I'll be honest, when I got more than halfway through this book and we were still doing, essentially, preliminary work - setting the stage for a discussion of atonement and salvation - I was a little worried. Yes, because Eric and I had similar theological training (we were even in a class or two together in seminary), much of the important groundwork for his presentation is are things I take for granted. It's not that any of it was unnecessary, in fact I think it makes this book incredibly accessible, it's just that I like to read books for new information, and I was in near total agreement for the first 80 pages. Well, I'm in near-total agreement for the entire book, but you get the idea.

What I needed to do was get out of my own head and read Atonement and Salvation with a little more distance. In truth, it is one the most clear and concise treatments of, really, the whole of Christian theology, I have ever read. While the prose may not be the most elegant you've ever seen, it's clear and insightful - you can tell Vail took great, great care in crafting this book.

What shocked me out of my self-oriented perspective was Chapter 8, where he gets to the real meat of the Atonement and Salvation discussion. Chapter 8 is perhaps the most powerful, important, and accessible chapter of theology I have ever read in any book. It's simply tremendous, maybe not for my personal growth, but as a resource for introducing the average Christian to what has always been a difficult and confusing topic. He builds on all that important preliminary material and crafts a picture of atonement that rings true to experience and reflects the massive, unfathomable love of God, while also taking seriously the whole witness of scripture in really responsible ways.

The final two chapters deal with smaller associated topics, including Christ as peacemaker and a critique of penal substitution theory that both pulls no punches, but also exhibits incredible grace. I began the book wondering who it could possibly be for - it doesn't largely break new ground academically and I couldn't imagine any lay person would want to or be able to work through 141 pages on atonement, but Eric Vail has done it. He presents the theology in an academic and compelling way, but with the deft and simplicity that would allow intent readers of any theological depth to follow the narrative and understand his presentation.

Atonement and Salvation is a real gift to the Church and I'm glad the Nazarene Publishing House continues to cultivate and publish such important material.

Thursday, December 22, 2016

Thursday, December 08, 2016

Build Your Hopes on Things Eternal

I spent some time this morning trying to see if I could adapt Hauerwas and Willimon's Resident Aliens for an adult Sunday School class. Scott Daniels is a man of great wisdom who told me he'd tried in once and the book was just too dense for such a setting. I tried to do it anyway, but his advice allowed me to give up the ghost one chapter in. It's a great chapter, though, and I don't want to waste the effort.

The idea of Resident Aliens is primarily that the Church is a "colony of heaven," in the way that conquerors (they might call themselves explorers or liberators) develop colonies in new lands, which are reflective of the home culture, so the Church is called to be a colony of a different world in the midst of this world. A Greek colony in Egypt would've maintained the Greek attitudes towards education, commerce, and social relations, despite those things being at odds with the larger world they find themselves living in.

Christians are called to live differently - not to make the world in which they live more Christian, but to present an alternative means of living - one reflective of God's intentions for the world as revealed in Christ. Christ then becomes the key to all this. The book says that when Christians look a the world, we see something that cannot be seen without Christ - the story of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection provides a lens by which we see the whole concept of life differently.

I was reminded of a song we sung in worship a few weeks back. It's entitled "Hold to God's Unchanging Hand," and contains a line that really caught my attention: "Build your hopes on things eternal," which I imagine has traditionally been looked upon as escapist. There's a long modern Christian tradition of viewing the world as imperfect and temporary, thus the common advice when things go poorly is "don't worry, there's another world out there somewhere; think about eternity."

I see this line more in terms of what Hauerwas and Willimon are trying to say: that there is an entirely different way of looking at this world, an eternal view, a "heavenly" view, something more reflective of what God has in mind, as revealed in Christ.

This difference shows up in the second challenge of Resident Aliens' first chapter: to ask the right theological questions. The authors argue that we typically engage the politics of the world on their own terms - this stretches all the way back to Constantine, the Roman Emperor who first embraced Christianity as a unifying force. Since then we've largely asked "how can we run this world in Christian ways?" It's become a political preoccupation that's gotten us nothing but trouble. Instead, what Willimon and Hauerwas propose is that we ask "What would the world look like if it reflected the gospel?"

This is what I think of when I hear, "Build your hopes on things eternal." We don't have to take the systems and structures we have as inevitable. God calls us to build our lives on a different set of principles and realities, to be a true alternative to the way things seem to work in the world around us. This is the colony concept; the Church's purpose is to be something different, not take the world around us and make it different.

I know the immediate "but" in this is "but if you succeed in building an alternative, won't that just attract 'the world' to join, thereby changing the world into something Christian?" In a sense, yes, of course that leads into conversations about HOW precisely that is done - through an actual attempt to change or through a faithful representation of an alternative - but even that is getting ahead of ourselves, right? We're assuming that living faithfully into an alternative is easy - that establishing and maintain this colony of heaven is a given. It's hard work.

The book goes on to talk specifically about how our politics (in whatever way we've worked them out) have failed us and challenging the Church to a new kind of politics, one that operate on its own system, rather than trying to co-opt the systems around us. There's plenty to delve into there, and I'd love to have those conversations if you want to dialogue about them, but I think this first notion is a really important start.

Build your life on things eternal is not about spiritualizing everything, but it's also not about digging in to physical-ize everything either. We've had quite enough of activist Christianity already. I think rather the call is to have our foundational understandings shaped and formed by the gospel rather than by the world in which we live. We have to stop taking for granted the "realities" we're presented with and imagine our realities in light of God's revelation in Christ.

Well, just some random thoughts on a Thursday. Cheerio.

The idea of Resident Aliens is primarily that the Church is a "colony of heaven," in the way that conquerors (they might call themselves explorers or liberators) develop colonies in new lands, which are reflective of the home culture, so the Church is called to be a colony of a different world in the midst of this world. A Greek colony in Egypt would've maintained the Greek attitudes towards education, commerce, and social relations, despite those things being at odds with the larger world they find themselves living in.

Christians are called to live differently - not to make the world in which they live more Christian, but to present an alternative means of living - one reflective of God's intentions for the world as revealed in Christ. Christ then becomes the key to all this. The book says that when Christians look a the world, we see something that cannot be seen without Christ - the story of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection provides a lens by which we see the whole concept of life differently.

I was reminded of a song we sung in worship a few weeks back. It's entitled "Hold to God's Unchanging Hand," and contains a line that really caught my attention: "Build your hopes on things eternal," which I imagine has traditionally been looked upon as escapist. There's a long modern Christian tradition of viewing the world as imperfect and temporary, thus the common advice when things go poorly is "don't worry, there's another world out there somewhere; think about eternity."

I see this line more in terms of what Hauerwas and Willimon are trying to say: that there is an entirely different way of looking at this world, an eternal view, a "heavenly" view, something more reflective of what God has in mind, as revealed in Christ.

This difference shows up in the second challenge of Resident Aliens' first chapter: to ask the right theological questions. The authors argue that we typically engage the politics of the world on their own terms - this stretches all the way back to Constantine, the Roman Emperor who first embraced Christianity as a unifying force. Since then we've largely asked "how can we run this world in Christian ways?" It's become a political preoccupation that's gotten us nothing but trouble. Instead, what Willimon and Hauerwas propose is that we ask "What would the world look like if it reflected the gospel?"

This is what I think of when I hear, "Build your hopes on things eternal." We don't have to take the systems and structures we have as inevitable. God calls us to build our lives on a different set of principles and realities, to be a true alternative to the way things seem to work in the world around us. This is the colony concept; the Church's purpose is to be something different, not take the world around us and make it different.

