We have this notion of greatness that keeps us from living our lives. Even those people who did great things, the trend now is to humanize them - not to take them down a peg, but to show they are real people. Think about the MLK movie that explored his affair a few years back; I hear there's a Mother Theresa movie in the works exploring the doubt she shared later in life. Yes, these heroes we exalt found themselves in usual circumstances and handled themselves remarkably well, but in the end they were just people - no different from you or me.

I think we latch onto these stories in pop culture as a way of encouraging one another. We hold up heroes and explore them as people to remind each other that we're all capable of great things. I'm not sure that practice is doing us any good - in fact, it might be doing us harm.

Oh, I think it's wonderful to explore and highlight the humanity of our heroes, but it shouldn't be to challenge us to greatness, it should be to challenge us to ordinariness. People who set out for greatness rarely achieve it, but those content to humbly focus on the life in front of them with full hearts often find themselves in the midst of great things.

Now, of course, talent will rise to the top - talented people, coupled with determination, emerge as people who get recognized, but it doesn't make them less human. They aren't superheros.

Perhaps there is a part of us that latches on to such people (or fictionalized superheroes) because we recognize a lack in us - talent, drive, determination that will likely keep us from being "top in our field." If so, then heroes become nothing but an escape, further removing us from the lives we actually lead.

I think there is some underlying drive in each of us to be superheros - we want to be separated from the rest and bathed in applause. Who wouldn't? It gets compounded by millenia of societal reinforcement, celebrating the best and brightest, smartest and strongest - we've come to just accept that some people, fitting particular categories, are just better than everyone else. They're heroes and we should aspire to be them or something like them. In reality, though, this only reinforces the position of power those labeled the heroes enjoy.

I'm not saying, "don't do great things," what I am questioning is how we define greatness. We tend to use exceptional categories, highlighting people who look least like everyone else. There is some merit there, I suppose, but it's easy to fall into the superhero trap working that way. I wonder if perhaps, as we measure greatness, the greatest thing we can do is to simply be present in your own life - and the greatness of this can only really be measured by the people around you (and can't be compared with much of anything).

Using this measure, it's easy to be exceptional, but very difficult to actually be excepted - to be singled out for larger fame. After all, they sell "World's Greatest Dad" mugs at every souvenir stand.*

How many lives get derailed by trying to be "something" - the best lawyer, the best athlete, the smartest guy in the room? When we make those things the focus of our lives, we miss out on our lives. This notion that fulfillment and satisfaction exist somewhere out there rather than right where you are is the key to doom. Peter Rollins often says, "I hope you achieve your dreams... so you can recognize they're not the answer to your problems."

This is seen no more truthfully than in the superhero myth - the notion that some people can do more and be more. It's the justification for a comparison society.* And while it seems like this only works out for those people who fare well in the comparison, we have to recognize it doesn't work so well for them either. We exalt people we admire to superhero status and in the process dehumanize them. They're no different than our super-villains - isn't that the point of these new Batman movies? No one wants to be the Joker, but we don't really want to be Batman either.

The solution is not to ignore great things; we need to see examples of real love, sacrifice, and commitment in our world. The solution is to celebrate greatness for its mundanity. Mother Theresa is all set to be St. Theresa of Calcutta here in a few months. She is a hero of mine. Her life accomplishments seem super-human, in all honesty - but if we look at her that way, we miss out on the real testimony she provides - "not great things, but small things with great love." You can be as successful in life as Mother Theresa and never get one column inch of press - you may not even be fully recognized by the members of your own family.

That's the rub, really. There are no superheroes. There are only humans. We should work to be good ones.

*There's a whole separate conversation here about comparison and how that works - clearly some people are better father's than others, but we really get into trouble when we try to rank everyone. Yes, it's easy to pick out the drunk who skips Christmas to gamble, but it's more difficult to parse rankings of greatness absent these obvious flaws. It's better to judge individuals by the needs of the relationship their in, rather than in comparison to others. Even if he's the only Dad on the planet, a drunk gambler is not going to do well on a performance review.

Tuesday, December 22, 2015

Thursday, December 17, 2015

The Real Frenemy

It's become pretty clear that part of the narrative of life in the USA right now is fear. There's a large segment of the population singing the praises of fear. We sometimes couch it in fancy rhetoric - risk-management, security, liberty, or what have you (it kind of reminds me of the classic George Carlin bit) - but it's all basically the same, "Watch out!" Whether its guns or terrorists or government intrusion, socialists or immigrants or refugees, we're told to be aware, be prepared. Watch out!

It's a fear narrative and I'm coming more and more to recognize that it's a symptom of fundamentalism - a term we most often associate with religion, but our personal security and political allegiances are basically religion at this point anyway, so it fits. The core of fundamentalism is essentially the holding of a belief as definitively true. It's associated with religion because religion is usually the place people take it most seriously - fundamental religious beliefs have to do with eternity and afterlife, which come off as pretty important things. People take them seriously.

What we see in our world today is a vocal and rabid fundamentalism couched in Islam, sure, but really more about power and control. The fundamental belief isn't really religious as much as "I think I, and people who think like me, should be in charge." Religion, as it has always historically been used, gets people excited to die for fundamentalism, but the fight is not inherently religious.

We're seeing an answer, magnified by the emotional appears and fear-mongering of an election cycle - American fundamentalism, couched in Christianity, which really says, "I, and people who think like me, should really be in charge." This is the largest battle, but as I said earlier, there's fundamentalism rearing it's head everywhere - guns are evil vs guns are blameless, social responsibility vs personal responsibility, etc.

Fundamentalists pick sides and go to war. When you've got a fundamental belief that must be true there is no other conclusion than the other guy is wrong, probably evil, certainly not worth a lick. When you have two rabid sides with this core belief the only real solution is to charge at each other and fight to the death. There is a meeting in the middle, but one that ends only with one side (or maybe no one) winning.

Compromise gets you lumped in with the enemy, the same way pacifists, for example, were ostracized and treated with suspicion in WWII. If someone doesn't see things out way, they must be misguided; it only helps the enemy.

It's funny, though, that in the midst of these pitched battles, those forces diametrically opposed to one another look so similar. Of course the what of their belief couldn't be more different (usually), but the how is identical. It's fundamentalism. This is how someone you might agree with politically or philosophically, can seem so outrageous, despite advocating things you might support. The ideas themselves are not the difference, but the way in which we hold our ideas.

It also explains how people can find commonality and camaraderie with those who differ politically or philosophically. We are drawn to people who hold ideas in the same way we hold them, even if we disagree with the ideas themselves. In our grand historical perspective we lump Fascist Hitler in with Communist Lenin, even though these two notions of government are as opposed to one another as possible - we link them because they were believed and lived out the same way in Germany and Russia - with a fundamentalist fervor.

I'd argue the counter to fundamentalism is not compromise or weakness. I believe in knowing what we believe, fundamentally, and having strong opinions. The counter to fundamentalism is holding those beliefs with a loose grip. Not that we would easily change our minds (I'd hope any thinking person spends time, you know, thinking, before arriving at conclusions), but that we'd recognize our opinions are just opinions.

This should be easy for Christians to do. We claim a universal religion, which means one that applies and draws all people. We believe God has and does reveal truth to all people at all times and faithfully searching after that revelation will lead all people to truth. Here, disagreement doesn't bring contention, but conversation, where we can seek out the fundamental points at which we disagree and attempt to understand why someone else makes a different choice or comes to a different conclusion.

