There's been a lot of discussion about gun laws, self defense, and justice of late, mostly precipitated by the killing of Trayvon Martin, a 17 year old killed from Florida. Many people have shared opinions and argued back and forth. I have some thoughts about all of those issues - you're just not going to see them here. For the past several days, there's been one intriguing aspect of this story that's been on my mind.

When the President said, "If I had a son, he would look like Trayvon" what he said was correct, but the truth is, if any of us had a son, he would look like Trayvon. Ironically, crazy Newt Gingrich was the only person of note to bring this up. And while I disagree with his charges of race-baiting (and nearly every other things that comes out of his mouth), I do agree this statement highlights race and should be given additional notice.

I believe the quote, and others like it, is meant to draw attention to the very real possibility that being black in the United States (and nearly anywhere else), in and of itself, is more dangerous than being white. As obvious as this realization is to millions of black parents, it may have taken an event like this for it to really sink in for Barack Obama (and for many other parents).

I want to be careful here and not ignore the reality of racism and our collective denial of the real effects of slavery and segregation in this country. Even if race had nothing to do with the death of Trayvon Martin, it's certainly reminiscent of many other deaths in which race played a pivotal role.

In the President's statement, Trayvon was not just a child, but a black child - which, inadvertently, pushes those of us who will likely never have a black child into a second class of relatability. Of course, my righteous indignation does precisely the same thing - why does Trayvon's age make his death, under these circumstances, any more tragic?

As a Christian, I believe that life is precious, that the taking of life is always tragic - even if, on occasion, we find it regrettably necessary. I believe that when a human being takes life there is an incongruity with our own created nature - something damaged that requires divine intervention to be healed. I wonder if we assign these levels of tragedy to killings as an attempt to buffer ourselves from the very real effects of those others we deem justified?

I think we create these levels of tragedy specifically to correspond with ourselves. The more innocent, the more well-intentioned, the more responsible for others, the more physically similar to me, the more tragic the death. Is this ultimately a way of calling our own lives more worthy of continuing than others? This becomes vitally important if we're ever in a situation where our life is threatened. We have a built in excuse to "kill or be killed" - our death would be more tragic than their's.

It all leads me to ponder what sort of actions and thought patterns I should be practicing to enforce and instill the idea that my life is not more important than any other? If indeed there exists a situation in which "kill or be killed" are the only two options, the more tragic is to choose killing - after all, the victim doesn't have to live with the consequences.

Saturday, March 31, 2012

Friday, March 30, 2012

To Be or to Buy?

New feature on the blog, folks! We're taking questions! Well, sort of. A friend send me a message on Facebook asking me to comment on some thoughts he'd been having; I saw it as an opportunity to fill space here as I'm running short on ideas at the moment. Feel free to send questions my way and I'll try to find a way to answer them in a lengthy, yet thoughtful way.

And so...

I struggle with the liturgy/order of worship. I am talking about the commercialistic nature of it all and I'm sure you know what I mean... The whole mindset of, "let's have a 'good' service today" approach. I guess what messes with me is when you compare that to an Orthodox or RC mass, the mindset of most people is much different. It is purely to come to worship and receive Christ through the Eucharist. There is no evaluation of the band or if Father Joe 'connects with me or not.' At a gut level it just messes with me that the degree of people's worship has rests so heavily on a worship leader or a preacher. Again, it seems so Walmart-like... Who can present me with the best product?

My initial reaction is to say that high church traditions might be, to us low church evangelicals, a bit like the grass always being grenier on the other side of the fence. I've heard plenty of Catholics and Anglicans complain about the disconnect they have with the worship, that they don't, in fact, feel connected to anything beyond the level of familiarity.

In this, I think, we might find common ground in our complaints. It is our very familiarity with whatever liturgy our tradition embraces often leads to the desire to incorporate parts of other traditions (high church traditions can use some connection to the present and low church traditions can use some connection to the past). It is likely beneficial to broaden our horizons and include a wide variety of practices in worship drawn from beyond our own traditions. However, I'm not sure that really solves the problem expressed.

The deeper issue is likely engagement. Too often we feel as though worship is something we observe rather than something we embody. In a culture than functions to turn us from humans into consumers, it is our natural reaction to consume worship. We are defined by what we buy, eat, wear, use - and therefore our worship should be the most perfect and the coolest - so we can't do it ourselves; we're not good enough.

Despite a culture that forms us to consume, we do have an inherent, human need for connection - real connection, both with each other and with God. Corporate worship is the time we set aside to gather as God's people to be formed into the likeness of Christ. I take that purpose literally; the Church is the real body of Christ. It requires real participation - and, like our humanity, requires both physical and spiritual participation.

I think a lot of our issues in worship could be solved by honestly answering one question: what does our liturgy say about God? Not what we want it to say about God, but what our acts of worship really communicate. The answer is really into what we're being formed.

And so...