I know the immediate "but" in this is "but if you succeed in building an alternative, won't that just attract 'the world' to join, thereby changing the world into something Christian?" In a sense, yes, of course that leads into conversations about HOW precisely that is done - through an actual attempt to change or through a faithful representation of an alternative - but even that is getting ahead of ourselves, right? We're assuming that living faithfully into an alternative is easy - that establishing and maintain this colony of heaven is a given. It's hard work.

The book goes on to talk specifically about how our politics (in whatever way we've worked them out) have failed us and challenging the Church to a new kind of politics, one that operate on its own system, rather than trying to co-opt the systems around us. There's plenty to delve into there, and I'd love to have those conversations if you want to dialogue about them, but I think this first notion is a really important start.

Build your life on things eternal is not about spiritualizing everything, but it's also not about digging in to physical-ize everything either. We've had quite enough of activist Christianity already. I think rather the call is to have our foundational understandings shaped and formed by the gospel rather than by the world in which we live. We have to stop taking for granted the "realities" we're presented with and imagine our realities in light of God's revelation in Christ.

Well, just some random thoughts on a Thursday. Cheerio.

Labels:

church,

colony,

ecclesiology,

eternal,

hauerwas,

Heaven,

hymns,

life,

poliics,

purpose,

resident aliens,

scott daniels,

willimon

Tuesday, December 06, 2016

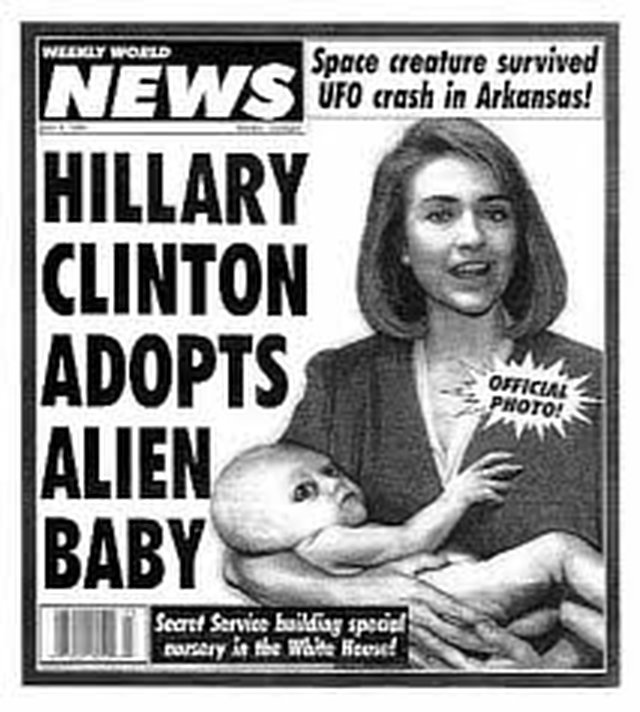

I Love Fake News

Maybe this has cycled out of the public consciousness in the weeks since the election, but I saw another story about it today, so why not wade in, right? I like fake news. I don't think it's a problem for anyone, except maybe actual journalists and their employers. The problem is us. People read "news" looking to have their own ideas reinforced and bolstered, seeking support for their "team" in this political game we call life. No one bother to double check a source or do their own research - we just decide if something makes sense and go with it.

If you really look at this "fake news" stuff, yeah there's some talk that it's being secretly funded by foreign governments to mess with US elections, but for the most part, it's a product of economic disparity in a globalized world. Most of this stuff comes from shops set up in rural Macedonia, where low-level gangsters pay school children to write (or even just copy and paste) stories about the US elections in their off hours. With the advent of online advertising, you don't need any actual substance, just a headline click-baity enough to draw interest. People get paid for the eyeballs on the ads - that's all that matters. Fake news is no different than kitten videos or clever memes - it's just content meant to make someone money.

It might be poor satire, but it's certainly inventive - well, some of it - the best fake news is genuinely creative and clever, people make up stories that other people want to read. We live in a world where almost everyone universally doubts the bias of the press, even historic, well-established journalistic brands - even if a fake news site bills itself as real news, people are conditioned not to trust media. Heck, even fake news sites like the Onion that are overtly up-front about the fakeness of their news still end up getting retweeted by actual elected officials.

The problem is not some masquerading pseudo-journalist who's really a fourth grader in Gostivar (look it up); the problem is us. The great Western Individualism that we've come to know and love (and claim is the reason much of those who hate us hate us) has led us to be self-absorbed egotists, assuming that our common sense is the closet approximation to truth. We're also lazy. It doesn't take much in this internet age to research a story and then utilize that profound common sense with, you know, a basic level of information. It's the same internet these fake news sites mine to figure out what stories we might click on and then provide them to us.

If you listen to any of the numerous reporting pieces on fake news, you can hear interviews with these kids and their bosses. They're not interested in shaping US policy (although they take pride in the fact that they are), they just want to make money. If people click on Trump stories, they'll write Trump stories. It's industrious and inventive and intelligent - all things you need to be to avoid falling for this kind of news.

I hear all this hand-wringing from people lamenting the place fake news held in the recent election and I've heard nothing about the responsibility of a society to educate its people and motivate them to perform basic functions. It's not like you have to drive down to some college library to look up economic charts from the past five years - you type a couple words into google and you click on a few "about us" tabs and then you click on google a few more times to verify the information you're finding.

Yeah, it's not perfect, but the more information one has the better capable we are of making real, informed choices. Not doing the work to be informed is our fault, not someone else's.

I love fake news. If I'd had time and a little more internet marketing savvy, it sounds like a fun way to make some money. I like writing. I'm pretty creative. I'm pretty knowledgeable about the political landscape. I bet I'd be really good at it. About ten years ago, when I had a break from grad school, I'd go onto Yahoo Answers and write long, details answers to questions that were entirely false. For example, one girl was trying to get help with her homework on Romeo and Juliet and I described in 1500 words, the plot of A Streetcar Named Desire (I just used the names Romeo and Juliet instead of Stanley and Stella).

There's really no excuse for believing something just because it sounds good. I imagine it has to do with our aversion to suffering - we only work as much as we have to work, and we try to avoid it as much as possible. Talk to a middle school teacher sometime - one of the most difficult things to teach is research - good research - it's too easy to get into a mindset of "it says this somewhere" and "their opinions is as valid as anyone else's." I don't disagree with the opinion part, but there's a certain level of knowledge that's assumed. Opinions are equally valid when they come from the same level of knowledge. My opinions on the origin of black holes is not nearly as valid as that of Neil DeGrasse Tyson. If I were ever going to disagree with him, I'd have to do a lot of actual work to gain the kind of knowledge I'd need to do so.

That or I could just tweet some fake news at him.

Sadly, in the court of public opinion, that would probably be enough to win the argument. But that's not my fault; it's the fault of all those people who believe me. Don't penalize creative people exercising their gifts for a better economic future. Let's pull the plank out of our own eye before we go after the speck in someone else's. I feel like that's good advice I heard somewhere once.

If you really look at this "fake news" stuff, yeah there's some talk that it's being secretly funded by foreign governments to mess with US elections, but for the most part, it's a product of economic disparity in a globalized world. Most of this stuff comes from shops set up in rural Macedonia, where low-level gangsters pay school children to write (or even just copy and paste) stories about the US elections in their off hours. With the advent of online advertising, you don't need any actual substance, just a headline click-baity enough to draw interest. People get paid for the eyeballs on the ads - that's all that matters. Fake news is no different than kitten videos or clever memes - it's just content meant to make someone money.