Yes, I suppose there's a "danger" that the other might prove convincing, but those moments are rare (and should probably be welcomed anyway, right, if we're really after truth). More often it leads us to deeper understandings of our own positions. Somehow, by holding our beliefs lightly, the become more ingrained in our being - rather than being held to tightly we choke all life out of them.

People enjoy a good fight - it's why it's so easy to find one. If we take a fundamentalist position there will always be an opponent ready to do battle. I think this comes from a sense of comfort. We're far more comfortable with an enemy we can completely define than we are with an ally who seems somewhat mysterious. It's almost as if our enemies give us the comfort to continue believing, while our friends scare us with the possibility of unbelief.

Those whom name themselves our enemies do us no favors unless we're willing to entertain the notion that they might be right. Only then can we grow and deepen the very beliefs the other seeks to challenge.

Just some thoughts on a rainy Thursday afternoon.

It's a fear narrative and I'm coming more and more to recognize that it's a symptom of fundamentalism - a term we most often associate with religion, but our personal security and political allegiances are basically religion at this point anyway, so it fits. The core of fundamentalism is essentially the holding of a belief as definitively true. It's associated with religion because religion is usually the place people take it most seriously - fundamental religious beliefs have to do with eternity and afterlife, which come off as pretty important things. People take them seriously.

What we see in our world today is a vocal and rabid fundamentalism couched in Islam, sure, but really more about power and control. The fundamental belief isn't really religious as much as "I think I, and people who think like me, should be in charge." Religion, as it has always historically been used, gets people excited to die for fundamentalism, but the fight is not inherently religious.

We're seeing an answer, magnified by the emotional appears and fear-mongering of an election cycle - American fundamentalism, couched in Christianity, which really says, "I, and people who think like me, should really be in charge." This is the largest battle, but as I said earlier, there's fundamentalism rearing it's head everywhere - guns are evil vs guns are blameless, social responsibility vs personal responsibility, etc.

Fundamentalists pick sides and go to war. When you've got a fundamental belief that must be true there is no other conclusion than the other guy is wrong, probably evil, certainly not worth a lick. When you have two rabid sides with this core belief the only real solution is to charge at each other and fight to the death. There is a meeting in the middle, but one that ends only with one side (or maybe no one) winning.

Compromise gets you lumped in with the enemy, the same way pacifists, for example, were ostracized and treated with suspicion in WWII. If someone doesn't see things out way, they must be misguided; it only helps the enemy.

It's funny, though, that in the midst of these pitched battles, those forces diametrically opposed to one another look so similar. Of course the what of their belief couldn't be more different (usually), but the how is identical. It's fundamentalism. This is how someone you might agree with politically or philosophically, can seem so outrageous, despite advocating things you might support. The ideas themselves are not the difference, but the way in which we hold our ideas.

It also explains how people can find commonality and camaraderie with those who differ politically or philosophically. We are drawn to people who hold ideas in the same way we hold them, even if we disagree with the ideas themselves. In our grand historical perspective we lump Fascist Hitler in with Communist Lenin, even though these two notions of government are as opposed to one another as possible - we link them because they were believed and lived out the same way in Germany and Russia - with a fundamentalist fervor.

I'd argue the counter to fundamentalism is not compromise or weakness. I believe in knowing what we believe, fundamentally, and having strong opinions. The counter to fundamentalism is holding those beliefs with a loose grip. Not that we would easily change our minds (I'd hope any thinking person spends time, you know, thinking, before arriving at conclusions), but that we'd recognize our opinions are just opinions.

This should be easy for Christians to do. We claim a universal religion, which means one that applies and draws all people. We believe God has and does reveal truth to all people at all times and faithfully searching after that revelation will lead all people to truth. Here, disagreement doesn't bring contention, but conversation, where we can seek out the fundamental points at which we disagree and attempt to understand why someone else makes a different choice or comes to a different conclusion.

Yes, I suppose there's a "danger" that the other might prove convincing, but those moments are rare (and should probably be welcomed anyway, right, if we're really after truth). More often it leads us to deeper understandings of our own positions. Somehow, by holding our beliefs lightly, the become more ingrained in our being - rather than being held to tightly we choke all life out of them.

People enjoy a good fight - it's why it's so easy to find one. If we take a fundamentalist position there will always be an opponent ready to do battle. I think this comes from a sense of comfort. We're far more comfortable with an enemy we can completely define than we are with an ally who seems somewhat mysterious. It's almost as if our enemies give us the comfort to continue believing, while our friends scare us with the possibility of unbelief.

Those whom name themselves our enemies do us no favors unless we're willing to entertain the notion that they might be right. Only then can we grow and deepen the very beliefs the other seeks to challenge.

Just some thoughts on a rainy Thursday afternoon.

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

Fundamentalism, Unbelief, and the Nazarenes

I posted the observations below on Naznet last week. They got a lot more praise than I expected. I figured it would be interesting to share them more widely as see how others feel.

As regular readers of the blog (and my Facebook friends) will know, I've been reading a lot of Peter Rollins lately (I've been taking an online course he offers to work through his latest book, The Divine Magician). One of the more interesting things to me has been the way he talks about the importance of unbelief, specifically in communities with a fundamental belief.

He calls these communities Fundamentalist, but not really in the same sense we might - he simply means there's a core belief held to be fundamental to faith. His examples are: if we have enough faith, God will heal us and we don't need doctors; we are better off in the next life than this one; and any of our loved ones who don't clearly express a belief in Jesus are destined for a fiery burning hell.

His point is simply that these communities rely on unbelief to survive. Most people in them, you'll find, do consult doctors if someone breaks a leg, aren;t shooting their children to spare them the horrors of this world, and don't constantly hound their un-professed loved ones into Christian faith.

Now, this is overgeneralization, for sure, and I'd like to avoid debating the specifics on these points. It's overall idea that rings true to me - without some measure of lived doubt, these beliefs become absurd. In fact, Rollins argues the most dangerous members of these groups are the people who really do believe - their sort of irrational behavior in living out these beliefs completely show the underlying fundamental to be hollow if not horrific.

The interesting part for me, in thinking about the Church of the Nazarene, is how this doubt manifests itself in community. He talks about people on the margins feeling the doubt and trusting people closer to the center of the organization - meaning, they assume, people closer to the center of the group don't have the doubt or have less, so they're more comfortable with their own.

The problem arises as people move closer to the center - think a parishioner enters the course of study and becomes a minister, or a minister is elected DS or to some other leadership position, and so on. What they then realize is that no level of commitment to the idea can remove the doubts they have about the idea itself, and it creates a crisis.

I'll quote him here:

Just in light of all the mess that's been (and continues) going on at the center of our denomination, this really struck home. While we might not be fundamentalists, our conception of sanctification certainly holds that place pragmatically in our structure and belief. We theologically nuance things, but at the core is this notion that once we're sanctified we shouldn't be going back to old ways of doing things - sanctified people can be trusted implicitly, our leaders are people of integrity at all times, etc.

I won't argue against holiness; I believe it strongly, but there is a sense of unbelief buried deep that allows us to live with it in our everyday lives. We're learning to express it more and more, but it's going to be tough to do so honestly at the very core of our structure.