I struggle with the liturgy/order of worship. I am talking about the commercialistic nature of it all and I'm sure you know what I mean... The whole mindset of, "let's have a 'good' service today" approach. I guess what messes with me is when you compare that to an Orthodox or RC mass, the mindset of most people is much different. It is purely to come to worship and receive Christ through the Eucharist. There is no evaluation of the band or if Father Joe 'connects with me or not.' At a gut level it just messes with me that the degree of people's worship has rests so heavily on a worship leader or a preacher. Again, it seems so Walmart-like... Who can present me with the best product?

My initial reaction is to say that high church traditions might be, to us low church evangelicals, a bit like the grass always being grenier on the other side of the fence. I've heard plenty of Catholics and Anglicans complain about the disconnect they have with the worship, that they don't, in fact, feel connected to anything beyond the level of familiarity.

In this, I think, we might find common ground in our complaints. It is our very familiarity with whatever liturgy our tradition embraces often leads to the desire to incorporate parts of other traditions (high church traditions can use some connection to the present and low church traditions can use some connection to the past). It is likely beneficial to broaden our horizons and include a wide variety of practices in worship drawn from beyond our own traditions. However, I'm not sure that really solves the problem expressed.

The deeper issue is likely engagement. Too often we feel as though worship is something we observe rather than something we embody. In a culture than functions to turn us from humans into consumers, it is our natural reaction to consume worship. We are defined by what we buy, eat, wear, use - and therefore our worship should be the most perfect and the coolest - so we can't do it ourselves; we're not good enough.

Despite a culture that forms us to consume, we do have an inherent, human need for connection - real connection, both with each other and with God. Corporate worship is the time we set aside to gather as God's people to be formed into the likeness of Christ. I take that purpose literally; the Church is the real body of Christ. It requires real participation - and, like our humanity, requires both physical and spiritual participation.

I think a lot of our issues in worship could be solved by honestly answering one question: what does our liturgy say about God? Not what we want it to say about God, but what our acts of worship really communicate. The answer is really into what we're being formed.

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

An Unending Roller Coaster

Ethics is the philosophical study of principled action. A lot of definitions like to say it's got something to do with right and wrong, but really it's about what we think is right and wrong and why we think so.

Usually this question has to do with goals - what is the point of this action? What am I trying to accomplish? These goals are mostly all about the long term. Even when we're intensely focused on an immediate result, it's often a cog in a grander machine. I'm spending Saturday in the library to do well on this paper to get a good grade, to get into a good school, to secure a well-paying job, which will give me greater freedom to enjoy life.

Despite the focus on goals, ethics tells us that every goal comes from a presupposition, a principle we assume to be truth (whether we know it or not) and ultimately determines our actions. Tension in life, what moves us beyond instinct, is the struggle between competing goals. If your presupposition is that happiness comes through fulfilling desires, there might be an ethical struggle between eating that extra plate of nachos today and avoiding an extra half hour on the toilet tomorrow.

It becomes a discussion of ends and means; what means will I use to achieve the ends my principles demand? This becomes more difficult when the decision moves beyond timing to morality itself. Is killing one person right, when it potentially saves the lives of ten or a hundred others? In this case, the goal is saving lives; the means might be to violate this truth for a more complete fulfillment in the long run. This is where we get, "the ends justify the means."

Over the last year, I've come to one interesting realization. As a follower of Christ, this idea of ends and means don't really apply. It's more than simply disagreeing that the ends justify the means, but a disavowal of the whole ends/means system.

If our grounding principle is that Jesus Christ was raised from the dead as a precursor to universal resurrection and eternal life, then there is no "ends" in our equation. This is something that the idea of an afterlife confuses. Biblically, there is no afterlife, there is just life again - resurrection. You don't die in one world and wake up in another, you die in one world and then return to that world (albeit a redeemed version). There are no ends because there is no end.

That leaves followers of Christ with only means. We trust that whatever long term goals exist in life, they are the purview of God. Our task, as God's people is to focus on right action in each moment. We are a means people. Simply put, if we are to walk in the footsteps of Jesus, we are to love, to act selflessly, in each moment. The Christian presupposition is that the ends and means are one and the same.

This realization has an alarming effect. It's both imminently comfortable and deeply challenging. We're trained to be ends and means people; it's ironically instinctual how this internal analysis is so ingrained. Most ethics is simply recognizing these inherent and unconscious principles and prioritizing our goals. With Christ, ethics involves learning an entirely different system; it requires a change in our very nature.

Usually this question has to do with goals - what is the point of this action? What am I trying to accomplish? These goals are mostly all about the long term. Even when we're intensely focused on an immediate result, it's often a cog in a grander machine. I'm spending Saturday in the library to do well on this paper to get a good grade, to get into a good school, to secure a well-paying job, which will give me greater freedom to enjoy life.

