Two weeks ago now I preached a message from Isaiah 62:1-5 about how God has not abandoned God's people - and thus we cannot abandon God's people. The importance of the Church for the redemption of the world has become a very important focus of my life and theology. It's an idea I really first encountered through a Derek Webb song ten years ago. I often use the phrase, "wherever we're going in this life, we're going to get there together or we're not going to get there at all." (I think I coined it, but my apologies if I subconsciously stole it from someone.) I really believe that God's essence is relational love and thus is the means through which we find purpose and meaning. I think it's essential.

Or do I?

After that service on the 20th, I got home and saw Twitter was all atwitter with some terrible thing Mark Driscoll said. I was about to join the fray and post a snarky comment, when that pesky conscience reminded me of the sermon I had preached that very morning. I had used the example of John Lewis reconciling with many of the racists who'd tried to kill him, as a means of illustrating that even our Christian brothers and sisters who are dead wrong don't deserve to be disowned. (I told you, the Church is a radical lady.) I just couldn't join the crowd and denounce Driscoll. I needed to think.

Luckily that week was my retreat, so it was another of many ponderings. I realized that I'd always defined "the Church" not as any institution or denomination, but as the people of God who lived faithfully in the way of Christ. I still think that's the correct definition. There's a lot of people who go to services who aren't part of the Church - and I suspect there's plenty of those who are a part of the Church without knowing it.

I've always said I love the Church. I think I mean(t) both the idea of God's faithful people and also those Christians with whom I have relationship. The people among whom I live and worship are far from perfect, but I know them and I'm committed to getting along with them. In those terms, I love the Church.

I can't say, however, I have a lot of love from people like Driscoll, who I believe is wrong in almost everything he says. I think he's been hurt somewhere along the line or his human faults have pushed him in the wrong direction. I think he's often missed the point. He isn't alone, of course, but he tends to be the poster child for such persons - and he doesn't seem to mind it.

However, in the course of my ponderings I realized that there's just no sense to my perspective on this. In choosing to define Church by faithfulness instead of attendance or self-identification, I ended up being the arbiter of who was living faithfully in the way of Christ and who wasn't.

The Church is imperfect. That's not the issue. The issue was how difficult some of those imperfections are to live with. Honestly, I imagine Mark Driscoll could say the same thing about me. I'm far from perfect, but I gladly cling to God's grace in those instances. I suppose I need to extend that same grace to other imperfect brothers and sisters (even the ones who claim to represent absolute truth).

But that doesn't make me feel any better, really. I mean, where do we draw the line? Does every person who claims faith in Jesus Christ get to be part of God's people? I think that's what scripture says, scary as that may be. Who is my brother? Is Mark Driscoll? What about Fred Phelps? Can someone spouting hateful filth, directly counter to the gospel (or my perception of the gospel) really be part of God's people?

Who gets to decide who's faithful?

I hope it's not Mark Driscoll or Fred Phelps - but God help us all if it's me.

Ultimately, though, it isn't about who's out and who's in. That's sort of the point I was making at the beginning of the post and in that sermon that messed me up so badly. We're all in - that's the beauty of grace. It doesn't mean we're all right and it can certainly mean some people are all wrong. I'm not going to sanitize the hurtful, hateful, or haphazard things people say in the name of Christ. When you look at it, we're all getting things wrong.

The real point is the way we treat one another. A wonderful old professor of mine explained the original definition of heresy as defined by the early Church - a heretic is someone who refuses to come to the table. A heretic is not someone who is kicked out of the Church, a heretic is someone who refuses to be part of the Church.

If I invalidate the faith claims of another, I am the heretic. I can't pile on Mark Driscoll with everyone else, I don't even know the guy. I can certainly critique and counter his ideas - and I'll continue to do so. But I also imagine there's a few things upon which we can agree. If we ever get the chance to talk, perhaps we'll better understand each other and, in the process, better understand this God whom we serve.

In the end, if we're not going to defend the Church from some of her inadequacies, there's really no reason to defend her from any of them. There's hope for our future - that's the claim we make and affirm; it's the reason we have faith. That doesn't mean we excuse the past or the present, but it means we can't completely condemn them either.

#hope

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Monday, January 28, 2013

Reflections on Parenthood

I made another interesting realization last week on retreat. It was the first time I'd been away from my 8 month old daughter over night. A month or two before the baby was born and during the process of hospital visits and various classes, I told my wife that if I had to choose, at some point during the birthing process, between her life and the baby's, I'd choose her.