I think it's certainly healthy for us to be able to say "yes, we believe in sanctification, but the way it ends up being worked out in real life is more than a little messy." Lots of us are more comfortable doing so these days, but we don't have a structure that can support such statements and perhaps it's taking a real toll on the people we put in the middle of that structure.

I won't say any of our leaders are going through this kind of existential crisis, but in reading the Rollins quote above, it sure brought to mind the events of the last couple years (and maybe longer).

As regular readers of the blog (and my Facebook friends) will know, I've been reading a lot of Peter Rollins lately (I've been taking an online course he offers to work through his latest book, The Divine Magician). One of the more interesting things to me has been the way he talks about the importance of unbelief, specifically in communities with a fundamental belief.

He calls these communities Fundamentalist, but not really in the same sense we might - he simply means there's a core belief held to be fundamental to faith. His examples are: if we have enough faith, God will heal us and we don't need doctors; we are better off in the next life than this one; and any of our loved ones who don't clearly express a belief in Jesus are destined for a fiery burning hell.

His point is simply that these communities rely on unbelief to survive. Most people in them, you'll find, do consult doctors if someone breaks a leg, aren;t shooting their children to spare them the horrors of this world, and don't constantly hound their un-professed loved ones into Christian faith.

Now, this is overgeneralization, for sure, and I'd like to avoid debating the specifics on these points. It's overall idea that rings true to me - without some measure of lived doubt, these beliefs become absurd. In fact, Rollins argues the most dangerous members of these groups are the people who really do believe - their sort of irrational behavior in living out these beliefs completely show the underlying fundamental to be hollow if not horrific.

The interesting part for me, in thinking about the Church of the Nazarene, is how this doubt manifests itself in community. He talks about people on the margins feeling the doubt and trusting people closer to the center of the organization - meaning, they assume, people closer to the center of the group don't have the doubt or have less, so they're more comfortable with their own.

The problem arises as people move closer to the center - think a parishioner enters the course of study and becomes a minister, or a minister is elected DS or to some other leadership position, and so on. What they then realize is that no level of commitment to the idea can remove the doubts they have about the idea itself, and it creates a crisis.

I'll quote him here:

Unfortunately, its often the case that by the time someone takes his beliefs absolutely seriously and discovers their impotence, it's too difficult for him to leave. This is most obvious among religious leaders who have jobs within their institutions. For often they find the limits of their beliefs only when they are wholly dependent on their church for material support. Hence it becomes harder to leave at the very point they are most disillusioned.

This is why we often find it true that the closer we get to the inner circle of the church the more we find cynicism, hypocrisy, and repression. A layperson can avoid a confrontation with the impotence of her beliefs by imagining that if only she were more involved, things would be better. But those who are most involved often have no fantasy left to sustain them. They've been to the center and discovered the center is no better than the edges. But now they rely on the center for support, so they give themselves to support it.

Now, it should be noted that Rollins large project is to posit that religious conviction cannot fill the void in our hearts, in fact nothing can fill the void in our hearts and that it's the very attempt to fill such a void that Jesus can to free us from, so this should be read in that light - it's not that a particular belief or way of life is impotent, simply that these are impotent to make us feel completely satisfied.

Just in light of all the mess that's been (and continues) going on at the center of our denomination, this really struck home. While we might not be fundamentalists, our conception of sanctification certainly holds that place pragmatically in our structure and belief. We theologically nuance things, but at the core is this notion that once we're sanctified we shouldn't be going back to old ways of doing things - sanctified people can be trusted implicitly, our leaders are people of integrity at all times, etc.

I won't argue against holiness; I believe it strongly, but there is a sense of unbelief buried deep that allows us to live with it in our everyday lives. We're learning to express it more and more, but it's going to be tough to do so honestly at the very core of our structure.

I think it's certainly healthy for us to be able to say "yes, we believe in sanctification, but the way it ends up being worked out in real life is more than a little messy." Lots of us are more comfortable doing so these days, but we don't have a structure that can support such statements and perhaps it's taking a real toll on the people we put in the middle of that structure.

I won't say any of our leaders are going through this kind of existential crisis, but in reading the Rollins quote above, it sure brought to mind the events of the last couple years (and maybe longer).

Thursday, December 10, 2015

Beyond One Dimension

This is the second post inspired by a quote my Dad shared on Facebook the other day:*

(I wrote in the first post more about how these types of statements function within societies and individuals. This post will be less deep and more a working out of my own sociological categorization of political positions.)

This statement is certainly true and descriptive of a certain type of person. We may know people who resemble this depiction, more likely we know people who come really close. Everything is a continuum, right? There are very few instances when people embody an extreme (and when that happens we tend to make them the extreme, even if it's conceivable someone could go beyond - a la Hitler).

That being said, I do think this underlying point can be a good left end of the political spectrum. At it's core, the extreme left comes from a place where the people in power (or those who aspire to power, be it dictators or voters) assume "people are basically good and we just need to provide them with a society that allows them to make good choices." At the other end of such a spectrum, the extreme right can be roughly defined by those in power (or aspiring to power) assuming "people are basically evil and must be constrained in order to behave rightly."

"Wait,!" you say, "I don't like either of those positions."

Right you are, by their very definition extremes are repugnant. This particular articulation of extremes, though, essentially assumes protectionist control over people, either because people need protection from outside forces or because people need protection from each other. This is why talking about a one dimensional continuum is problematic.

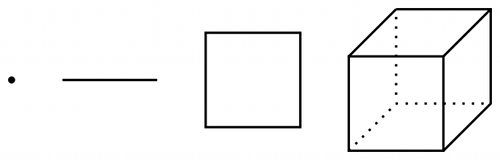

For American politics we might add a second axis to the grid. For clarity sake we'll call it Top and Bottom (you'll see why later). The extreme top assumes everyone is basically capable of taking care of themselves and just needs to be left alone. While the extreme bottom believes people are inherently incapable of individual existence and need the larger community to ensure basic needs.

To define the corners of a grid like this is a study in absurdity, but you can generally look at it as more control to the left and right and more freedom to the top and bottom, with varying definitions of how freedom and control work themselves out in relationship to other people.

Like any good, unbiased chart maker, I see myself precisely in the middle. Ultimately, the extremes betray the same fears. Left and right are terrified of being unsafe and fall into the trap of either trying to create a world where no one would think of hurting anyone or a world in which no one is actually capable of hurting anyone. Top and bottom are each afraid of not having enough and fall into the trap of either creating a world where no one will hold us back or one where no one will let us fail.

In every scenario, the system becomes the bad guy, even if that system is to have no system (as the extreme top position holds). To me, the solution is simply to say every system is functional and dysfunctional. People are basically good and basically evil - if left to live in a vacuum, they will continue to do both awesome and tragic things. We're also all inherently capable of a lot and really, really incapable of a whole lot, too; left to live in a vacuum, we'd be both terribly responsible and terribly irresponsible.

I guess this post should've come first, because it's from here you delve into the kinds of things I said on Tuesday. But what I think is more telling is that we can't really stop with two axes either. I mean, there will be an up and down axis and a south-southwest by north-northwest axis and any other conceivable axis until we've got a sphere - which, in my corniest heart of hearts I want to stand for the world on which we all live.

