major issue in education. Similarly, those on the left tend to support teachers uncritically, while lodging serious complaints against the fraternality of police officers as a major impediment to racial and violence issues in society.

The parallels are interesting. These are two professions where the familial ties of union still ring strong across the country. There's a sense of duty and loyalty to those who serve together in the trenches that tends to bring with it a level of grace and forgiveness that's beyond what the general public might bestow.

As a pastor, my ears prick up at the all too common rationalization, "But I'm a good person, so I can let ________________ slide; nobody's perfect." We understand the difficulties we face in life and, rightfully, are gracious with ourselves. When we can so easily put ourselves in someone else's shoes, it's easy for us to give them the same measure of understanding - at least as much as we'd want.

I recognize that police and teachers aren't exactly on the same level; a bad teacher will almost never cost a student their life. At the same time, we put a lot of pressure on them to plug the straining dykes of societal backwash. We sort of expect the police and teachers to solve poverty without many of the resources that are absolutely essential to the job. The best police officer on earth will not prevent crimes or lower the number of criminals - threat of punishment is rarely, if ever, a deterrent (at least on a macro level). The best teacher on earth will not prevent students from missing educational opportunities. There are great stories or police and teachers affecting the lives of individuals in profound ways - and good teachers/police certainly can do so more often than bad ones - but thinking that these professions, even at their best, can tackle the problems society expects them to solve is sort of like asking someone to keep the ground dry in a rainstorm. The very fact that people keep trying is a real testament to the optimism of the human spirit.

Now I could outline a lot of things the police do that really works against their goals, as impossible as they may seem. The same could be said for teachers (as a group, remember, when we personalize these things, make them about that officer I know, that teacher who lives under the same roof, the whole conversation gets pulled out of context). It doesn't take a genius to see that things can and should be done differently. That's what people criticize. We've got neighborhoods out there where kids are more likely to end up in prison than college - that shouldn't necessarily demean that police and teachers who work hard to change the situation, but it's also a pretty strong condemnation of both systems in which they work.

I guess my point is that it's the same story. One gets used as a liberal crusade and the other to bolster conservative ranks. There are lots of kids convinced the cops are out to get them; a lot feel the same way about teachers. On the whole, that notion is silly and paranoid, but not all of those kids are wrong. There's the rub.

When things are broken, it's easier to blame someone else than roll up one's own sleeves. We can conveniently point to the people specifically charged with handling that "problem," and replace them if they fail too badly. But the responsibility we put on people, like police or teachers, is not their responsibility, it's our collective responsibility. There's a lot of good, sincere people attempting to do both of these jobs - just because some of them could be better, the drive and effort shouldn't be demeaned. The tight-knit unions that protect police and teachers don't do a lot to help society at large be sympathetic to the issues they face, but that shouldn't demean sincerity and commitment either.

The reality is that no hero's perfect, but also that no hero should ever be scared of admitting the truth of that statement. It's our responsibility to create the environment where that can happen. I suggest we do a better job of it before we go after "the other guy" or defend our own.

I've struggled with how to express strong, uncomfortable truths in ways that maintain the dignity of those who are being critiqued. It's a difficult path to tread these days and quite possibly beyond my abilities. I've noticed an interesting parallel, though, that perhaps might give us pause to think about such complexities.

I've not polled anyone; this is purely anecdotal. If you don't have the tendencies I'm referencing here, this post probably isn't for you, feel free to stop reading. But I've noticed that people on the right tend to support police uncritically, while lodging serious complaints against teachers unions as a major issue in education. Similarly, those on the left tend to support teachers uncritically, while lodging serious complaints against the fraternality of police officers as a major impediment to racial and violence issues in society.

The parallels are interesting. These are two professions where the familial ties of union still ring strong across the country. There's a sense of duty and loyalty to those who serve together in the trenches that tends to bring with it a level of grace and forgiveness that's beyond what the general public might bestow.

As a pastor, my ears prick up at the all too common rationalization, "But I'm a good person, so I can let ________________ slide; nobody's perfect." We understand the difficulties we face in life and, rightfully, are gracious with ourselves. When we can so easily put ourselves in someone else's shoes, it's easy for us to give them the same measure of understanding - at least as much as we'd want.

I recognize that police and teachers aren't exactly on the same level; a bad teacher will almost never cost a student their life. At the same time, we put a lot of pressure on them to plug the straining dykes of societal backwash. We sort of expect the police and teachers to solve poverty without many of the resources that are absolutely essential to the job. The best police officer on earth will not prevent crimes or lower the number of criminals - threat of punishment is rarely, if ever, a deterrent (at least on a macro level). The best teacher on earth will not prevent students from missing educational opportunities. There are great stories or police and teachers affecting the lives of individuals in profound ways - and good teachers/police certainly can do so more often than bad ones - but thinking that these professions, even at their best, can tackle the problems society expects them to solve is sort of like asking someone to keep the ground dry in a rainstorm. The very fact that people keep trying is a real testament to the optimism of the human spirit.

Now I could outline a lot of things the police do that really works against their goals, as impossible as they may seem. The same could be said for teachers (as a group, remember, when we personalize these things, make them about that officer I know, that teacher who lives under the same roof, the whole conversation gets pulled out of context). It doesn't take a genius to see that things can and should be done differently. That's what people criticize. We've got neighborhoods out there where kids are more likely to end up in prison than college - that shouldn't necessarily demean that police and teachers who work hard to change the situation, but it's also a pretty strong condemnation of both systems in which they work.

I guess my point is that it's the same story. One gets used as a liberal crusade and the other to bolster conservative ranks. There are lots of kids convinced the cops are out to get them; a lot feel the same way about teachers. On the whole, that notion is silly and paranoid, but not all of those kids are wrong. There's the rub.

When things are broken, it's easier to blame someone else than roll up one's own sleeves. We can conveniently point to the people specifically charged with handling that "problem," and replace them if they fail too badly. But the responsibility we put on people, like police or teachers, is not their responsibility, it's our collective responsibility. There's a lot of good, sincere people attempting to do both of these jobs - just because some of them could be better, the drive and effort shouldn't be demeaned. The tight-knit unions that protect police and teachers don't do a lot to help society at large be sympathetic to the issues they face, but that shouldn't demean sincerity and commitment either.

The reality is that no hero's perfect, but also that no hero should ever be scared of admitting the truth of that statement. It's our responsibility to create the environment where that can happen. I suggest we do a better job of it before we go after "the other guy" or defend our own.

Labels:

complexity,

grace,

police,

politics,

responsibility,

society,

teachers,

unions

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)