Obviously, this is a pretty rare and awful thing to think about - but it's all too real for some people. I imagine the appropriate warnings from medical professionals, coupled with the stress of the situation led me down that path. Some people have to make that choice. At the time, it was a no brainer.

My wife and I have been married eight years. She's the only person I've ever really dated and our relationship could be described as mildly co-dependent - at least on my end. I'm a bit of an obsessive personality and I absolutely hate change. I'm not the kind of person that needs everything planned out, but if I do plan something, you better have a really, really, really good reason to ask me to change. When I married my wife, I promised to be faithful and, at least in my head, I wasn't satisfied with "until death does us part." I love her and I plan on being married to her at least until I die, regardless of whether or not she goes first.

Compared to that, the unknown unborn child she carried, just didn't seem to match up. I wasn't about to trade in someone who's become such an important part of my life for someone I've just met and, let's face it, is awfully high maintenance.

I've told people before and even since my daughter was born, that I'm not a big fan of having kids. The idea of it is not at all appealing. They take up a lot of time and limit the options you have in life. There's also an awful lot of kids in the world already who don't have anyone to take care of them. I'm just not big on the idea of having kids. Of course, now that I have one of my own - this particular child - I'm happy to keep and be inconvenienced by and waste time on.

So, this week, while being away from my wife and daughter, I found that I missed my daughter more than I missed my wife. I chalked that up to familiarity. I've been away from my wife on numerous occasions during our marriage and she's much more capable of taking care of herself. Also, my daughter has only been alive for about 200 days - so missing two of them was a whole one percent of her life.

But in the course of pondering these things (for pondering is one of the best things to do on retreat) I came to the realization that, were the same choice presented to me now - between the life of my wife or my daughter - even though it's even more awful and even less likely, I'd choose the kid.

I recognize that this might sound demeaning or less than loving towards my wife (although I doubt she'd have even spent a tenth of the time I did before making the same decision), I think a lot of the reasons for making the choice are the same.

The baby is dependent on me. My wife depends on me greatly (and I on her), but we're not dependent on each other. The baby needs a parent. While that same line of reasoning might have been a negative before hand (I still have no idea how we'd survive if it were just two of us), it is an exciting prospect now.

This little person is new. There's a whole world she'll be discovering and I get to see it again through her eyes (with the perspective of my own). That's exciting. The same familiarity that led me to choose differently a year ago, seems much more selfish now. I would have chosen my wife for my own benefit. I would miss her and my life would be better. Now, in choosing the baby, there's much more of a focus on the other.

I've never before been in a position to influence a life so greatly - and a life that will likely live on well beyond mine. Our culture and attitude is defiantly immediate, but raising children is entirely forward-looking. The way we treat children is what gets passed on to the future as a way of life. Just as those who've gone before us have handed down wisdom to help us learn from their experiences - I have some responsibility in forming a new life.

I imagine there's a bit of selfishness there, too. The idea that I have something to contribute or pass on. That my experiences will result in benefit for my children. It's certainly not a humble position. Yet there's something ingrained in all of us that parents are the best people to raise a child. I have to think there's more than just evolution involved in that idea.

Ultimately, if there were a choice to make, I hope it would be to give my life so they both could continue - and I recognize that there really is no choice. If either my wife or my daughter were missing, life would be less good, less enjoyable, less fun. I also recognize that the nature of life and of God means things would progress, even if I lost both my wife and my daughter. There would still be purpose and there would still be love and wisdom to bestow, grace to receive.

I don't think there's a point to this particular post. Just a description, an observation. Having kids changes you - and often in ways you'd never expect. It's certainly given me pause to see and experience the world more broadly.

Obviously, this is a pretty rare and awful thing to think about - but it's all too real for some people. I imagine the appropriate warnings from medical professionals, coupled with the stress of the situation led me down that path. Some people have to make that choice. At the time, it was a no brainer.

My wife and I have been married eight years. She's the only person I've ever really dated and our relationship could be described as mildly co-dependent - at least on my end. I'm a bit of an obsessive personality and I absolutely hate change. I'm not the kind of person that needs everything planned out, but if I do plan something, you better have a really, really, really good reason to ask me to change. When I married my wife, I promised to be faithful and, at least in my head, I wasn't satisfied with "until death does us part." I love her and I plan on being married to her at least until I die, regardless of whether or not she goes first.

Compared to that, the unknown unborn child she carried, just didn't seem to match up. I wasn't about to trade in someone who's become such an important part of my life for someone I've just met and, let's face it, is awfully high maintenance.