It would be a great illustration for the idea that beyond any system or ideology we might profess, we have to live together, and very likely there's no "right" way to live - or if there is, there's very little chance we'll figure that out. We can only be present with the people and in the places we are present and try to do "right" by them. The one thing I think we really can't afford to do, is create categories of "other." I'm not saying we have to all be the same (that's pretty much the opposite of what I'm saying), what we have to realize, to embody is that no one is entirely different and no one is entirely alike. We have to push back against these inborn desires to categorize and define people as anything other than individuals. We're all beyond one dimension (or two, or three), so we need to stop treating each other that way.

*This should in no way imply I am accusing my father or anything other than having good taste in quotes. I've seen a lot of people use the quote to make various inferences about policy and beliefs that I'm not sure are implicit in the quoted statement above. We all sort of have to deal with our reactions to it honestly.

(I wrote in the first post more about how these types of statements function within societies and individuals. This post will be less deep and more a working out of my own sociological categorization of political positions.)

Guns, for or against, is not the issue. Sin is the issue. Jesus is the answer for all of us. He is the Prince of Peace!

"Put simply, today’s liberalism cannot deal with the reality of evil. So liberals inveigh against the instruments the evil use rather than the evil that motivates them." – WILLIAM MCGURN, The Liberal Theology of Gun Control, Guns are what you talk about to avoid having to talk about Islamist terrorism., The Wall Street Journal, December 7, 2015

This statement is certainly true and descriptive of a certain type of person. We may know people who resemble this depiction, more likely we know people who come really close. Everything is a continuum, right? There are very few instances when people embody an extreme (and when that happens we tend to make them the extreme, even if it's conceivable someone could go beyond - a la Hitler).

That being said, I do think this underlying point can be a good left end of the political spectrum. At it's core, the extreme left comes from a place where the people in power (or those who aspire to power, be it dictators or voters) assume "people are basically good and we just need to provide them with a society that allows them to make good choices." At the other end of such a spectrum, the extreme right can be roughly defined by those in power (or aspiring to power) assuming "people are basically evil and must be constrained in order to behave rightly."

"Wait,!" you say, "I don't like either of those positions."

Right you are, by their very definition extremes are repugnant. This particular articulation of extremes, though, essentially assumes protectionist control over people, either because people need protection from outside forces or because people need protection from each other. This is why talking about a one dimensional continuum is problematic.

For American politics we might add a second axis to the grid. For clarity sake we'll call it Top and Bottom (you'll see why later). The extreme top assumes everyone is basically capable of taking care of themselves and just needs to be left alone. While the extreme bottom believes people are inherently incapable of individual existence and need the larger community to ensure basic needs.

To define the corners of a grid like this is a study in absurdity, but you can generally look at it as more control to the left and right and more freedom to the top and bottom, with varying definitions of how freedom and control work themselves out in relationship to other people.

Like any good, unbiased chart maker, I see myself precisely in the middle. Ultimately, the extremes betray the same fears. Left and right are terrified of being unsafe and fall into the trap of either trying to create a world where no one would think of hurting anyone or a world in which no one is actually capable of hurting anyone. Top and bottom are each afraid of not having enough and fall into the trap of either creating a world where no one will hold us back or one where no one will let us fail.

In every scenario, the system becomes the bad guy, even if that system is to have no system (as the extreme top position holds). To me, the solution is simply to say every system is functional and dysfunctional. People are basically good and basically evil - if left to live in a vacuum, they will continue to do both awesome and tragic things. We're also all inherently capable of a lot and really, really incapable of a whole lot, too; left to live in a vacuum, we'd be both terribly responsible and terribly irresponsible.

I guess this post should've come first, because it's from here you delve into the kinds of things I said on Tuesday. But what I think is more telling is that we can't really stop with two axes either. I mean, there will be an up and down axis and a south-southwest by north-northwest axis and any other conceivable axis until we've got a sphere - which, in my corniest heart of hearts I want to stand for the world on which we all live.

It would be a great illustration for the idea that beyond any system or ideology we might profess, we have to live together, and very likely there's no "right" way to live - or if there is, there's very little chance we'll figure that out. We can only be present with the people and in the places we are present and try to do "right" by them. The one thing I think we really can't afford to do, is create categories of "other." I'm not saying we have to all be the same (that's pretty much the opposite of what I'm saying), what we have to realize, to embody is that no one is entirely different and no one is entirely alike. We have to push back against these inborn desires to categorize and define people as anything other than individuals. We're all beyond one dimension (or two, or three), so we need to stop treating each other that way.

*This should in no way imply I am accusing my father or anything other than having good taste in quotes. I've seen a lot of people use the quote to make various inferences about policy and beliefs that I'm not sure are implicit in the quoted statement above. We all sort of have to deal with our reactions to it honestly.

Tuesday, December 08, 2015

Convenient Excuses

This is the first of two posts inspired by something my father shared on Facebook the other day:*

As a counter (and for the purposes of this argument), we could also say, "Simply put, today's conservatism cannot deal with the reality of evil. So conservatives inveigh against specific types of people rather than the evil that lies within each of us."

These are equally accurate and equally inaccurate. Accurate insomuch that they describe real positions real people hold, but, of course, inaccurate because they fail to describe the real motivations of everyone a speaker might term conservative or liberal. In short, they're convenient excuses - half-truths we tell ourselves to prevent us from challenging our own comfortable feelings.

I can hear Peter Rollins in the back of my head right now, maybe because I've been reading and hearing too much of him lately or maybe because he's right, but he'd be saying, "of course none of us is comfortable with these strongly held beliefs, but we cling to them strongly in order to avoid the real uncertainty of unbelief."

What he's saying is that many gun control advocates really do respect and covet the notion of personal security, recognize the importance of personal freedom, but don't see an easy compromise, so they cling to an intracted position as a means of avoiding the messy compromise of reality. In the same way, gun control opponents really do recognize the damage guns do in society and struggle with the tension between freedom and safety, but holding to a definitive position is simply easier for the brain to handle, at least on the surface and in the short term.

We use convenient excuses to avoid uncertainty.

Rollins always uses the example of religious belief. Some people believe deeply in faith healing, but will take their grandmother to the hospital when she's having a heart attack, because, despite their genuine and sincerely held belief, there's enough unbelief to act more rationally when the situation calls for it. He argues that the real danger in these groups is not from those who overtly challenge core beliefs, but those who really do believe them without question. It's not the person who laughs at faith healing who's the enemy; the doubter merely helps to bring the faithful closer together. The real enemy is the person who will let grandma die while they pray over here, when there's an ER right down the street. Those people possess no unbelief at all, and they're dangerous.

This also proves the benefit and the danger of convenient excuses. The line above is certainly true of some people - those are the true believers, right? But it put the "other" in a Catch-22. If someone defending gun control as a core belief is faced with this accusation, they likely agree, but can't rightly say, "you're right, this describes some people in our movement," because then they're recognizing the very irrational, true believers, who pose a threat to their position, the ones who might expose it for the horror it is.

Similarly, someone from the gun rights movement can't rightly say "true, this scapegoating is wrong and an easy way out," without betraying the loyalty they have to the underlying message, without exposing the true believers as a problem to the position.

We're seeing this in our political process right now. We've got Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, each of whom may or may not be true believers, but two men who are certainly convincing others of the fidelity of their ideologies. They representing the true believers that those in the establishment can't rightly denounce and can't rightly support. Most people in both parties recognize the ideological comfort Sanders and Trump provide, but also recognize the untenable reality of either actually becoming President.

The convenient excuses are, at the same time, being embodied like never before, yet are also being unmasked in uniquely real and uncomfortable ways.