Despite the focus on goals, ethics tells us that every goal comes from a presupposition, a principle we assume to be truth (whether we know it or not) and ultimately determines our actions. Tension in life, what moves us beyond instinct, is the struggle between competing goals. If your presupposition is that happiness comes through fulfilling desires, there might be an ethical struggle between eating that extra plate of nachos today and avoiding an extra half hour on the toilet tomorrow.

It becomes a discussion of ends and means; what means will I use to achieve the ends my principles demand? This becomes more difficult when the decision moves beyond timing to morality itself. Is killing one person right, when it potentially saves the lives of ten or a hundred others? In this case, the goal is saving lives; the means might be to violate this truth for a more complete fulfillment in the long run. This is where we get, "the ends justify the means."

Over the last year, I've come to one interesting realization. As a follower of Christ, this idea of ends and means don't really apply. It's more than simply disagreeing that the ends justify the means, but a disavowal of the whole ends/means system.

If our grounding principle is that Jesus Christ was raised from the dead as a precursor to universal resurrection and eternal life, then there is no "ends" in our equation. This is something that the idea of an afterlife confuses. Biblically, there is no afterlife, there is just life again - resurrection. You don't die in one world and wake up in another, you die in one world and then return to that world (albeit a redeemed version). There are no ends because there is no end.

That leaves followers of Christ with only means. We trust that whatever long term goals exist in life, they are the purview of God. Our task, as God's people is to focus on right action in each moment. We are a means people. Simply put, if we are to walk in the footsteps of Jesus, we are to love, to act selflessly, in each moment. The Christian presupposition is that the ends and means are one and the same.

This realization has an alarming effect. It's both imminently comfortable and deeply challenging. We're trained to be ends and means people; it's ironically instinctual how this internal analysis is so ingrained. Most ethics is simply recognizing these inherent and unconscious principles and prioritizing our goals. With Christ, ethics involves learning an entirely different system; it requires a change in our very nature.

Monday, March 26, 2012

Back in the Saddle Again

So, Tiger Woods won his first PGA tour event in almost 1,000 days this weekend. It's been since his now famous Thanksgiving auto-accident, which may or may not have included a really high dose of sleeping pills and an enraged Swedish woman brandishing an incredibly expensive golf club. What is definitely included was Tiger's wife confronting him about a series of terribly traitorous affairs.

That personal tragedy, combined with some serious knee problems made for three down years for the world's greatest golfer. A likable, nice guy - destined for stardom from the age of two. He married a gorgeous model, had two beautiful kids and more money than God.

I'm not going to dwell on the speculation. Is Tiger a sex addict? Maybe. The tales of his escapades certainly don't fit entirely the model for a cheating rich guy. Did the absence of his father lead him astray? Certainly the role models he chose upon his father's death are better examples of selfish, entitled athletes (it's not like Michael Jordan or Charles Barkley have had a lot of marriage success).

Tiger's tragedy is not an uncommon one. We'll probably never know whether he was truly sorry or simply sorry he got caught. I'm pretty confident he loves his kids and probably still loves his now ex-wife. I'm not sure he does, or ever did, love them more than himself.

I appreciate some of the changes he's made - dropping friends who enabled him and embracing a few who seem to genuinely care (Roger Federer knows how to be the best in the world and is also, by all accounts, a committed family man). He got rough treatment for the way he fired caddie and former best friend, Steve Williams. Obviously it could have gone better, but the people who don't have our best interests in mind don't usually change their tune when the relationship comes to an end.

So many people are unhappy with Tiger. There's a lot of people rooting for him to lose. Tiger's screwed up royally and quite honestly he doesn't deserve anyone's sympathy or forgiveness; I'm not sure he's ever asked or cared. I do think measuring worth has no place in forgiveness anyway.

There's a lot to respect in Tiger's focus and discipline on the course, but he's still just a human being. He stopped being a person society could respect; will society learn the lesson when he returns to respectability?

Tiger Woods shouldn't have been a role model, even when he was a well-behaved clean-cut golfer. Perhaps that's the problem: we live in a society that doesn't quite know how to define success and therefore doesn't know what to look for in an example. We're a dichotomous society - we want heroes who give us permission to be self-indulgent, but we also want them to be happy, well-balanced individuals.

The trouble is simply that those two things don't go together. The only way to satisfy that burning desire inside us to be fulfilled is, paradoxically, to forget ourselves and think of others, serve others, love others.

Tiger Woods certainly learned one way it doesn't work; he's also got plenty of opportunity to serve others. The choice is whether he's going to allow his life to be centered around him once again or if he'll really be different. That's almost as exciting to watch as his assault on the record books.

That personal tragedy, combined with some serious knee problems made for three down years for the world's greatest golfer. A likable, nice guy - destined for stardom from the age of two. He married a gorgeous model, had two beautiful kids and more money than God.