I've told people before and even since my daughter was born, that I'm not a big fan of having kids. The idea of it is not at all appealing. They take up a lot of time and limit the options you have in life. There's also an awful lot of kids in the world already who don't have anyone to take care of them. I'm just not big on the idea of having kids. Of course, now that I have one of my own - this particular child - I'm happy to keep and be inconvenienced by and waste time on.

So, this week, while being away from my wife and daughter, I found that I missed my daughter more than I missed my wife. I chalked that up to familiarity. I've been away from my wife on numerous occasions during our marriage and she's much more capable of taking care of herself. Also, my daughter has only been alive for about 200 days - so missing two of them was a whole one percent of her life.

But in the course of pondering these things (for pondering is one of the best things to do on retreat) I came to the realization that, were the same choice presented to me now - between the life of my wife or my daughter - even though it's even more awful and even less likely, I'd choose the kid.

I recognize that this might sound demeaning or less than loving towards my wife (although I doubt she'd have even spent a tenth of the time I did before making the same decision), I think a lot of the reasons for making the choice are the same.

The baby is dependent on me. My wife depends on me greatly (and I on her), but we're not dependent on each other. The baby needs a parent. While that same line of reasoning might have been a negative before hand (I still have no idea how we'd survive if it were just two of us), it is an exciting prospect now.

This little person is new. There's a whole world she'll be discovering and I get to see it again through her eyes (with the perspective of my own). That's exciting. The same familiarity that led me to choose differently a year ago, seems much more selfish now. I would have chosen my wife for my own benefit. I would miss her and my life would be better. Now, in choosing the baby, there's much more of a focus on the other.

I've never before been in a position to influence a life so greatly - and a life that will likely live on well beyond mine. Our culture and attitude is defiantly immediate, but raising children is entirely forward-looking. The way we treat children is what gets passed on to the future as a way of life. Just as those who've gone before us have handed down wisdom to help us learn from their experiences - I have some responsibility in forming a new life.

I imagine there's a bit of selfishness there, too. The idea that I have something to contribute or pass on. That my experiences will result in benefit for my children. It's certainly not a humble position. Yet there's something ingrained in all of us that parents are the best people to raise a child. I have to think there's more than just evolution involved in that idea.

Ultimately, if there were a choice to make, I hope it would be to give my life so they both could continue - and I recognize that there really is no choice. If either my wife or my daughter were missing, life would be less good, less enjoyable, less fun. I also recognize that the nature of life and of God means things would progress, even if I lost both my wife and my daughter. There would still be purpose and there would still be love and wisdom to bestow, grace to receive.

I don't think there's a point to this particular post. Just a description, an observation. Having kids changes you - and often in ways you'd never expect. It's certainly given me pause to see and experience the world more broadly.