It might be poor satire, but it's certainly inventive - well, some of it - the best fake news is genuinely creative and clever, people make up stories that other people want to read. We live in a world where almost everyone universally doubts the bias of the press, even historic, well-established journalistic brands - even if a fake news site bills itself as real news, people are conditioned not to trust media. Heck, even fake news sites like the Onion that are overtly up-front about the fakeness of their news still end up getting retweeted by actual elected officials.

The problem is not some masquerading pseudo-journalist who's really a fourth grader in Gostivar (look it up); the problem is us. The great Western Individualism that we've come to know and love (and claim is the reason much of those who hate us hate us) has led us to be self-absorbed egotists, assuming that our common sense is the closet approximation to truth. We're also lazy. It doesn't take much in this internet age to research a story and then utilize that profound common sense with, you know, a basic level of information. It's the same internet these fake news sites mine to figure out what stories we might click on and then provide them to us.

If you listen to any of the numerous reporting pieces on fake news, you can hear interviews with these kids and their bosses. They're not interested in shaping US policy (although they take pride in the fact that they are), they just want to make money. If people click on Trump stories, they'll write Trump stories. It's industrious and inventive and intelligent - all things you need to be to avoid falling for this kind of news.

I hear all this hand-wringing from people lamenting the place fake news held in the recent election and I've heard nothing about the responsibility of a society to educate its people and motivate them to perform basic functions. It's not like you have to drive down to some college library to look up economic charts from the past five years - you type a couple words into google and you click on a few "about us" tabs and then you click on google a few more times to verify the information you're finding.

Yeah, it's not perfect, but the more information one has the better capable we are of making real, informed choices. Not doing the work to be informed is our fault, not someone else's.

I love fake news. If I'd had time and a little more internet marketing savvy, it sounds like a fun way to make some money. I like writing. I'm pretty creative. I'm pretty knowledgeable about the political landscape. I bet I'd be really good at it. About ten years ago, when I had a break from grad school, I'd go onto Yahoo Answers and write long, details answers to questions that were entirely false. For example, one girl was trying to get help with her homework on Romeo and Juliet and I described in 1500 words, the plot of A Streetcar Named Desire (I just used the names Romeo and Juliet instead of Stanley and Stella).

There's really no excuse for believing something just because it sounds good. I imagine it has to do with our aversion to suffering - we only work as much as we have to work, and we try to avoid it as much as possible. Talk to a middle school teacher sometime - one of the most difficult things to teach is research - good research - it's too easy to get into a mindset of "it says this somewhere" and "their opinions is as valid as anyone else's." I don't disagree with the opinion part, but there's a certain level of knowledge that's assumed. Opinions are equally valid when they come from the same level of knowledge. My opinions on the origin of black holes is not nearly as valid as that of Neil DeGrasse Tyson. If I were ever going to disagree with him, I'd have to do a lot of actual work to gain the kind of knowledge I'd need to do so.

That or I could just tweet some fake news at him.

Sadly, in the court of public opinion, that would probably be enough to win the argument. But that's not my fault; it's the fault of all those people who believe me. Don't penalize creative people exercising their gifts for a better economic future. Let's pull the plank out of our own eye before we go after the speck in someone else's. I feel like that's good advice I heard somewhere once.

Thursday, December 01, 2016

The Cross and the Idol

One of the revolutionary things about this YHWH who rescued God's people from slavery, led them through the wilderness, and secured for them a land and a future was that YHWH was always present. Even before what we Christian term "the incarnation," God was incarnated among the Hebrews. God was with them. It's why, when we read the famously accommodated prophesy about Immanuel, we don't have to claim it's foretelling a specific future about a baby in a manger, but that it's describing a constant reality: God is with us. God is present.

Part of the problem in Israel was that they took a God who could not be contained and made a box, called a temple. Pretty quickly, as you might imagine, the God who infused and inhabited all things was confined to the religious. Instead of life being worship in all of its minutia, worship became something people did in a specific place, at a specific time, in a specific way. Oh there was always rituals, but they were rituals pointing and imaging the everyday actions of the people. And no, there's no reason why religion can't still be practiced in that way (and is!), but you have to admit it's a lot easier to keep religion in a corner when the God at the center of it is wrapped up in a neat little box.

This is why it was so necessary for God to be re-incarnated - to show up in a living, breathing person - to explode back into the world that God's people had pushed God out of. No longer would God be segregated to the temple, but would be active and alive in the world. It's no wonder that Jesus seemed to reject the trappings of the temple and the religious system that had built up around it over the intervening years: there were more important things to do. Life was to be lived - lived in the way it had been created to be enjoyed. In Jesus we see a person fully inhabiting his personhood, humanity being truly human - even to the point of giving up that humanity for the sake of others.

What did we do then? Well, for a while we lived into that example. There were lots of people sacrificing and going to their deaths out of love for neighbor and enemy alike. That tradition continues; let's not say it's faded away. But what it means to be Christian, in general, over time, has faded away. We've taken that great sacrifice of love and imaged it - imbuing meaning and honor on the instrument of Christ's death and giving it pride of place in our sanctuaries.

Again, I am not arguing that the cross is misplaced or ill-used or inappropriate. For certainly the reminder of death is key to our lives as God intended them. What is most important is not blessing or survival, but sacrifice - the meaning of life is to give it away in whatever manner we are called. Love, of course, but how much love? The cross reminds us there is no limit to such love.

But we've still contained it in a box. Yes, we may wear it on a chain around our necks or tattoo it on our calves or adorn it on our clothes, but for all practical purposes we've locked it up tight in our houses of worship just as Samuel did all those many years ago. It's a method of control, for one - when God is in our box, we decide how and when and where people experience and respond to God. There's safety and security in that - the same kinds of things the cross challenges us to forsake.

This domestication is also a means of ignoring the creative purpose of our lives: to live freely and wholly into God's future. When the cross is locked up in the church, we can relegate the Kingdom to that place and time we choose to think of it. We no longer have to infuse our lives with the radical, counter-cultural otherness that so characterized the one who died upon that cross, the one who rescued a people from slavery and lived among them as they wandered, poor and helpless in the desert. We can abandon the call of God to be humble when we've made the symbol of that God to important.

That's the catch, though, isn't it. God first told God's people not to make images of worship. We brush off the Muslim desire to keep their God and prophet unseen, but forget that our tradition has the same command. Yes, we're a bit more of a gracious people, at least in paper, but the teaching is the same: do not make idols - images that depict God - because God has made the only image necessary: us. Christ, as Paul says, the very image of the invisible God, is humanity as it was intended. We are God's image. We do not have the right to make another, simply because it better serves our purpose.

The cross is a call for our lives to embrace God's purpose. We must take it up and lay it down in service of God's radical love, not our own convenient agenda. It is not an excuse to make one place sacred and another secular. It is not permission to lie and steal and cheat in our everyday lives, because something better exists in another world. Something better exists, alright, but it's not in another world, it's in the world God created this one to become.

The means by which God is transforming the world God created into the world God intended is love. The path that transformation takes is through our lives and witness, not through our religious rituals and houses of worship. That shouldn't demean or diminish the importance of those things in our lives, but it does radically alter the way we view the cross. It is not an image to be exalted and looked up, but one to be shouldered and carried.

Carried out of the boxes we have created for it and into the world where it - and we - were meant to really live.

Part of the problem in Israel was that they took a God who could not be contained and made a box, called a temple. Pretty quickly, as you might imagine, the God who infused and inhabited all things was confined to the religious. Instead of life being worship in all of its minutia, worship became something people did in a specific place, at a specific time, in a specific way. Oh there was always rituals, but they were rituals pointing and imaging the everyday actions of the people. And no, there's no reason why religion can't still be practiced in that way (and is!), but you have to admit it's a lot easier to keep religion in a corner when the God at the center of it is wrapped up in a neat little box.