I'm not going to dwell on the speculation. Is Tiger a sex addict? Maybe. The tales of his escapades certainly don't fit entirely the model for a cheating rich guy. Did the absence of his father lead him astray? Certainly the role models he chose upon his father's death are better examples of selfish, entitled athletes (it's not like Michael Jordan or Charles Barkley have had a lot of marriage success).

Tiger's tragedy is not an uncommon one. We'll probably never know whether he was truly sorry or simply sorry he got caught. I'm pretty confident he loves his kids and probably still loves his now ex-wife. I'm not sure he does, or ever did, love them more than himself.

I appreciate some of the changes he's made - dropping friends who enabled him and embracing a few who seem to genuinely care (Roger Federer knows how to be the best in the world and is also, by all accounts, a committed family man). He got rough treatment for the way he fired caddie and former best friend, Steve Williams. Obviously it could have gone better, but the people who don't have our best interests in mind don't usually change their tune when the relationship comes to an end.

So many people are unhappy with Tiger. There's a lot of people rooting for him to lose. Tiger's screwed up royally and quite honestly he doesn't deserve anyone's sympathy or forgiveness; I'm not sure he's ever asked or cared. I do think measuring worth has no place in forgiveness anyway.

There's a lot to respect in Tiger's focus and discipline on the course, but he's still just a human being. He stopped being a person society could respect; will society learn the lesson when he returns to respectability?

Tiger Woods shouldn't have been a role model, even when he was a well-behaved clean-cut golfer. Perhaps that's the problem: we live in a society that doesn't quite know how to define success and therefore doesn't know what to look for in an example. We're a dichotomous society - we want heroes who give us permission to be self-indulgent, but we also want them to be happy, well-balanced individuals.

The trouble is simply that those two things don't go together. The only way to satisfy that burning desire inside us to be fulfilled is, paradoxically, to forget ourselves and think of others, serve others, love others.

Tiger Woods certainly learned one way it doesn't work; he's also got plenty of opportunity to serve others. The choice is whether he's going to allow his life to be centered around him once again or if he'll really be different. That's almost as exciting to watch as his assault on the record books.

Labels:

forgiveness,

Love,

selfishness,

selflessness,

sports,

success,

Tiger Woods

Saturday, March 24, 2012

The Making of a Nerdling

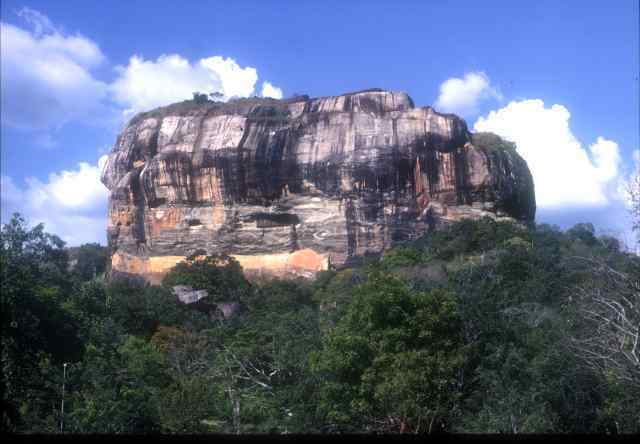

This is Sigiriya, a large rock on an island nation that was once home to a local monarch who used slave labor to haul water to the top. That was all the information I had (along with a picture very similar this one) in the final round of the Vermont State Geography Bee in 1993. In fact I don't recall them even giving me the name of the rock; I just had to name the island nation.

The answer is Sri Lanka. I got it wrong. I can't remember what I actually said, although Indonesia seems most likely. I knew the rest of the questions asked in the competition, and the guy who won ended up on TV, in the top ten at the National Bee. On occasion, that crazy mountain still haunts me.

I've been reminiscing about my Geography Bee years since reading a chapter on it this morning from Ken Jennings' Maphead. The National Geography Bee was founded in 1988 by National Geographic Magazine as a response too poor geography knowledge among the nation's school children. Kids in 4th through 8th grade compete at the school level and the local winner takes a written test. The top 100 scores move on to the State Bee, which in turn sends its champion to Washington, DC, where the top ten competitors gets to play for a $25,000 scholarship on PBS in an event hosted by Alex Trebek.

The Gifted/Talented teacher at my elementary school let me participate in the school bee in 1990, as a third grader. The school was small, the bee was young; she probably wanted to make it seem more popular. I won. I remember the last question was "What is the only country in the world through which passes both the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn. The other girl said Zaire, I picked Brazil. She still got to take the written test, as I was too young. I did manage to compete in the State Bee all five of me eligible years, but it was 6th grade that proved to be my best shot.

Jennings brings out what is the most surprising and important element of the Bee. It's not about memorizing capitals and rivers; the Bee does a fantastic job about testing a deeper, more thorough knowledge of geography. As evidenced by the Sri Lankan mountain above, most questions required an educated guess rather than a memorized fact. My knowledge of geography certainly isn't as sharp as it once was, even so, the 2009 Bee (that Jennings profiles) shows just how far the whole experience has come. The depth of knowledge required is insane. Every kid in DC would not only know what country that rock is in, but how tall it is, how many people visit it each year, and the middle name of the first white guy to see it.