Friday, January 25, 2013

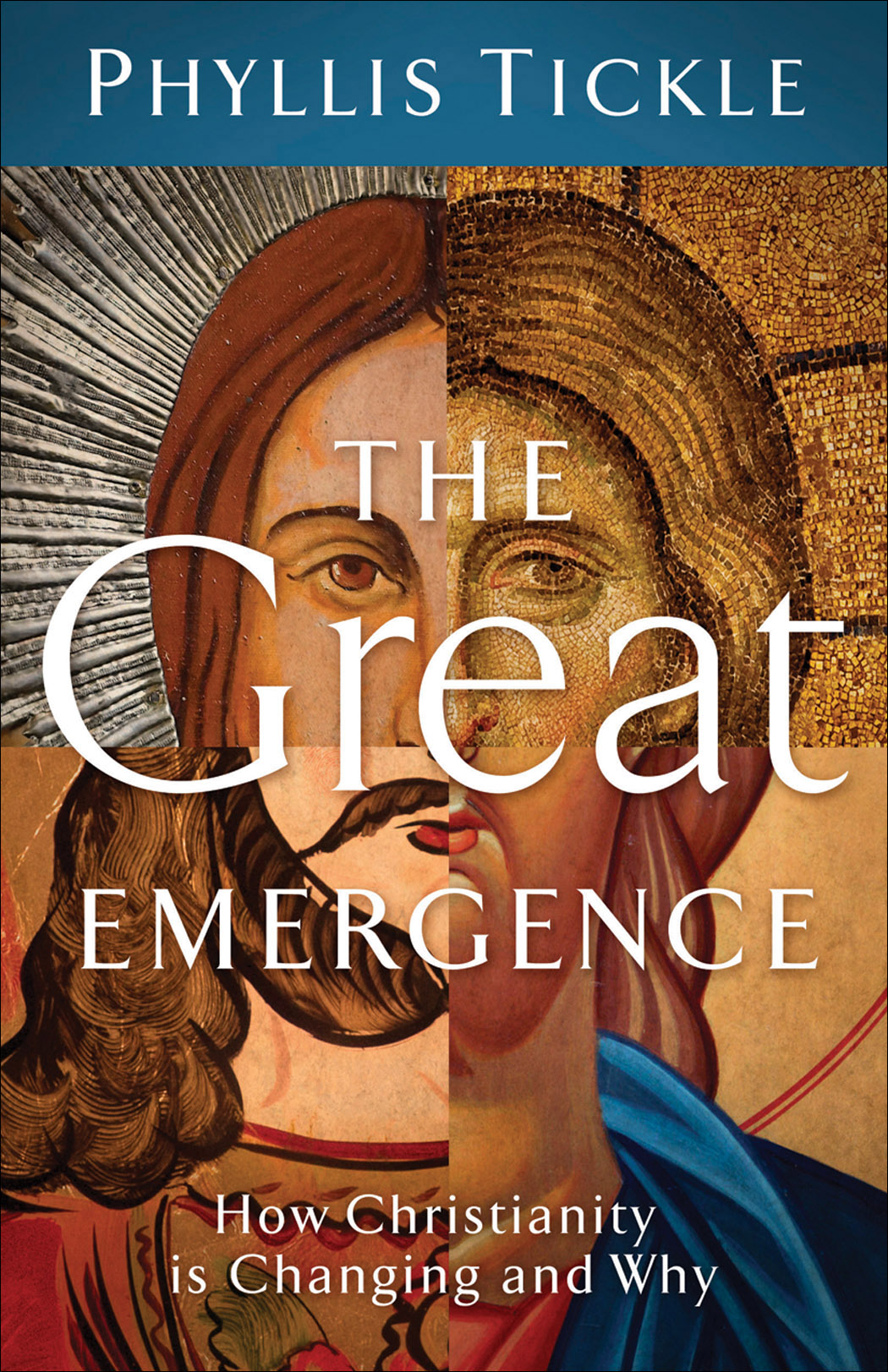

The Great Emergence

Sorry for the holiday break. It's been a busy two months. Nevertheless, I am back - and fresh off a retreat with lots of ideas and thoughts to share. One of the real benefits of the retreat is solitude. I leave my cell phone behind and try to break out of a dependence on time. I was able to read an entire book - The Great Emergence, by Phyllis Tickle - and I wanted to give a brief review.

I know I'm half a decade behind at this point, but The Great Emergence really is a profound and important book for our time. Tickle examines the current cultural/political/religious shift towards post-modernism, particularly the religious aspects, from a historical and sociological perspective. Her perspective and approach are more clinical and scientific, providing a breath of fresh air from the emergent evangelists. There is little discussion of doctrine or specific beliefs, but more an analysis and breakdown of how we believe, how belief itself changes over time, and how these changes relate to the larger world.

I found the book simple to understand and yet profound in its depth. There's a lot of mine and ponder. Perhaps her most important contribution, however, is the provision of a nomenclature for the shift. Tickle gives precise descriptions to otherwise nebulous conversations and provides an overview of a process in which so may of us find ourselves stuck in the midst. I've often had trouble orienting my own thoughts in regards to others and to religion itself because of my necessary biases and limited perspective. Tickle gives us a way to speak about what's happening around us and a firm foundation from which to speak with each other.

It's a book that anyone who finds faith important should read.

I know I'm half a decade behind at this point, but The Great Emergence really is a profound and important book for our time. Tickle examines the current cultural/political/religious shift towards post-modernism, particularly the religious aspects, from a historical and sociological perspective. Her perspective and approach are more clinical and scientific, providing a breath of fresh air from the emergent evangelists. There is little discussion of doctrine or specific beliefs, but more an analysis and breakdown of how we believe, how belief itself changes over time, and how these changes relate to the larger world.

I found the book simple to understand and yet profound in its depth. There's a lot of mine and ponder. Perhaps her most important contribution, however, is the provision of a nomenclature for the shift. Tickle gives precise descriptions to otherwise nebulous conversations and provides an overview of a process in which so may of us find ourselves stuck in the midst. I've often had trouble orienting my own thoughts in regards to others and to religion itself because of my necessary biases and limited perspective. Tickle gives us a way to speak about what's happening around us and a firm foundation from which to speak with each other.

It's a book that anyone who finds faith important should read.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)