This is why it was so necessary for God to be re-incarnated - to show up in a living, breathing person - to explode back into the world that God's people had pushed God out of. No longer would God be segregated to the temple, but would be active and alive in the world. It's no wonder that Jesus seemed to reject the trappings of the temple and the religious system that had built up around it over the intervening years: there were more important things to do. Life was to be lived - lived in the way it had been created to be enjoyed. In Jesus we see a person fully inhabiting his personhood, humanity being truly human - even to the point of giving up that humanity for the sake of others.

What did we do then? Well, for a while we lived into that example. There were lots of people sacrificing and going to their deaths out of love for neighbor and enemy alike. That tradition continues; let's not say it's faded away. But what it means to be Christian, in general, over time, has faded away. We've taken that great sacrifice of love and imaged it - imbuing meaning and honor on the instrument of Christ's death and giving it pride of place in our sanctuaries.

Again, I am not arguing that the cross is misplaced or ill-used or inappropriate. For certainly the reminder of death is key to our lives as God intended them. What is most important is not blessing or survival, but sacrifice - the meaning of life is to give it away in whatever manner we are called. Love, of course, but how much love? The cross reminds us there is no limit to such love.

But we've still contained it in a box. Yes, we may wear it on a chain around our necks or tattoo it on our calves or adorn it on our clothes, but for all practical purposes we've locked it up tight in our houses of worship just as Samuel did all those many years ago. It's a method of control, for one - when God is in our box, we decide how and when and where people experience and respond to God. There's safety and security in that - the same kinds of things the cross challenges us to forsake.

This domestication is also a means of ignoring the creative purpose of our lives: to live freely and wholly into God's future. When the cross is locked up in the church, we can relegate the Kingdom to that place and time we choose to think of it. We no longer have to infuse our lives with the radical, counter-cultural otherness that so characterized the one who died upon that cross, the one who rescued a people from slavery and lived among them as they wandered, poor and helpless in the desert. We can abandon the call of God to be humble when we've made the symbol of that God to important.

That's the catch, though, isn't it. God first told God's people not to make images of worship. We brush off the Muslim desire to keep their God and prophet unseen, but forget that our tradition has the same command. Yes, we're a bit more of a gracious people, at least in paper, but the teaching is the same: do not make idols - images that depict God - because God has made the only image necessary: us. Christ, as Paul says, the very image of the invisible God, is humanity as it was intended. We are God's image. We do not have the right to make another, simply because it better serves our purpose.

The cross is a call for our lives to embrace God's purpose. We must take it up and lay it down in service of God's radical love, not our own convenient agenda. It is not an excuse to make one place sacred and another secular. It is not permission to lie and steal and cheat in our everyday lives, because something better exists in another world. Something better exists, alright, but it's not in another world, it's in the world God created this one to become.

The means by which God is transforming the world God created into the world God intended is love. The path that transformation takes is through our lives and witness, not through our religious rituals and houses of worship. That shouldn't demean or diminish the importance of those things in our lives, but it does radically alter the way we view the cross. It is not an image to be exalted and looked up, but one to be shouldered and carried.

Carried out of the boxes we have created for it and into the world where it - and we - were meant to really live.

Tuesday, November 29, 2016

The Most Wonderful Time of the Year

Advent is my favorite season of the year. I think it comes from my own psychological baggage. I’ve always felt deeply empty – my therapist might encourage me to say worthless. Oh I know I’m a beloved child of God and I’m not out there looking for abuse or anything. I know who I am; I just don’t always feel it.

I heard Ian Morgan Cron speak to Olivet Nazarene University chapel recently – he talked specifically about this lack, this need, this inner sense of emptiness. He called it a universal piece of the human condition and that made me feel better. Perhaps I’m not as alone or unusual as I might’ve thought. I suppose a sanctified Nazarene elder such as myself shouldn’t still be struggling with issues of worth and purpose, but here I am and I don’t think I’m alone.

That’s exactly why I like Advent. Advent is the season that provides impetus for Christmas. Christmas is the celebration of incarnation, of Christ coming to Earth as a cute little baby boy. But that begs the question: why? Love, of course - it’s always love - but more specifically why do we need the kind of amazing sacrificial godly love we see in the birth of Christ?

It’s because we’re in such a sorry spot.

The world is pretty messed up most of the time, and we, the people of God, are far too often in the middle of it. There is pain and violence and abuse and war, depression and divorce and greed and selfishness – and there’s just as much of it in the Church as there is outside. We’re all terribly inadequate, yet deserving of so much more.

It’s that distance, that great divide between who we are and who we are created to be that Christ comes to bridge. That’s Christmas. Advent is about measuring the gap and affirming its impossibility. In Advent we mourn, we lament, we confess, and we beg.

We mourn the great potential of God’s creation and the ways in which we’ve helped to mess it up. We lament the great terrors we human beings have wrought on the world and just how many of them have grown out of control. We confess our inadequacy to tackle even the simplest of tasks without the divine presence of God almighty. And we beg for mercy. Please, Lord, don’t let us go down with this ship!

Advent is the season where we remind each other of how far we have to go, but also of how much God loves us and the absolute, unquestionable salvation that is just around the bend. Yes, we are preparing to celebrate the coming of messiah, but also of his immanent return. We bask in the joy of God’s love – the love spoken of so eloquently in John 3:16 – but we also sit with baited breath, anticipating the culmination of the Kingdom that Christ ushered in with his presence and that we so desperately need.

I love Advent, I think, because this one time of year, in the midst of our holiness culture, there’s permission to be me. I know we like to say we’re not about sinless perfection anymore, but that idea is just such a part of our DNA its shadow always lingers. There’s an unspoken (hopefully) drive to be light years ahead of where we are. Always better. Never satisfied.

Honestly, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that… in spurts, but we need a season to escape that pressure and be faulty human beings in need of a savior. It might not sound like Advent is a time for rejoicing, what with all the confessing, mourning, and lament, but Advent can be freeing for people who feel obligated to solve all the problems of the world most of the time.

Advent is our season to give up, to recognize the futility of our strivings, and place all the responsibility on God. The early cry of Advent was maranatha, “Come, Lord,” the only prayer possible when we’re at the end of our rope, when our only hope is THE only hope. It’s true that God meets every need, but we rarely see God’s way through the darkness of our desperation.

Salvation comes in unsuspecting ways: like a baby in a manger when it feels like we need an army.

Advent prepares the way for Christmas, like Lent for Easter. We need the struggle to appreciate the miracle. We need to live in the midst of who we really are before we can approach the awesome majesty of who we’re created to be.

Don’t skip Advent. Don’t make it just four weeks of advertisement for Christmas – Walmart does enough of that for everyone. Sit in the tension of the already and the not yet. Create anticipation for the glory yet to come by recognizing the profound sadness of a world not yet complete.

And when you get to Christmas, enjoy the whole thing. Those twelve days are not just an annoying song. The wisdom of our forebears knew we needed more than just one hectic morning of wrapping paper and pajamas to fully pay off the anticipation of our sorrow. We’ll be back in the midst of the world soon enough. Sing carols on New Year’s. Say “Merry Christmas” during the Rose Bowl parade.

It’s a long year and a long life. We need Advent. We need Christmas. They help us celebrate all of who we are: complex, oft-inferior, and entirely messed up; but also beautiful, beloved, lovingly crafted creations, in the very image of God.

The world isn’t going to hell in a handbasket, but it’s ok to think that it is once in a while. That’s called Advent, and it’s my favorite season of the year.