I think about how this plays out in my own faith tradition. Despite our best theological efforts to do otherwise, the Church of the Nazarene still largely paints an expectation of perfection in its teaching and preaching. We're at least expected to be getting better as people over the years. This manifests itself in genuine difficulty dealing with regression. An alcoholic is welcome to be a part of the church, even as they are still dealing with their disease, but once they have conquered it (however that's described) and gained sort of full membership in the eyes and inner-workings of the community, any relapse or recurrence creates existential problems. Our learned theology doesn't have a way with dealing well with such relapse. Once a sin is defeated, it's supposed to stay dead.

Now that bears out in reality with the allowance of some sins to remain. If things are unspoken, or the individual in question doesn't take too prominent a role, things can be overlooked. Lots of Nazarene congregations have ashtrays by the back door and lots of people smoke, despite its denunciation. Part of the reason is that we have grace, which is real and genuine, part of the reason is because it's easy to allow some "smaller" problems as a trade off for dealing with big ones.

Now, of course this isn't universal - there are lots of communities who find awesome and graceful ways of handling even the most difficult challenges, but it would be tough to argue they are the majority. At the very least, that argument is a convenient excuse - partly true in fact, but indicative of a larger problem.

I'm sure it stems from our primitive brain functions that want to reduce everything to black and white, right and wrong. We want categorization. This is a good person, that is a bad person. This is a moral act, that is an immoral act. Convenient excuses allow us to do that, because they're clothed in real, actual, undeniable truth. We fight over them because admitting any real truth in someone else's convenient excuse forces us to throw away the convenient excuses we're using to avoid our own messy situations.

Rollins talks about unmasking these convenient excuses (although I'm not sure he uses that term) and how doing so creates high levels of anxiety. Our natural reaction is do push down the anxiety, usually by denying the problem, fighting to defend a convenient excuse (either as right or wrong). He suggests and I'd like to find (help create) a community of people who feel safe enough with each other to get beyond the convenient excuses, who form a supportive enough community that we can faithfully live in the mess of uncertainty and healthily deal with the anxiety it produces rather than running from it.

*This should in no way imply I am accusing my father or anything other than having good taste in quotes. I've seen a lot of people use the quote to make various inferences about policy and beliefs that I'm not sure are implicit in the quoted statement above. We all sort of have to deal with our reactions to it honestly.

Guns, for or against, is not the issue. Sin is the issue. Jesus is the answer for all of us. He is the Prince of Peace!

"Put simply, today’s liberalism cannot deal with the reality of evil. So liberals inveigh against the instruments the evil use rather than the evil that motivates them." – WILLIAM MCGURN, The Liberal Theology of Gun Control, Guns are what you talk about to avoid having to talk about Islamist terrorism., The Wall Street Journal, December 7, 2015

As a counter (and for the purposes of this argument), we could also say, "Simply put, today's conservatism cannot deal with the reality of evil. So conservatives inveigh against specific types of people rather than the evil that lies within each of us."

These are equally accurate and equally inaccurate. Accurate insomuch that they describe real positions real people hold, but, of course, inaccurate because they fail to describe the real motivations of everyone a speaker might term conservative or liberal. In short, they're convenient excuses - half-truths we tell ourselves to prevent us from challenging our own comfortable feelings.

I can hear Peter Rollins in the back of my head right now, maybe because I've been reading and hearing too much of him lately or maybe because he's right, but he'd be saying, "of course none of us is comfortable with these strongly held beliefs, but we cling to them strongly in order to avoid the real uncertainty of unbelief."

What he's saying is that many gun control advocates really do respect and covet the notion of personal security, recognize the importance of personal freedom, but don't see an easy compromise, so they cling to an intracted position as a means of avoiding the messy compromise of reality. In the same way, gun control opponents really do recognize the damage guns do in society and struggle with the tension between freedom and safety, but holding to a definitive position is simply easier for the brain to handle, at least on the surface and in the short term.

We use convenient excuses to avoid uncertainty.

Rollins always uses the example of religious belief. Some people believe deeply in faith healing, but will take their grandmother to the hospital when she's having a heart attack, because, despite their genuine and sincerely held belief, there's enough unbelief to act more rationally when the situation calls for it. He argues that the real danger in these groups is not from those who overtly challenge core beliefs, but those who really do believe them without question. It's not the person who laughs at faith healing who's the enemy; the doubter merely helps to bring the faithful closer together. The real enemy is the person who will let grandma die while they pray over here, when there's an ER right down the street. Those people possess no unbelief at all, and they're dangerous.

This also proves the benefit and the danger of convenient excuses. The line above is certainly true of some people - those are the true believers, right? But it put the "other" in a Catch-22. If someone defending gun control as a core belief is faced with this accusation, they likely agree, but can't rightly say, "you're right, this describes some people in our movement," because then they're recognizing the very irrational, true believers, who pose a threat to their position, the ones who might expose it for the horror it is.

Similarly, someone from the gun rights movement can't rightly say "true, this scapegoating is wrong and an easy way out," without betraying the loyalty they have to the underlying message, without exposing the true believers as a problem to the position.

We're seeing this in our political process right now. We've got Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, each of whom may or may not be true believers, but two men who are certainly convincing others of the fidelity of their ideologies. They representing the true believers that those in the establishment can't rightly denounce and can't rightly support. Most people in both parties recognize the ideological comfort Sanders and Trump provide, but also recognize the untenable reality of either actually becoming President.

The convenient excuses are, at the same time, being embodied like never before, yet are also being unmasked in uniquely real and uncomfortable ways.

I think about how this plays out in my own faith tradition. Despite our best theological efforts to do otherwise, the Church of the Nazarene still largely paints an expectation of perfection in its teaching and preaching. We're at least expected to be getting better as people over the years. This manifests itself in genuine difficulty dealing with regression. An alcoholic is welcome to be a part of the church, even as they are still dealing with their disease, but once they have conquered it (however that's described) and gained sort of full membership in the eyes and inner-workings of the community, any relapse or recurrence creates existential problems. Our learned theology doesn't have a way with dealing well with such relapse. Once a sin is defeated, it's supposed to stay dead.

Now that bears out in reality with the allowance of some sins to remain. If things are unspoken, or the individual in question doesn't take too prominent a role, things can be overlooked. Lots of Nazarene congregations have ashtrays by the back door and lots of people smoke, despite its denunciation. Part of the reason is that we have grace, which is real and genuine, part of the reason is because it's easy to allow some "smaller" problems as a trade off for dealing with big ones.

Now, of course this isn't universal - there are lots of communities who find awesome and graceful ways of handling even the most difficult challenges, but it would be tough to argue they are the majority. At the very least, that argument is a convenient excuse - partly true in fact, but indicative of a larger problem.

I'm sure it stems from our primitive brain functions that want to reduce everything to black and white, right and wrong. We want categorization. This is a good person, that is a bad person. This is a moral act, that is an immoral act. Convenient excuses allow us to do that, because they're clothed in real, actual, undeniable truth. We fight over them because admitting any real truth in someone else's convenient excuse forces us to throw away the convenient excuses we're using to avoid our own messy situations.