One of my major flaws is that I tend to think I'm better at things than I really am. I'm good at trivial pursuit, but if I actually got on Jeopardy would I be able to blow everyone away? Probably not. I still believe I had a chance to win that Geography Bee had I just managed to come up with Sri Lanka, but I can in no way claim to have been as smart as the kids who win it these days.

I've often wondered if that outrageous sense of self-importance, one that tends to lack ego as much as it includes a basic ignorance of the world, is what breeds a nerd, dork, dweeb, geek or whatever you want to call us socially awkward intellectual types. Whether it's a type or just an subconscious attempt on my part to justify some seriously self-centered behavior, I've come to realize that this nerd quality, something I've used to positive define myself my entire life, might just be less important than actually helping and being present to other people.

Nothing ground breaking there. Lots of people realize as they mature that giving up selfish pursuits for the sake of meaningful relationships is a prerequisite for living in the world. Ir just feels good, now and then, to relive a little of that faded glory.

The answer is Sri Lanka. I got it wrong. I can't remember what I actually said, although Indonesia seems most likely. I knew the rest of the questions asked in the competition, and the guy who won ended up on TV, in the top ten at the National Bee. On occasion, that crazy mountain still haunts me.

I've been reminiscing about my Geography Bee years since reading a chapter on it this morning from Ken Jennings' Maphead. The National Geography Bee was founded in 1988 by National Geographic Magazine as a response too poor geography knowledge among the nation's school children. Kids in 4th through 8th grade compete at the school level and the local winner takes a written test. The top 100 scores move on to the State Bee, which in turn sends its champion to Washington, DC, where the top ten competitors gets to play for a $25,000 scholarship on PBS in an event hosted by Alex Trebek.

The Gifted/Talented teacher at my elementary school let me participate in the school bee in 1990, as a third grader. The school was small, the bee was young; she probably wanted to make it seem more popular. I won. I remember the last question was "What is the only country in the world through which passes both the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn. The other girl said Zaire, I picked Brazil. She still got to take the written test, as I was too young. I did manage to compete in the State Bee all five of me eligible years, but it was 6th grade that proved to be my best shot.

Jennings brings out what is the most surprising and important element of the Bee. It's not about memorizing capitals and rivers; the Bee does a fantastic job about testing a deeper, more thorough knowledge of geography. As evidenced by the Sri Lankan mountain above, most questions required an educated guess rather than a memorized fact. My knowledge of geography certainly isn't as sharp as it once was, even so, the 2009 Bee (that Jennings profiles) shows just how far the whole experience has come. The depth of knowledge required is insane. Every kid in DC would not only know what country that rock is in, but how tall it is, how many people visit it each year, and the middle name of the first white guy to see it.

One of my major flaws is that I tend to think I'm better at things than I really am. I'm good at trivial pursuit, but if I actually got on Jeopardy would I be able to blow everyone away? Probably not. I still believe I had a chance to win that Geography Bee had I just managed to come up with Sri Lanka, but I can in no way claim to have been as smart as the kids who win it these days.

I've often wondered if that outrageous sense of self-importance, one that tends to lack ego as much as it includes a basic ignorance of the world, is what breeds a nerd, dork, dweeb, geek or whatever you want to call us socially awkward intellectual types. Whether it's a type or just an subconscious attempt on my part to justify some seriously self-centered behavior, I've come to realize that this nerd quality, something I've used to positive define myself my entire life, might just be less important than actually helping and being present to other people.

Nothing ground breaking there. Lots of people realize as they mature that giving up selfish pursuits for the sake of meaningful relationships is a prerequisite for living in the world. Ir just feels good, now and then, to relive a little of that faded glory.

Thursday, March 22, 2012

Left Behind?

I wrote a little about this in a previous post, but the topic has come up again. Rachel Held Evans, who has figured out a way to make just about anything she writes go viral, wrote two pieces this week about why she left church and why she's returned to the Church, even if in non-traditional form. It's spurred furious conversation across the social media stream - and it's something near to my heart.

A lot of these issues and questions are those with which I've struggled and wrestled over the past decade or so. I, unlike many, was fortunate to have found a supportive and encouraging community at Nazarene Theological Seminary. It was a safe place to think and explore, peopled with experienced mentors who foster a safe place to work out your faith with fear and trembling. Actually, there was not much fear or trembling - usually just encouragement that others have made a similar journey and come out healthy on the other side.

It breaks my heart that others have not had similar support in their struggles and have made the sad decision to disengage from a faith community. There is a growing divide. When I talk to my peers and those younger (a group which is growing disturbingly large with each passing day) these concerns are almost unquestioningly understood, even if they're not shared. There is a sense of space and freedom present that just doesn't seem to jibe with the attitude of previous generations.