I heard Ian Morgan Cron speak to Olivet Nazarene University chapel recently – he talked specifically about this lack, this need, this inner sense of emptiness. He called it a universal piece of the human condition and that made me feel better. Perhaps I’m not as alone or unusual as I might’ve thought. I suppose a sanctified Nazarene elder such as myself shouldn’t still be struggling with issues of worth and purpose, but here I am and I don’t think I’m alone.

That’s exactly why I like Advent. Advent is the season that provides impetus for Christmas. Christmas is the celebration of incarnation, of Christ coming to Earth as a cute little baby boy. But that begs the question: why? Love, of course - it’s always love - but more specifically why do we need the kind of amazing sacrificial godly love we see in the birth of Christ?

It’s because we’re in such a sorry spot.

The world is pretty messed up most of the time, and we, the people of God, are far too often in the middle of it. There is pain and violence and abuse and war, depression and divorce and greed and selfishness – and there’s just as much of it in the Church as there is outside. We’re all terribly inadequate, yet deserving of so much more.

It’s that distance, that great divide between who we are and who we are created to be that Christ comes to bridge. That’s Christmas. Advent is about measuring the gap and affirming its impossibility. In Advent we mourn, we lament, we confess, and we beg.

We mourn the great potential of God’s creation and the ways in which we’ve helped to mess it up. We lament the great terrors we human beings have wrought on the world and just how many of them have grown out of control. We confess our inadequacy to tackle even the simplest of tasks without the divine presence of God almighty. And we beg for mercy. Please, Lord, don’t let us go down with this ship!

Advent is the season where we remind each other of how far we have to go, but also of how much God loves us and the absolute, unquestionable salvation that is just around the bend. Yes, we are preparing to celebrate the coming of messiah, but also of his immanent return. We bask in the joy of God’s love – the love spoken of so eloquently in John 3:16 – but we also sit with baited breath, anticipating the culmination of the Kingdom that Christ ushered in with his presence and that we so desperately need.

I love Advent, I think, because this one time of year, in the midst of our holiness culture, there’s permission to be me. I know we like to say we’re not about sinless perfection anymore, but that idea is just such a part of our DNA its shadow always lingers. There’s an unspoken (hopefully) drive to be light years ahead of where we are. Always better. Never satisfied.

Honestly, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that… in spurts, but we need a season to escape that pressure and be faulty human beings in need of a savior. It might not sound like Advent is a time for rejoicing, what with all the confessing, mourning, and lament, but Advent can be freeing for people who feel obligated to solve all the problems of the world most of the time.

Advent is our season to give up, to recognize the futility of our strivings, and place all the responsibility on God. The early cry of Advent was maranatha, “Come, Lord,” the only prayer possible when we’re at the end of our rope, when our only hope is THE only hope. It’s true that God meets every need, but we rarely see God’s way through the darkness of our desperation.

Salvation comes in unsuspecting ways: like a baby in a manger when it feels like we need an army.

Advent prepares the way for Christmas, like Lent for Easter. We need the struggle to appreciate the miracle. We need to live in the midst of who we really are before we can approach the awesome majesty of who we’re created to be.

Don’t skip Advent. Don’t make it just four weeks of advertisement for Christmas – Walmart does enough of that for everyone. Sit in the tension of the already and the not yet. Create anticipation for the glory yet to come by recognizing the profound sadness of a world not yet complete.

And when you get to Christmas, enjoy the whole thing. Those twelve days are not just an annoying song. The wisdom of our forebears knew we needed more than just one hectic morning of wrapping paper and pajamas to fully pay off the anticipation of our sorrow. We’ll be back in the midst of the world soon enough. Sing carols on New Year’s. Say “Merry Christmas” during the Rose Bowl parade.

It’s a long year and a long life. We need Advent. We need Christmas. They help us celebrate all of who we are: complex, oft-inferior, and entirely messed up; but also beautiful, beloved, lovingly crafted creations, in the very image of God.

The world isn’t going to hell in a handbasket, but it’s ok to think that it is once in a while. That’s called Advent, and it’s my favorite season of the year.

Thursday, November 17, 2016

Visual Comfort Food

Disclaimer #1: Basketball season has begun and thus my often regular blog posts may becomes less regular. I am doing more this year than last (both within and outside the basketball world), so it might be harder to keep the twice weekly schedule.

Disclaimer #2: My recollections here are the impressions of a ten year old, filtered through a quarter century of memory. Please do not use them to judge anyone as they are very likely wrong and almost certainly inaccurate.

That being said, I've found myself really liking the NBC sit-com Superstore. I know, I know, with all the great TV being made right now, why would you spend time with what has to be the most traditional, uninspiring, predictable show on NETWORK TV? Short answer: it's funny. Yes, it's a very cliched premise: a bunch of diverse people work at a Wal-mart stand-in; chaos ensues. It's a traditional workplace comedy - the show is about the characters and their interactions more than it's about any actual thing. The lives of the characters outside the store occasionally enter the story-line, but only as out-of-place intruders that must be dealt with.

I'm not going to make this post about how Superstore has some deeper meaning and overarching lesson for today's society. It is everything you feared it would be - it's typical; it's traditional; it's a set-up you've seen a hundred times before. One difference, though: it's funny. Really funny. The writing is clever and they make sure to pack every episode with two or three interstitial three second scenes where something funny, yet also believable happens in the store with none of the main characters involved. It's inventive within a very rigid box and I appreciate the creativity. It's also super well written (did I mention that?). The jokes are funny. I chuckle A LOT - which is saying something.

All of that to say, one of the best performances (as one might expect) is Kids in the Hall and SNL alum Mark McKinney, who plays Glenn, the store manager. His character is a take off on conservative Christians, with a little mormon love thrown in there. It would be easy for the performance to be hackey; a boss used for mockery and as a comic foil is pretty typical of these typical network shows. Glenn, though, has heart. He's a real person who doesn't at all fit a stereotype (even as the show tends to play into and then subvert typical sit-com stereotypes - dammit, I did end up making the case that there's more to this show than appears on the surface - honestly that was not my intention; I promise).

What I like about Glenn is how comfortable he is to me. I realized this morning that Glenn is like the evangelical Christians I knew growing up, before they were co-opted by the Republican party. He's religiously devout and morally ultra-conservative (in one episode he buys all the store's "morning after" pills to keep them from being used, but then has to sell them from a card table at the front of the store when he realizes how expensive they are and can't return them), but he's not hardened or ideological. Glenn loves people. All people, in every situation, and he repeatedly works to compromise between his deeply-felt convictions and his love for other people.

This is the environment in which I grew up. We were political, only in so far as abortion was concerned. A one-issue community, for the most part. I'm sure people cared about tax policy and whatever else, but none of those things were tied up in their faith. Morality was important (and it is actually important), but in the context of loving and caring for people. I grew up in a worshiping congregation that routinely welcomed people who were left out in the larger world and loved them not only into community, but into a better story for their own lives. When I say routinely, I can think of a half dozen people in a second and probably three times that if I sat down intentionally.

I thought of Glenn this morning at random, but I realized he perfectly embodies that thing so many conservative Christians are known for these days: he is "love the sinner, hate the sin." The guy's got integrity and purpose - he has views that he's pretty up-front about, but never in the context of condemnation. He doesn't disprove of some mistake or choice a friend has made in the moment - he just think the best of everyone and tries to help.

Yeah, it's just a sit-com. It's not a life lesson. But certainly the things we watch shape us in some way - that's why we like deep story and creativity. Superstore is really none of those things, but it does speak deeply to how people who are profoundly different can also be united in common cause. There's no big message there, but it's funny and comforting and well made.

That's all I wanted to say.