Rollins talks about unmasking these convenient excuses (although I'm not sure he uses that term) and how doing so creates high levels of anxiety. Our natural reaction is do push down the anxiety, usually by denying the problem, fighting to defend a convenient excuse (either as right or wrong). He suggests and I'd like to find (help create) a community of people who feel safe enough with each other to get beyond the convenient excuses, who form a supportive enough community that we can faithfully live in the mess of uncertainty and healthily deal with the anxiety it produces rather than running from it.

*This should in no way imply I am accusing my father or anything other than having good taste in quotes. I've seen a lot of people use the quote to make various inferences about policy and beliefs that I'm not sure are implicit in the quoted statement above. We all sort of have to deal with our reactions to it honestly.

Thursday, December 03, 2015

Worship, Life, and Corporate Worship

I read this post by Scot McKnight way back in August and am just now getting around to writing about it. Sorry.

He's got some good things to say there, specifically about how corporate worship has become institutionalized in a specific format that's difficult to change. He begins to suggest some ways to be more diverse and inclusive in how we interact corporately, but I'm not sure he really goes far enough.

I'd start with an understanding of worship. Worship is really everything we do - from the time we spend watching TV to the after school discussions with our kids, to, yes, serving Thanksgiving dinner at the local homeless shelter (oh, yeah, and all that church stuff, too). Worship is our life, because the way we spend our time, the principles by which we actually live, are our expressions of worship.

I don't mean this as a guilt trip - that you should be doing more "worthwhile" stuff with your life, because frankly I don't know and the last thing I'd want to do is badger people into being busier. We don't usually need that help. I am saying that our actions determine our beliefs, not our minds or our mouths. Those actions are worship. It's not something we set aside specific time to do. Worship is life.

That's not to be confused with the specific times people set aside to worship together. Those are intentional (usually, the church stuff) and important. For Christians, specifically in the West, but I imagine almost anywhere, those times look remarkably similar, both to everyone else and to the last 500 years (or more) of Christian tradition.

We gather together, sing some songs, pray some prayers, hear scripture and a homily of some kind. We usually collect money. Very often eating is involved. McKnight suggests some ways to include other elements in that basic structure, but the post referenced above sort of leaves it at that - as if this form of corporate worship is simply a given.

For all the fights that have been fought over the years on style (what kind of songs, prayers, and sermons to hear; how we dress or where we sit), the actual structure of our corporate worship is largely unchanged and near universal. I'm not wondering if, more than changing elements of an existing system, we shouldn't be exploring alternative ways to structure the corporate worship events themselves?

The late, great Phyllis Tickle wrote the seminal, The Great Emergence, around the notion of 500 year (give or take) epochal changes in the structure and function of Christianity. We're certainly in the midst of one of those right now, but it's still very unclear exactly what kinds of reforms and changes will emerge.

There's a lot to be said there (and I likely have and will continue to do so), but I wonder if worship and our perspective on worship won't be one of them? My family and I moved to Middletown, Delaware with a sort of crazy dream. We wanted to move into a community to just be good neighbors. We want to live our worship out in the midst of a people, try to love and serve those around us, and see what happens. It was all sort of based on a different notion of worship - that the acts we're doing to live out our beliefs (that all people are important, that we HAVE to live together and sacrifice to get along, that community is important, etc) are worship and become corporate worship when we do them together.

So far it's been less than explicit. The dream was to have one or two other families make the same move, so there'd be a specifically Christian core of people with the same idea of worship and mission. It would allow us to do corporate worship differently, but intentionally - sharing meals together, helping with child-rearing, sharing our stuff and abilities. To do life together.

It didn't work out exactly that way (there's a lot of "great idea, but not for me," which is cool - but, seriously, it's a great town if you still want to come), but we have found great neighbors in this place. It doesn't look anything like my lofty visions, but it looks like what it's supposed to. We do dinners and parties in our shared back yard, we try to organize community events, we share cars and lawnmowers, we take care of each other's pets and homes and kids.

I see all of this, in some sense, as corporate worship. It's not as fully developed as I'd like, but it's starting from the right place, I think - an understanding of life as worship. There's no need to worry about right beliefs or who has to believe what - it's a relationship of action, caring for one another, learning to develop trust. We trust that our neighbors will come through for us and that we can expose our flaws and weaknesses to them; they won't take advantage of us.

I get the sense in which others will say this isn't specifically Christian, because it's not - at the same time, though, it is. This is the care for others that God challenges us to. It's also fair to say, "this doesn't look much different than any other neighbor relationship out there." Yes and no. I don't think people know or trust their neighbors too often in our world; what's more I'm not sure people even really want to all that much. Yes, it certainly happens some places and we see these kinds of relationships thrive - maybe that's corporate worship, too - even if nobody knows or says that's what's happening.

Now, I'm working on how to do this a little more overtly. I want to have a gathering where we can get together and talk about beliefs - not to argue over which ones are right, but to seek out why our friends and neighbors believe what they believe, to figure out how my beliefs impact my actions, to see things from different perspectives and for each of us to grow deeper in our own journeys towards doing life well.

I think that'll be a lot more specifically religious (if not Christian), but I hope it's not Christian in the way that turns so many people off. As McKnight says in the post above, the way we've done things - what's come to be the standard definition of corporate worship for everyone, whether they participate or not - doesn't work well for everybody; it has a kind of bad reputation, mostly as something unhelpful (at least to those people who don't go, and even some who do). I'd like whatever gathering we manage to put together to be Christian in the sense it looks like Christ - people who are genuinely interested in each other, seek to be life-giving and encouraging, to love and trust one other as we do life together.

I'd love for everyone to be doing this in whatever communities you find yourself a part of, but if you want to come do it here, let's talk.

He's got some good things to say there, specifically about how corporate worship has become institutionalized in a specific format that's difficult to change. He begins to suggest some ways to be more diverse and inclusive in how we interact corporately, but I'm not sure he really goes far enough.

I'd start with an understanding of worship. Worship is really everything we do - from the time we spend watching TV to the after school discussions with our kids, to, yes, serving Thanksgiving dinner at the local homeless shelter (oh, yeah, and all that church stuff, too). Worship is our life, because the way we spend our time, the principles by which we actually live, are our expressions of worship.

I don't mean this as a guilt trip - that you should be doing more "worthwhile" stuff with your life, because frankly I don't know and the last thing I'd want to do is badger people into being busier. We don't usually need that help. I am saying that our actions determine our beliefs, not our minds or our mouths. Those actions are worship. It's not something we set aside specific time to do. Worship is life.

That's not to be confused with the specific times people set aside to worship together. Those are intentional (usually, the church stuff) and important. For Christians, specifically in the West, but I imagine almost anywhere, those times look remarkably similar, both to everyone else and to the last 500 years (or more) of Christian tradition.

We gather together, sing some songs, pray some prayers, hear scripture and a homily of some kind. We usually collect money. Very often eating is involved. McKnight suggests some ways to include other elements in that basic structure, but the post referenced above sort of leaves it at that - as if this form of corporate worship is simply a given.

For all the fights that have been fought over the years on style (what kind of songs, prayers, and sermons to hear; how we dress or where we sit), the actual structure of our corporate worship is largely unchanged and near universal. I'm not wondering if, more than changing elements of an existing system, we shouldn't be exploring alternative ways to structure the corporate worship events themselves?

The late, great Phyllis Tickle wrote the seminal, The Great Emergence, around the notion of 500 year (give or take) epochal changes in the structure and function of Christianity. We're certainly in the midst of one of those right now, but it's still very unclear exactly what kinds of reforms and changes will emerge.