I think there is something to the sociological proposition that these postmodern generations have a lack of faith in, or reliance upon, institutions. We're just more comfortable with ambiguity. I have seen, in my own denomination, how unprepared the system is for the force of change already deeply embedded in the next generation of leadership. Things are going to look very different.

As we prepare to embark on an unknown journey, it's a bit daunting to do so without specifics. I've got a real burden to provide a safe place for people, like Rachel and so many of my friends, to explore and seek and doubt without having to give up a community of faith - even to provide a community of faith that isn't defined entirely by what we believe so much as what we're after (and I do wholeheartedly believe we're all after God).

It's easy to doubt we'll see any success. After all how many people out there are really interested in thinking deeply about anything in this superficial day and age? There are these cries of solidarity that help to reinforce this belief with reality. Even as those kindred spirits seem so few and far between, I have to trust that God will draw us together and others from the woodwork as we take the risk to be open and honest.

I don't believe God is intimidated by our internal complexities; I sort of believe they are intentional.

A lot of these issues and questions are those with which I've struggled and wrestled over the past decade or so. I, unlike many, was fortunate to have found a supportive and encouraging community at Nazarene Theological Seminary. It was a safe place to think and explore, peopled with experienced mentors who foster a safe place to work out your faith with fear and trembling. Actually, there was not much fear or trembling - usually just encouragement that others have made a similar journey and come out healthy on the other side.

It breaks my heart that others have not had similar support in their struggles and have made the sad decision to disengage from a faith community. There is a growing divide. When I talk to my peers and those younger (a group which is growing disturbingly large with each passing day) these concerns are almost unquestioningly understood, even if they're not shared. There is a sense of space and freedom present that just doesn't seem to jibe with the attitude of previous generations.

I think there is something to the sociological proposition that these postmodern generations have a lack of faith in, or reliance upon, institutions. We're just more comfortable with ambiguity. I have seen, in my own denomination, how unprepared the system is for the force of change already deeply embedded in the next generation of leadership. Things are going to look very different.

As we prepare to embark on an unknown journey, it's a bit daunting to do so without specifics. I've got a real burden to provide a safe place for people, like Rachel and so many of my friends, to explore and seek and doubt without having to give up a community of faith - even to provide a community of faith that isn't defined entirely by what we believe so much as what we're after (and I do wholeheartedly believe we're all after God).

It's easy to doubt we'll see any success. After all how many people out there are really interested in thinking deeply about anything in this superficial day and age? There are these cries of solidarity that help to reinforce this belief with reality. Even as those kindred spirits seem so few and far between, I have to trust that God will draw us together and others from the woodwork as we take the risk to be open and honest.

I don't believe God is intimidated by our internal complexities; I sort of believe they are intentional.

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Don't Hate the Player

Worship gets a bad wrap... or maybe an insufficient one? For those who have grown up in church, worship is usually an hour on Sunday morning. More recently, it's come to be just the songs you sing during that hour. I can't speak for the meaning of worship to those who haven't grown up in church, I've been attending worship services all my life.

Is it peculiar we call them worship services? Doesn't service imply an action? Most Christian worship services I've attended are basically passive. We might be invited to stand or bow our heads or sing along, but they're awfully static.

What is worship supposed to be? The idea of service indicates something we do. My understanding of theology indicates it's something we do in response to something God does and with the expectation that God will do something else.

We gather because God has created us and the world around us and has embodied love for us. My tradition believe that in all times and all places the Spirit of God is calling out to all people. Our acts (service) of worship are a response to that calling. Likewise, we act in specific ways (although our ways might could use with some greater creativity). We do so with expectation that in these acts God will shape us and form us into the likeness of Jesus Christ, who is and embodies all we were created to be.

That, conveniently, brings me to the not so subtle, nor unintentional question that springs from such a lengthy introduction: why is our service of worship an hour on Sunday mornings (or in the case of hipsters and non-English services, Sunday afternoon, evening or Saturday night)? And if our acts of worship allow God to shape and form us into Christ, what do the other acts we do the other 167 hours do for us (or to us)?

I'd like to get away from acts of worship overtly connected to a structure - not that structure is bad, it's completely necessary - but an institutionalized structure tends to have us looking over our shoulder for permission to do something different. Is there a way to engage in a life of worship as the overarching organizational element and subsume structure as merely an element?

I don't want to downplay the importance of corporate worship. I believe wholeheartedly that we cannot exist purely as individuals, nor were we ever meant to do so. We need connection and community; we need corporate worship. We even need to sing together, pray together, confess together, read scripture together, and receive a sermon together. It's just that we also need to live together, eat together, serve together, mourn together, argue together, doubt together, and just sit together.

What if worship was more than something we do?

Is it peculiar we call them worship services? Doesn't service imply an action? Most Christian worship services I've attended are basically passive. We might be invited to stand or bow our heads or sing along, but they're awfully static.