Disclaimer #2: My recollections here are the impressions of a ten year old, filtered through a quarter century of memory. Please do not use them to judge anyone as they are very likely wrong and almost certainly inaccurate.

That being said, I've found myself really liking the NBC sit-com Superstore. I know, I know, with all the great TV being made right now, why would you spend time with what has to be the most traditional, uninspiring, predictable show on NETWORK TV? Short answer: it's funny. Yes, it's a very cliched premise: a bunch of diverse people work at a Wal-mart stand-in; chaos ensues. It's a traditional workplace comedy - the show is about the characters and their interactions more than it's about any actual thing. The lives of the characters outside the store occasionally enter the story-line, but only as out-of-place intruders that must be dealt with.

I'm not going to make this post about how Superstore has some deeper meaning and overarching lesson for today's society. It is everything you feared it would be - it's typical; it's traditional; it's a set-up you've seen a hundred times before. One difference, though: it's funny. Really funny. The writing is clever and they make sure to pack every episode with two or three interstitial three second scenes where something funny, yet also believable happens in the store with none of the main characters involved. It's inventive within a very rigid box and I appreciate the creativity. It's also super well written (did I mention that?). The jokes are funny. I chuckle A LOT - which is saying something.

All of that to say, one of the best performances (as one might expect) is Kids in the Hall and SNL alum Mark McKinney, who plays Glenn, the store manager. His character is a take off on conservative Christians, with a little mormon love thrown in there. It would be easy for the performance to be hackey; a boss used for mockery and as a comic foil is pretty typical of these typical network shows. Glenn, though, has heart. He's a real person who doesn't at all fit a stereotype (even as the show tends to play into and then subvert typical sit-com stereotypes - dammit, I did end up making the case that there's more to this show than appears on the surface - honestly that was not my intention; I promise).

What I like about Glenn is how comfortable he is to me. I realized this morning that Glenn is like the evangelical Christians I knew growing up, before they were co-opted by the Republican party. He's religiously devout and morally ultra-conservative (in one episode he buys all the store's "morning after" pills to keep them from being used, but then has to sell them from a card table at the front of the store when he realizes how expensive they are and can't return them), but he's not hardened or ideological. Glenn loves people. All people, in every situation, and he repeatedly works to compromise between his deeply-felt convictions and his love for other people.

This is the environment in which I grew up. We were political, only in so far as abortion was concerned. A one-issue community, for the most part. I'm sure people cared about tax policy and whatever else, but none of those things were tied up in their faith. Morality was important (and it is actually important), but in the context of loving and caring for people. I grew up in a worshiping congregation that routinely welcomed people who were left out in the larger world and loved them not only into community, but into a better story for their own lives. When I say routinely, I can think of a half dozen people in a second and probably three times that if I sat down intentionally.

I thought of Glenn this morning at random, but I realized he perfectly embodies that thing so many conservative Christians are known for these days: he is "love the sinner, hate the sin." The guy's got integrity and purpose - he has views that he's pretty up-front about, but never in the context of condemnation. He doesn't disprove of some mistake or choice a friend has made in the moment - he just think the best of everyone and tries to help.

Yeah, it's just a sit-com. It's not a life lesson. But certainly the things we watch shape us in some way - that's why we like deep story and creativity. Superstore is really none of those things, but it does speak deeply to how people who are profoundly different can also be united in common cause. There's no big message there, but it's funny and comforting and well made.

That's all I wanted to say.

Tuesday, November 15, 2016

Policy over People

I've struggled to write this post. I've re-written it entirely at least three times. I even posted it once, very briefly and then took it down because it didn't quite say what I wanted to say. I'm not sure if it does now.

It's been a week since the election. The first day or two were terribly emotional - that's how people react, both positively and negatively. There's been a lot of negative. People aren't coming together the way the United States typically does in these times. I've spent a sizeable chunk of the last week talking with upset people, hurting people, angry people. What I have to say are my words and they are knowingly filtered through the reality that I am an educated, straight, white man. While I can't understand all of what many around me are going through, I do see what they are going through and feel the need to say something.

If you think it's the wrong thing or the wrong time or I'm the wrong person, I apologize; you are very likely correct.

With regards to this election, there are real two levels of upset that don't seem to be speaking to each other. People who held their noses and voted for Trump (those who did so happily and with glee can really stop reading; this is not for you) have often said, "he's not going to do the things he said he would," but that misses the point. That statement is one of policy and policy is not at the root of the anger and discontent.

Don't get me wrong, people who don't like Donald Trump's ideas are apoplectic. He wants to build a wall, perhaps limit who can enter the country in ways some find unconstitutional. He has a tax plan that benefits the rich over the poor and expands the deficit with some vain hope that the third time's the charm for disproven economic theory. People don't like his suggestions for the Supreme Court, for the Cabinet, for how to handle his own personal conflicts of interest.

But in the end, those are just policy decisions. It's not like he's the first politician to suggest any of them. He's not. Not even close. People are upset about that, the same way those on the losing side of any election rue the future their now-empowered opponent will bring about. If this were a typical election, "get over it" would be the call of the day - and it would be appropriate. In a Democracy, the people speak, even if a majority of them spoke in a different direction. The system is not fair, but it is universally unfair.

People might be upset about the things Trump said he would do (even if you believe he won't do them), but people are hurt by the things he said - about women, about minority groups, about the disabled: about people. Trump took aim at all sorts of people and even if he was singling out one woman or one disabled reporter or one particular group of immigrants, many, many, many people saw themselves in those abusive remarks.

People did not see Donald Trump as just some guy with policies they dislike (in fact, a surprising number of hurt people I've talked to this week don't much mind many of his policies), but as a guy who's a mean, abusive, cruel, sexist bully - not a person they can respect, even if they agree with his policies. Too many times I've heard someone say, "I can't believe my mom/brother/friend would choose the Supreme Court/abortion/taxes over me." For the hurting people out there, this election was not political, but personal (even beyond the ways proposed policies might personally impact people).

I understand that those people who voted for Trump did so largely for reasons of policy. Whether is was the Supreme Court or abortion or taxes or corruption, most of the Trump votes were votes for some policy that is more likely to happen with him than with Hillary Clinton. I think those angry friends and relatives out there understand those things, too (even if they disagree with you on them) But, as I said, this is not the issue. In the end, I don't really care what you think about any of these things; I might disagree with you on some of them, but they're not worth getting angry about or damaging friendships over.

What is more difficult to stomach, though, is that people I love and care about found these things, particular issues, policy, so important that it was worth overlooking the vile nature of Trump's words and actions - and, perhaps worse, his patent refusal to apologize for them. Even after the election his justified those words with his victory - as if any means of achieving a desired end are good if they succeed.

No ends, no matter how good, righteous, holy, or important, mean enough to justify the means, if the means are Donald Trump.

That's the quandary. That's the divide which people must now bridge if there is any chance in calming the storm or finding unity. It is NOT about what policy you might approve of that I don't - it's about the guy you voted for to get those policies enacted. As I said, I'm the educated, white male in this room - the outrage is only mine by proxy.* I don't have the deep seated personal hurt that so many women and people of color feel right now.

To me this great pain is a sad illustration of what I've been saying and writing all along - we take this process far too seriously. It's not that elections and governments can't be avenues for us to live well in the world and take care of each other, but they MUST NOT become the only way by which we see paths to do this. Real relationships are in jeopardy - both because some people overlooked serious moral and ethical deficiencies in the name of progress, but also because some people have put such (false) hope and faith in the goodness of this nation that their worth was wrapped up in election results.

That is not to say people shouldn't be mad or hurt, that relationships shouldn't be strained by this election, but that we must be committed to working through them with honesty and humility.