There's a lot to be said there (and I likely have and will continue to do so), but I wonder if worship and our perspective on worship won't be one of them? My family and I moved to Middletown, Delaware with a sort of crazy dream. We wanted to move into a community to just be good neighbors. We want to live our worship out in the midst of a people, try to love and serve those around us, and see what happens. It was all sort of based on a different notion of worship - that the acts we're doing to live out our beliefs (that all people are important, that we HAVE to live together and sacrifice to get along, that community is important, etc) are worship and become corporate worship when we do them together.

So far it's been less than explicit. The dream was to have one or two other families make the same move, so there'd be a specifically Christian core of people with the same idea of worship and mission. It would allow us to do corporate worship differently, but intentionally - sharing meals together, helping with child-rearing, sharing our stuff and abilities. To do life together.

It didn't work out exactly that way (there's a lot of "great idea, but not for me," which is cool - but, seriously, it's a great town if you still want to come), but we have found great neighbors in this place. It doesn't look anything like my lofty visions, but it looks like what it's supposed to. We do dinners and parties in our shared back yard, we try to organize community events, we share cars and lawnmowers, we take care of each other's pets and homes and kids.

I see all of this, in some sense, as corporate worship. It's not as fully developed as I'd like, but it's starting from the right place, I think - an understanding of life as worship. There's no need to worry about right beliefs or who has to believe what - it's a relationship of action, caring for one another, learning to develop trust. We trust that our neighbors will come through for us and that we can expose our flaws and weaknesses to them; they won't take advantage of us.

I get the sense in which others will say this isn't specifically Christian, because it's not - at the same time, though, it is. This is the care for others that God challenges us to. It's also fair to say, "this doesn't look much different than any other neighbor relationship out there." Yes and no. I don't think people know or trust their neighbors too often in our world; what's more I'm not sure people even really want to all that much. Yes, it certainly happens some places and we see these kinds of relationships thrive - maybe that's corporate worship, too - even if nobody knows or says that's what's happening.

Now, I'm working on how to do this a little more overtly. I want to have a gathering where we can get together and talk about beliefs - not to argue over which ones are right, but to seek out why our friends and neighbors believe what they believe, to figure out how my beliefs impact my actions, to see things from different perspectives and for each of us to grow deeper in our own journeys towards doing life well.

I think that'll be a lot more specifically religious (if not Christian), but I hope it's not Christian in the way that turns so many people off. As McKnight says in the post above, the way we've done things - what's come to be the standard definition of corporate worship for everyone, whether they participate or not - doesn't work well for everybody; it has a kind of bad reputation, mostly as something unhelpful (at least to those people who don't go, and even some who do). I'd like whatever gathering we manage to put together to be Christian in the sense it looks like Christ - people who are genuinely interested in each other, seek to be life-giving and encouraging, to love and trust one other as we do life together.

I'd love for everyone to be doing this in whatever communities you find yourself a part of, but if you want to come do it here, let's talk.

Tuesday, December 01, 2015

Our Enemies are Stupid

Yes, this post is late. It's my birthday; I decided not to get up at 5:30.

I'm pretty sure I've talked about this before, but it struck me again this week, so here it is. TIME Magazine had an essay from an American writer living in France, talking about how her 9 year old son understood the Paris attacks. Ultimately, he was too young to really get what was happening and why, but she overhead him telling his friends, "they blew things up because they're stupid." Now that is a fine response from a nine year old. There's not a whole lot more this kid could to do process what's going on. At its core, violence like this is unfathomable. Adults aren't really equipped to process it either. At the same time, we are capable of understanding the people behind such events, if we make an effort to do so. I applaud this kid for making sense of things as best he could, but adults need to do better than, "they did this because they're stupid" (or evil).

We can't just take events or ideas we don't understand and make the people who espouse them "other." We call them stupid or evil. We differentiate them from ourselves, which helps us handle the trauma of an event, but it also makes "those people" easier to dismiss or kill. This very natural response increases the chasm between "them" and "us," rather than moving towards bridging it. We have to get beyond that first reaction - as humans, it's our unique gift to understand and override our instincts; it's what makes us human. Let's all try to be human as we deal with such horror.

Yes, there is a power dynamic behind terrorism, especially with a proclaimed group like Al Qaeda or ISIS. They want power and they're leveraging religion to do it. This is pretty much how religion has been used from it's inception, to manipulate and motivate people in power games.* Islam is not any more inherently violent than any other religion (they've all been used to kill - even Buddhism, which is pretty much built around not killing people) - the sins of explicitly Christian violence are deep and lengthy - but the terrorism we see in the news right now is carried out by some practitioners of an extreme interpretation of Islam. It's true that countries, mainly Saudi Arabia, where this interpretation is supported and revered are not as quick to address this violence as we'd like.

I don't believe this reticence is because they condone the violence (and we can't negate the reality that there's no reason to fight a war if the US will step in and do it for you), rather because they do, in fact, condone the interpretation that underlies it. Even extreme Wahhabism doesn't require violence, at least in the scale and scope we're seeing it from ISIS. It's a difficult proposition to oppose violence without opposing the rationale behind it. It's a tough spot.

I don't think Saudi Arabia wishes the western world didn't exist, but they'd certainly be happier if our culture was less materialistic, sexualized, and attractive. It's reductionistic and unfair to say Saudis don't want their women driving cars because they're afraid of Kim Kardashian, but I do think that statement begins to communicate the fear that fuels the religion that sometimes breaks out in violence.

The violence is wrong. The religion is difficult to understand, but the fear makes sense to me. I'm a parent. I get why freedom is scary. I'm terrified of my daughter making her own choices in the world because I don't want her to get hurt. I'd also be more comfortable with her making the exact choices I'd make, because that would solve a lot of tension in my life. This notion that the world and all its advantages will somehow make her life more painful or less content is terrifying.

We might see Miley Cyrus gyrating around the television and think, "how could her parents allow this to happen," or "what went on in her life that lead to this." But if we had the power to keep that from happening (not the causes necessarily, but the output, the effects) would we do it? And maybe not specifically that thing, but others - people who leave their dogs outside on cold nights or feed their children 68oz Dr. Peppers, what about people who picket abortion clinics or make it more difficult to own a gun? What sorts of freedoms would we curtail if we could. It's a moot question for us, sure, but it's not for the Saudi royal family. They can do just about anything they want. It's a really difficult power to have.

We know people who are ruthless with their children - maybe ruthless with love and grace, but allowing very little freedom and choice. It's certainly easy for me to shake my head at the parents of some of my college classmates, who found even a restrictive Christian college so liberating they made some really terrible choices. But then I look at my own kids and I have a lot of sympathy.

The first thing I thought when I picked up my newborn daughter was, "I'm responsible for this person," it was overwhelming, but it paled in comparison to the overwhelming feeling that came next. The second thing I thought when I picked up my newborn daughter was, "I have to give this person away." Our job as parents, from the very first moment, is to not hold on too tight. Our kids are human beings, individuals, and while we long to shape and form them over time, we have to work, VERY HARD to - gradually, mind you - give them away. We're responsible for making sure they can be self-sufficient, think critically, make sound decisions - but we don't get to determine what those terms mean. They don't belong to us.