What is worship supposed to be? The idea of service indicates something we do. My understanding of theology indicates it's something we do in response to something God does and with the expectation that God will do something else.

We gather because God has created us and the world around us and has embodied love for us. My tradition believe that in all times and all places the Spirit of God is calling out to all people. Our acts (service) of worship are a response to that calling. Likewise, we act in specific ways (although our ways might could use with some greater creativity). We do so with expectation that in these acts God will shape us and form us into the likeness of Jesus Christ, who is and embodies all we were created to be.

That, conveniently, brings me to the not so subtle, nor unintentional question that springs from such a lengthy introduction: why is our service of worship an hour on Sunday mornings (or in the case of hipsters and non-English services, Sunday afternoon, evening or Saturday night)? And if our acts of worship allow God to shape and form us into Christ, what do the other acts we do the other 167 hours do for us (or to us)?

I'd like to get away from acts of worship overtly connected to a structure - not that structure is bad, it's completely necessary - but an institutionalized structure tends to have us looking over our shoulder for permission to do something different. Is there a way to engage in a life of worship as the overarching organizational element and subsume structure as merely an element?

I don't want to downplay the importance of corporate worship. I believe wholeheartedly that we cannot exist purely as individuals, nor were we ever meant to do so. We need connection and community; we need corporate worship. We even need to sing together, pray together, confess together, read scripture together, and receive a sermon together. It's just that we also need to live together, eat together, serve together, mourn together, argue together, doubt together, and just sit together.

What if worship was more than something we do?

Thursday, March 15, 2012

Theological Mumbo Jumbo

I've always been fascinated by the concept of religionless Christianity as proposed by Dietrich Bonhoeffer. He was a German pastor and professor, who led the "confessing church" as a protest to the mainstream church that sold out to Hitler during his rise. He continues to be one of the foremost thinkers to influence my own understanding of Christian life.

Unfortunately, Bonhoeffer was executed by the Nazis before he really had a chance to flesh out these ideas in practice. Lately, a host of young Christians are beginning to explore what it means to be faithful to a lived out gospel in our present cultural context.

Peter Rollins is an Irish philosopher and author who is exploring, in thought and practice, exactly what it looks like to participate in religionless Christianity. I've found a lot in his writing and speaking, that has caused me to think about what it means to believe and what it means to be a Christian.

His basic premise is that belief comes not from what we say we believe, but from how we act. The fault of religion, at least in this context, is that it spends too much time and energy on what to believe and not nearly enough on actually believing/living it. We should be constantly challenged by God, through scripture - the story of God, but this should be means to an end and not an end in itself.

The idea of Christianity is to be formed in the image of Christ. Our participation in Christianity should be engagement in practices that allow God to shape us into the people we're created to be. In the scope of modern, intellectual understanding these became condensed into listening and reading - hearing sermons and studying books about belief. Don't get me wrong, I'm an intellectual whether I like it or not, these practices are important; they're just insufficient.

They help us understand and recognize the beliefs we should hold - they're wonderful at developing intellectual assent, a powerful element of self-realization. What they lack, is the physical, formational ability required for true belief. There are some of us, motivated by intellectual assent, who will change our habits and thus exercise belief. Speaking strictly for myself, I just don't have the discipline to do so.

As we embark on this Grand Experiment, we'll be seeking to fully discern and implement these practices in ways that shape and form us into the kind of community we seek. Some of these make sense when it's just the three of us (along with the wife and baby): like serving in local community organizations, sharing a meal with friends, enjoying creation, helping those in need, etc. Other practices are more difficult - corporate worship for example.

The biggest question I have, one we'll have to wrestle with as we go, is how to maintain Christ as the center point around which these practice revolve. Obviously, Christ is central for us, but as we engage people in practices not traditionally or exclusively associated with Christian practice (service, creation care, etc), will we be able to effectively communicate our motivation and framework?

We shall see.

Unfortunately, Bonhoeffer was executed by the Nazis before he really had a chance to flesh out these ideas in practice. Lately, a host of young Christians are beginning to explore what it means to be faithful to a lived out gospel in our present cultural context.

Peter Rollins is an Irish philosopher and author who is exploring, in thought and practice, exactly what it looks like to participate in religionless Christianity. I've found a lot in his writing and speaking, that has caused me to think about what it means to believe and what it means to be a Christian.

His basic premise is that belief comes not from what we say we believe, but from how we act. The fault of religion, at least in this context, is that it spends too much time and energy on what to believe and not nearly enough on actually believing/living it. We should be constantly challenged by God, through scripture - the story of God, but this should be means to an end and not an end in itself.

The idea of Christianity is to be formed in the image of Christ. Our participation in Christianity should be engagement in practices that allow God to shape us into the people we're created to be. In the scope of modern, intellectual understanding these became condensed into listening and reading - hearing sermons and studying books about belief. Don't get me wrong, I'm an intellectual whether I like it or not, these practices are important; they're just insufficient.