There is an argument that Hillary Clinton is no paragon of virtue - and that may be true - but I don't see people upset that someone didn't vote for Clinton, simply that people did vote for Trump. Whether those votes were in spite of his nasty rhetoric, they enabled it and piled hurt upon the people hurt by it. God may have no hierarchy of sins, but the consequences of such are simply not the same. Lying and corruption are not the same as misogyny and assault - they're just not. They have a different bearing on our relationships with each other.**

Another response is that Clinton's policies would be so corrupt and morally bankrupt that she had to be stopped at all cost. That argument is one of policy and while it might be a good one on its own merits, it skirts the real issue of hurt and harm - because we've seen what "at all cost" actually costs. It costs the emboldening of the alt-right and their white supremacist brethren. It costs fear and abuse for women and minorities across the country. While we can be unified in our opposition to such results (and, as I've said, Trump voters especially need to be more vocal and more frequent denouncers of such things), there is hard work to overcome the very real (if unintended) support a Trump vote gave to these people. "At any cost" has a face and it's a familiar one to many of us: wives, mothers, daughters, friends.

That hurt is real and it's not going away.

It's perfectly acceptable to say "wait and see" or "give him a chance" when it comes to policy. That's the rhetoric we're hearing from all sides and, honestly, I think most of your friends and family who are upset can come around to that idea. The policy stuff hurts, but it'll pass. But those hatemongers showed up within minutes of the election - emboldened by the words of our President-elect (not to mention his subsequent appointment of one of their champions to his White House staff). Donald Trump may say, "stop hurting people," but he's yet to denounce the views represented in these hateful crimes, the same views he espoused on the campaign trail and refused numerous opportunities to take back.

I get that people can't be entirely divorced from policy, 1) because policy is intrinsically linked to words and attitudes, and 2) because people really believe in the ultimate value of the policies they support. I do make the distinction, though, because we must understand each other if there is any hope of peace and reconciliation.

If there's anyway forward we must be able to listen to each other - to hear why some policy was worth electing Trump and to hear why no policy could ever be worth it. As much as we don't like it, we should probably also admit how easily we could be on the other side of this divide, how utterly simple it is to overlook personal failings for what we believe to be a greater good, and how easy it is to demonize someone for it.

That doesn't remove responsibility, though. Its not that your friends and neighbors think you're a racist or a sexist, but people felt personally attacked and when the people they loved had the opportunity to defend them with their votes, they didn't; they chose policy over people. There are consequences to our actions that cannot be covered up with good intentions. When we've hurt people we love, we cannot minimize those feelings. We can't say, "I didn't mean to" or "I meant something different," because even if those things are true, the hurt still happened and it has to be acknowledged in order to heal. I suspect the President-elect will be learning that lesson along with his supporters in the weeks and months to come.

I hope the cost of this victory is not too much for our society and our relationships to bear.

*I'm disappointed in this election for sure - and I resonate with many of the things I outline here, but I'm not surprised by this election. I'm saddened that my tribe, evangelical Christians turned out with a record percentage for Donald Trump, but I've spent my adult life dealing with theology and studying scripture. It's no surprise that the people of God choose power over patience; it's always been that way. What breaks my heart are the people, many of whom I love, for whom this reality is just now dawning. This post is not about me, but I feel I have to say something.

**And if you need proof: ask yourself if you feel towards your Clinton-supporting friends the way they feel towards you. It's not just a personal failing that correlates perfectly with voting record or results. Both sides of the comparison may be rotten, and they may be equally bad when it comes to policy, but with regards to people, it's rotten apples vs rotten oranges.

It's been a week since the election. The first day or two were terribly emotional - that's how people react, both positively and negatively. There's been a lot of negative. People aren't coming together the way the United States typically does in these times. I've spent a sizeable chunk of the last week talking with upset people, hurting people, angry people. What I have to say are my words and they are knowingly filtered through the reality that I am an educated, straight, white man. While I can't understand all of what many around me are going through, I do see what they are going through and feel the need to say something.

If you think it's the wrong thing or the wrong time or I'm the wrong person, I apologize; you are very likely correct.

With regards to this election, there are real two levels of upset that don't seem to be speaking to each other. People who held their noses and voted for Trump (those who did so happily and with glee can really stop reading; this is not for you) have often said, "he's not going to do the things he said he would," but that misses the point. That statement is one of policy and policy is not at the root of the anger and discontent.

Don't get me wrong, people who don't like Donald Trump's ideas are apoplectic. He wants to build a wall, perhaps limit who can enter the country in ways some find unconstitutional. He has a tax plan that benefits the rich over the poor and expands the deficit with some vain hope that the third time's the charm for disproven economic theory. People don't like his suggestions for the Supreme Court, for the Cabinet, for how to handle his own personal conflicts of interest.

But in the end, those are just policy decisions. It's not like he's the first politician to suggest any of them. He's not. Not even close. People are upset about that, the same way those on the losing side of any election rue the future their now-empowered opponent will bring about. If this were a typical election, "get over it" would be the call of the day - and it would be appropriate. In a Democracy, the people speak, even if a majority of them spoke in a different direction. The system is not fair, but it is universally unfair.

People might be upset about the things Trump said he would do (even if you believe he won't do them), but people are hurt by the things he said - about women, about minority groups, about the disabled: about people. Trump took aim at all sorts of people and even if he was singling out one woman or one disabled reporter or one particular group of immigrants, many, many, many people saw themselves in those abusive remarks.

People did not see Donald Trump as just some guy with policies they dislike (in fact, a surprising number of hurt people I've talked to this week don't much mind many of his policies), but as a guy who's a mean, abusive, cruel, sexist bully - not a person they can respect, even if they agree with his policies. Too many times I've heard someone say, "I can't believe my mom/brother/friend would choose the Supreme Court/abortion/taxes over me." For the hurting people out there, this election was not political, but personal (even beyond the ways proposed policies might personally impact people).

I understand that those people who voted for Trump did so largely for reasons of policy. Whether is was the Supreme Court or abortion or taxes or corruption, most of the Trump votes were votes for some policy that is more likely to happen with him than with Hillary Clinton. I think those angry friends and relatives out there understand those things, too (even if they disagree with you on them) But, as I said, this is not the issue. In the end, I don't really care what you think about any of these things; I might disagree with you on some of them, but they're not worth getting angry about or damaging friendships over.

What is more difficult to stomach, though, is that people I love and care about found these things, particular issues, policy, so important that it was worth overlooking the vile nature of Trump's words and actions - and, perhaps worse, his patent refusal to apologize for them. Even after the election his justified those words with his victory - as if any means of achieving a desired end are good if they succeed.

No ends, no matter how good, righteous, holy, or important, mean enough to justify the means, if the means are Donald Trump.

That's the quandary. That's the divide which people must now bridge if there is any chance in calming the storm or finding unity. It is NOT about what policy you might approve of that I don't - it's about the guy you voted for to get those policies enacted. As I said, I'm the educated, white male in this room - the outrage is only mine by proxy.* I don't have the deep seated personal hurt that so many women and people of color feel right now.

To me this great pain is a sad illustration of what I've been saying and writing all along - we take this process far too seriously. It's not that elections and governments can't be avenues for us to live well in the world and take care of each other, but they MUST NOT become the only way by which we see paths to do this. Real relationships are in jeopardy - both because some people overlooked serious moral and ethical deficiencies in the name of progress, but also because some people have put such (false) hope and faith in the goodness of this nation that their worth was wrapped up in election results.

That is not to say people shouldn't be mad or hurt, that relationships shouldn't be strained by this election, but that we must be committed to working through them with honesty and humility.