This might seem way off course from a post about terrorism, but this is what I think of immediately when terrorists strike. They're trying to play on our fears, because those fears are so real for them. We think "they" don't understand freedom, but I believe they understand it very well, certainly as well as we do, if not more. They get what freedom means and it's scary.

I live in a western world and from my comments above, you can see where I come down on the freedom issue. I think letting go in love is the best way we can run a society (even if our western societies could improve the way we do it). But I've not so refused to examine that choice that I don't understand the other side of it. I get why some societies, countries, religions, people opt for control. It makes sense - it has to make some sense to any parent that's held a child in their arms. It's a tension parents live with every moment of every day.

Yes, this may not have that much to do with terrorism on the surface, but, I believe, deep down this is the divide between the West and the Islamic world. It's about fear. Our society gives the impression we're not afraid of anything - at least in the way we allow such reckless freedom - so terrorist try to instill that fear in hopes we'll change our ways. Perhaps they need to see more of the ways in which we do fear the freedom we allow; it would certainly provide a window into our world that could humanize us enough to prevent violence.

I just hope we can similarly see into the control they live out. It appears heartless and unloving (and maybe for those in positions of power, it is), but at the core I think there is genuine care and love there. No one takes such extreme action out of unfeeling. It's a choice. A different choice than I want to make, but a choice I do kind of understand. It's that understanding that makes truly different people human - and, hopefully, helps us understand enough not to answer violence with violence.

The problem with this back and forth between fear and freedom is that they're not operating on a level playing field. Fear breeds more fear; it's possible to share your fear with others and make them afraid; this is the point of terrorism. It's not really possible to make people free. We can't use force (violent or otherwise) to stop fear, to bring freedom. This is the folly of our "nation building" around the world. It doesn't work that way.

Only love drives out fear. The only effective response to fear is love. And we cannot love that which we consider wholly other. We can't treat people humanely who we've dehumanized. No one is truly stupid; that's just a cop out. People are simply misunderstood. We can disagree without dehumanizing and we can get beyond our fear reactions to love people to freedom. I really believe that. It's the only reason I think this life is worth living.

But we have to get beyond the separation. We have to know each other, or at least make the effort. We can't rely on making someone else evil or stupid to let us off the hook. We may have opponents or adversaries, but we don't have enemies. Life doesn't work that way.

*Now, this isn't the only use of religion, so my statement shouldn't been seen as a condemnation of religion. I do have real concerns about the place of religion in our lives and society and, if you're an avid reader here, am pretty sympathetic to the notion of "religionless Christianity" as expressed by Bonhoeffer and explored currently by people like Peter Rollins - but I don't think the argument that "religion hurts people," so often espoused by prominent atheists makes sense, at least not for the reasons they so often use.

I'm pretty sure I've talked about this before, but it struck me again this week, so here it is. TIME Magazine had an essay from an American writer living in France, talking about how her 9 year old son understood the Paris attacks. Ultimately, he was too young to really get what was happening and why, but she overhead him telling his friends, "they blew things up because they're stupid." Now that is a fine response from a nine year old. There's not a whole lot more this kid could to do process what's going on. At its core, violence like this is unfathomable. Adults aren't really equipped to process it either. At the same time, we are capable of understanding the people behind such events, if we make an effort to do so. I applaud this kid for making sense of things as best he could, but adults need to do better than, "they did this because they're stupid" (or evil).

We can't just take events or ideas we don't understand and make the people who espouse them "other." We call them stupid or evil. We differentiate them from ourselves, which helps us handle the trauma of an event, but it also makes "those people" easier to dismiss or kill. This very natural response increases the chasm between "them" and "us," rather than moving towards bridging it. We have to get beyond that first reaction - as humans, it's our unique gift to understand and override our instincts; it's what makes us human. Let's all try to be human as we deal with such horror.

Yes, there is a power dynamic behind terrorism, especially with a proclaimed group like Al Qaeda or ISIS. They want power and they're leveraging religion to do it. This is pretty much how religion has been used from it's inception, to manipulate and motivate people in power games.* Islam is not any more inherently violent than any other religion (they've all been used to kill - even Buddhism, which is pretty much built around not killing people) - the sins of explicitly Christian violence are deep and lengthy - but the terrorism we see in the news right now is carried out by some practitioners of an extreme interpretation of Islam. It's true that countries, mainly Saudi Arabia, where this interpretation is supported and revered are not as quick to address this violence as we'd like.

I don't believe this reticence is because they condone the violence (and we can't negate the reality that there's no reason to fight a war if the US will step in and do it for you), rather because they do, in fact, condone the interpretation that underlies it. Even extreme Wahhabism doesn't require violence, at least in the scale and scope we're seeing it from ISIS. It's a difficult proposition to oppose violence without opposing the rationale behind it. It's a tough spot.

I don't think Saudi Arabia wishes the western world didn't exist, but they'd certainly be happier if our culture was less materialistic, sexualized, and attractive. It's reductionistic and unfair to say Saudis don't want their women driving cars because they're afraid of Kim Kardashian, but I do think that statement begins to communicate the fear that fuels the religion that sometimes breaks out in violence.

The violence is wrong. The religion is difficult to understand, but the fear makes sense to me. I'm a parent. I get why freedom is scary. I'm terrified of my daughter making her own choices in the world because I don't want her to get hurt. I'd also be more comfortable with her making the exact choices I'd make, because that would solve a lot of tension in my life. This notion that the world and all its advantages will somehow make her life more painful or less content is terrifying.

We might see Miley Cyrus gyrating around the television and think, "how could her parents allow this to happen," or "what went on in her life that lead to this." But if we had the power to keep that from happening (not the causes necessarily, but the output, the effects) would we do it? And maybe not specifically that thing, but others - people who leave their dogs outside on cold nights or feed their children 68oz Dr. Peppers, what about people who picket abortion clinics or make it more difficult to own a gun? What sorts of freedoms would we curtail if we could. It's a moot question for us, sure, but it's not for the Saudi royal family. They can do just about anything they want. It's a really difficult power to have.

We know people who are ruthless with their children - maybe ruthless with love and grace, but allowing very little freedom and choice. It's certainly easy for me to shake my head at the parents of some of my college classmates, who found even a restrictive Christian college so liberating they made some really terrible choices. But then I look at my own kids and I have a lot of sympathy.

The first thing I thought when I picked up my newborn daughter was, "I'm responsible for this person," it was overwhelming, but it paled in comparison to the overwhelming feeling that came next. The second thing I thought when I picked up my newborn daughter was, "I have to give this person away." Our job as parents, from the very first moment, is to not hold on too tight. Our kids are human beings, individuals, and while we long to shape and form them over time, we have to work, VERY HARD to - gradually, mind you - give them away. We're responsible for making sure they can be self-sufficient, think critically, make sound decisions - but we don't get to determine what those terms mean. They don't belong to us.

This might seem way off course from a post about terrorism, but this is what I think of immediately when terrorists strike. They're trying to play on our fears, because those fears are so real for them. We think "they" don't understand freedom, but I believe they understand it very well, certainly as well as we do, if not more. They get what freedom means and it's scary.

I live in a western world and from my comments above, you can see where I come down on the freedom issue. I think letting go in love is the best way we can run a society (even if our western societies could improve the way we do it). But I've not so refused to examine that choice that I don't understand the other side of it. I get why some societies, countries, religions, people opt for control. It makes sense - it has to make some sense to any parent that's held a child in their arms. It's a tension parents live with every moment of every day.