They help us understand and recognize the beliefs we should hold - they're wonderful at developing intellectual assent, a powerful element of self-realization. What they lack, is the physical, formational ability required for true belief. There are some of us, motivated by intellectual assent, who will change our habits and thus exercise belief. Speaking strictly for myself, I just don't have the discipline to do so.

As we embark on this Grand Experiment, we'll be seeking to fully discern and implement these practices in ways that shape and form us into the kind of community we seek. Some of these make sense when it's just the three of us (along with the wife and baby): like serving in local community organizations, sharing a meal with friends, enjoying creation, helping those in need, etc. Other practices are more difficult - corporate worship for example.

The biggest question I have, one we'll have to wrestle with as we go, is how to maintain Christ as the center point around which these practice revolve. Obviously, Christ is central for us, but as we engage people in practices not traditionally or exclusively associated with Christian practice (service, creation care, etc), will we be able to effectively communicate our motivation and framework?

We shall see.

Friday, March 09, 2012

Wave of the Future

After we announced to our congregation last Sunday that we were leaving this summer to embark on our Grand Experiment, I returned home to find the new TIME Magazine waiting for me. The cover story was really ten small articles about the ways the world has changed around us, often without us even noticing.

On page 68, #4 in the list of ten was entitled, "The Rise of the Nones." It focused mostly on surprising poll numbers in the US that show a drastic increase in the number of people who claim no religious affiliation and at the same time only 4% of people claim to be atheist or agnostic. What this means is that people are being turned off by organized religion, but not so much with the idea of God. In fact, the article cites that "40% of unaffiliated people are fairly religious" in belief and practice.

There was a focus on one small community of US ex-pats in Mexico, led by an ordained Presbyterian minister, who have formed "Not Church." Not Church is a community of people who share life together under the umbrella of Christian faith, but without the trappings of ecclesiastical hierarchy and theological disputes.

I immediately thought of the "belong, believe, behave" debates that have happened in recent years. The old model was convincing people to behave a certain way (stop drinking, smoking, sleeping around, etc), which would open them up to belief in God, which in turn would allow them to belong to the congregation. Recently things have been switched up. People are desperately seeking ways to connect to other people. Congregations like "Not Church" provide a place for people to belong, exploring the ideas presented and developing belief, wherein they use this belief to make decisions about behavior.

People need relationship, trust, before they're willing to evaluate beliefs and behaviors. Quite honestly, people need relationship and community to wrestle with the "big questions" in life. It's not something we're meant to do alone. This provision of a community should also not be conceived as a means to evangelism, but as an end in itself. Providing such a community gives people space to explore their own lives; it's not a tool for building attendance or religious structures (at least it shouldn't be, although I suspect it's already being commodified for use toward those purposes anyway).

As we've been discussing our new adventure, people have had some difficulty understanding what exactly we're intending to do. I'm not sure we know exactly, but these issues are some we feel called to engage. We hope to find and provide a safe, loving community that can live life together as we explore God's creative purpose for our lives.

On page 68, #4 in the list of ten was entitled, "The Rise of the Nones." It focused mostly on surprising poll numbers in the US that show a drastic increase in the number of people who claim no religious affiliation and at the same time only 4% of people claim to be atheist or agnostic. What this means is that people are being turned off by organized religion, but not so much with the idea of God. In fact, the article cites that "40% of unaffiliated people are fairly religious" in belief and practice.

There was a focus on one small community of US ex-pats in Mexico, led by an ordained Presbyterian minister, who have formed "Not Church." Not Church is a community of people who share life together under the umbrella of Christian faith, but without the trappings of ecclesiastical hierarchy and theological disputes.

I immediately thought of the "belong, believe, behave" debates that have happened in recent years. The old model was convincing people to behave a certain way (stop drinking, smoking, sleeping around, etc), which would open them up to belief in God, which in turn would allow them to belong to the congregation. Recently things have been switched up. People are desperately seeking ways to connect to other people. Congregations like "Not Church" provide a place for people to belong, exploring the ideas presented and developing belief, wherein they use this belief to make decisions about behavior.

People need relationship, trust, before they're willing to evaluate beliefs and behaviors. Quite honestly, people need relationship and community to wrestle with the "big questions" in life. It's not something we're meant to do alone. This provision of a community should also not be conceived as a means to evangelism, but as an end in itself. Providing such a community gives people space to explore their own lives; it's not a tool for building attendance or religious structures (at least it shouldn't be, although I suspect it's already being commodified for use toward those purposes anyway).

As we've been discussing our new adventure, people have had some difficulty understanding what exactly we're intending to do. I'm not sure we know exactly, but these issues are some we feel called to engage. We hope to find and provide a safe, loving community that can live life together as we explore God's creative purpose for our lives.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)