There is an argument that Hillary Clinton is no paragon of virtue - and that may be true - but I don't see people upset that someone didn't vote for Clinton, simply that people did vote for Trump. Whether those votes were in spite of his nasty rhetoric, they enabled it and piled hurt upon the people hurt by it. God may have no hierarchy of sins, but the consequences of such are simply not the same. Lying and corruption are not the same as misogyny and assault - they're just not. They have a different bearing on our relationships with each other.**

Another response is that Clinton's policies would be so corrupt and morally bankrupt that she had to be stopped at all cost. That argument is one of policy and while it might be a good one on its own merits, it skirts the real issue of hurt and harm - because we've seen what "at all cost" actually costs. It costs the emboldening of the alt-right and their white supremacist brethren. It costs fear and abuse for women and minorities across the country. While we can be unified in our opposition to such results (and, as I've said, Trump voters especially need to be more vocal and more frequent denouncers of such things), there is hard work to overcome the very real (if unintended) support a Trump vote gave to these people. "At any cost" has a face and it's a familiar one to many of us: wives, mothers, daughters, friends.

That hurt is real and it's not going away.

It's perfectly acceptable to say "wait and see" or "give him a chance" when it comes to policy. That's the rhetoric we're hearing from all sides and, honestly, I think most of your friends and family who are upset can come around to that idea. The policy stuff hurts, but it'll pass. But those hatemongers showed up within minutes of the election - emboldened by the words of our President-elect (not to mention his subsequent appointment of one of their champions to his White House staff). Donald Trump may say, "stop hurting people," but he's yet to denounce the views represented in these hateful crimes, the same views he espoused on the campaign trail and refused numerous opportunities to take back.

I get that people can't be entirely divorced from policy, 1) because policy is intrinsically linked to words and attitudes, and 2) because people really believe in the ultimate value of the policies they support. I do make the distinction, though, because we must understand each other if there is any hope of peace and reconciliation.

If there's anyway forward we must be able to listen to each other - to hear why some policy was worth electing Trump and to hear why no policy could ever be worth it. As much as we don't like it, we should probably also admit how easily we could be on the other side of this divide, how utterly simple it is to overlook personal failings for what we believe to be a greater good, and how easy it is to demonize someone for it.

That doesn't remove responsibility, though. Its not that your friends and neighbors think you're a racist or a sexist, but people felt personally attacked and when the people they loved had the opportunity to defend them with their votes, they didn't; they chose policy over people. There are consequences to our actions that cannot be covered up with good intentions. When we've hurt people we love, we cannot minimize those feelings. We can't say, "I didn't mean to" or "I meant something different," because even if those things are true, the hurt still happened and it has to be acknowledged in order to heal. I suspect the President-elect will be learning that lesson along with his supporters in the weeks and months to come.

I hope the cost of this victory is not too much for our society and our relationships to bear.

*I'm disappointed in this election for sure - and I resonate with many of the things I outline here, but I'm not surprised by this election. I'm saddened that my tribe, evangelical Christians turned out with a record percentage for Donald Trump, but I've spent my adult life dealing with theology and studying scripture. It's no surprise that the people of God choose power over patience; it's always been that way. What breaks my heart are the people, many of whom I love, for whom this reality is just now dawning. This post is not about me, but I feel I have to say something.

**And if you need proof: ask yourself if you feel towards your Clinton-supporting friends the way they feel towards you. It's not just a personal failing that correlates perfectly with voting record or results. Both sides of the comparison may be rotten, and they may be equally bad when it comes to policy, but with regards to people, it's rotten apples vs rotten oranges.

Labels:

character,

clinton,

election,

forgiveness,

morality,

relationship,

trump,

trust

Thursday, November 10, 2016

A Way Forward?

Paul Harvey told a Christmas story once on his radio program. My father uses it quite often in his Christmas Eve services; I've read it for him at least once. It's called "The Man and the Birds." The basic gist of the story is that a man stays home from Christmas Eve service because he just can't bring himself to believe in the incarnation - that God actually became human. While at home, a storm kicks up and he notices a flock of birds lost and weary in his front yard. The man has compassion on them and tries mightily to shoo them into the warm barn. Exasperated, the man wishes he could become a bird to lead the flock to safety - and the realization ignites within him this spark of faith.

I've been thinking about that story this morning, because I resonate with the desperation of the man. I'm not sure how to say this without coming off holier than thou (anyone who's read my twitter feed in the last 24 hours knows that's certainly not true), but part of claiming the title "evangelical" means one cares an awful lot about proclaimed truth. Instead of trying to herd a flock of birds into a barn, picture a man trying to guide trapped birds out of the barn to safety and freedom.

I believe with all my heart that the Kingdom of God is bigger, bolder, freer, more beautiful, and more expansive than any candidate, country, or campaign. I believe the good news of Jesus is that we don't have to get caught up in the machinations of power, choosing between flawed rulers and making due the best we can. When we're caught in this system is feels like birds bouncing back and forth between the walls of a barn they think encompasses the whole world, but is really a cage. Whatever floundering I do, waving my proverbial hands with exasperated one-liners, sub-par attempts at critique and satire, or wildly irresponsible mock presidential campaigns, is a desperate attempt to get the attention of my people who seem lost and unaware of it.

I know it makes me extreme and radical, but I do truly believe we shouldn't vote - not as Christians and at least not for President. As much as we try to hem and hedge and make excuses (and I'm just as guilty as anyone, see aforementioned twitter feed) our participation in that system is idolatry. It is a statement that the Kingdom of God is not enough for us, we must also have the kingdoms of this world.

When Dietrich Bonheoffer joined the plot to kill Adolf Hitler, he wrote, essentially, that he believed his actions were sinful and that they might earn him an eternity in hell, yet he willingly committed them anyway because he could stomach no other option. I try to take this perspective to heart when dealing with difficult issues (especially the taking of life), recognizing that we do not always possess the "right" solution in every instance. Similarly I recognize my tendency to do nothing over an imperfect something has not and does not always prove beneficial to me, my faith, or those around me.

At the same time, it feels as though Bonhoeffer's position is the only one that makes sense for Christian voters. If you're there, I might disagree, but I can understand. I just think we shouldn't be voting if we can, at all, help ourselves. There's nothing good in our preoccupation with power. It's dirty and messy and wreaks of lack of faith. We can't play pretend, saying we believe in a Kingdom ushered in by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, then invest ourselves and our future in kingdoms that operate on an entirely different foundation.

I've written this before, but I know it gets trickier on a local level - since we have to get along with our neighbors. If there weren't a town council, we'd have to invent one, right? Or maybe we really could just live sacrificially for the good of the other? Maybe I'm just as trapped in the barn as everyone else, none of us really believing the door exists, or, if we do, not really believing we can ever find it.

I don't mean not voting for one person or another, but exempting ourselves from the conversation of us vs them (or even them vs them, with some obligation to choose sides). There is just us. As much as we'd like to say we can be loyal to our first allegiance and also take sides as Republicans or Democrats, we're fooling ourselves. Those identities in some way hinder us from being who we were created to be. The same is true for our identities as American or Arabian, Ugandan or Dutch. They seem convenient, but they just get in the way. Paul said neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female (boy, is it hard to let go of that one!), and I'm even starting to wonder if even our identity as "Christians" gets in the way of our identity in Christ.

I don't think I've handled myself well in this flailing attempt to point our attention towards the door. I sure hope I've not come off as demonizing "them" who might think differently than me. My genuine desire is to caution "us" about the dangers we have embarked upon - and they are quite likely the exact same dangers we'd've encountered if 80% of us had voted the other direction.