I'll be honest, when I got more than halfway through this book and we were still doing, essentially, preliminary work - setting the stage for a discussion of atonement and salvation - I was a little worried. Yes, because Eric and I had similar theological training (we were even in a class or two together in seminary), much of the important groundwork for his presentation is are things I take for granted. It's not that any of it was unnecessary, in fact I think it makes this book incredibly accessible, it's just that I like to read books for new information, and I was in near total agreement for the first 80 pages. Well, I'm in near-total agreement for the entire book, but you get the idea.

What I needed to do was get out of my own head and read Atonement and Salvation with a little more distance. In truth, it is one the most clear and concise treatments of, really, the whole of Christian theology, I have ever read. While the prose may not be the most elegant you've ever seen, it's clear and insightful - you can tell Vail took great, great care in crafting this book.

What shocked me out of my self-oriented perspective was Chapter 8, where he gets to the real meat of the Atonement and Salvation discussion. Chapter 8 is perhaps the most powerful, important, and accessible chapter of theology I have ever read in any book. It's simply tremendous, maybe not for my personal growth, but as a resource for introducing the average Christian to what has always been a difficult and confusing topic. He builds on all that important preliminary material and crafts a picture of atonement that rings true to experience and reflects the massive, unfathomable love of God, while also taking seriously the whole witness of scripture in really responsible ways.

The final two chapters deal with smaller associated topics, including Christ as peacemaker and a critique of penal substitution theory that both pulls no punches, but also exhibits incredible grace. I began the book wondering who it could possibly be for - it doesn't largely break new ground academically and I couldn't imagine any lay person would want to or be able to work through 141 pages on atonement, but Eric Vail has done it. He presents the theology in an academic and compelling way, but with the deft and simplicity that would allow intent readers of any theological depth to follow the narrative and understand his presentation.

Atonement and Salvation is a real gift to the Church and I'm glad the Nazarene Publishing House continues to cultivate and publish such important material.

Thursday, December 22, 2016

Thursday, December 08, 2016

Build Your Hopes on Things Eternal

I spent some time this morning trying to see if I could adapt Hauerwas and Willimon's Resident Aliens for an adult Sunday School class. Scott Daniels is a man of great wisdom who told me he'd tried in once and the book was just too dense for such a setting. I tried to do it anyway, but his advice allowed me to give up the ghost one chapter in. It's a great chapter, though, and I don't want to waste the effort.

The idea of Resident Aliens is primarily that the Church is a "colony of heaven," in the way that conquerors (they might call themselves explorers or liberators) develop colonies in new lands, which are reflective of the home culture, so the Church is called to be a colony of a different world in the midst of this world. A Greek colony in Egypt would've maintained the Greek attitudes towards education, commerce, and social relations, despite those things being at odds with the larger world they find themselves living in.

Christians are called to live differently - not to make the world in which they live more Christian, but to present an alternative means of living - one reflective of God's intentions for the world as revealed in Christ. Christ then becomes the key to all this. The book says that when Christians look a the world, we see something that cannot be seen without Christ - the story of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection provides a lens by which we see the whole concept of life differently.

I was reminded of a song we sung in worship a few weeks back. It's entitled "Hold to God's Unchanging Hand," and contains a line that really caught my attention: "Build your hopes on things eternal," which I imagine has traditionally been looked upon as escapist. There's a long modern Christian tradition of viewing the world as imperfect and temporary, thus the common advice when things go poorly is "don't worry, there's another world out there somewhere; think about eternity."

I see this line more in terms of what Hauerwas and Willimon are trying to say: that there is an entirely different way of looking at this world, an eternal view, a "heavenly" view, something more reflective of what God has in mind, as revealed in Christ.

This difference shows up in the second challenge of Resident Aliens' first chapter: to ask the right theological questions. The authors argue that we typically engage the politics of the world on their own terms - this stretches all the way back to Constantine, the Roman Emperor who first embraced Christianity as a unifying force. Since then we've largely asked "how can we run this world in Christian ways?" It's become a political preoccupation that's gotten us nothing but trouble. Instead, what Willimon and Hauerwas propose is that we ask "What would the world look like if it reflected the gospel?"

This is what I think of when I hear, "Build your hopes on things eternal." We don't have to take the systems and structures we have as inevitable. God calls us to build our lives on a different set of principles and realities, to be a true alternative to the way things seem to work in the world around us. This is the colony concept; the Church's purpose is to be something different, not take the world around us and make it different.

I know the immediate "but" in this is "but if you succeed in building an alternative, won't that just attract 'the world' to join, thereby changing the world into something Christian?" In a sense, yes, of course that leads into conversations about HOW precisely that is done - through an actual attempt to change or through a faithful representation of an alternative - but even that is getting ahead of ourselves, right? We're assuming that living faithfully into an alternative is easy - that establishing and maintain this colony of heaven is a given. It's hard work.

The book goes on to talk specifically about how our politics (in whatever way we've worked them out) have failed us and challenging the Church to a new kind of politics, one that operate on its own system, rather than trying to co-opt the systems around us. There's plenty to delve into there, and I'd love to have those conversations if you want to dialogue about them, but I think this first notion is a really important start.

Build your life on things eternal is not about spiritualizing everything, but it's also not about digging in to physical-ize everything either. We've had quite enough of activist Christianity already. I think rather the call is to have our foundational understandings shaped and formed by the gospel rather than by the world in which we live. We have to stop taking for granted the "realities" we're presented with and imagine our realities in light of God's revelation in Christ.

Well, just some random thoughts on a Thursday. Cheerio.

The idea of Resident Aliens is primarily that the Church is a "colony of heaven," in the way that conquerors (they might call themselves explorers or liberators) develop colonies in new lands, which are reflective of the home culture, so the Church is called to be a colony of a different world in the midst of this world. A Greek colony in Egypt would've maintained the Greek attitudes towards education, commerce, and social relations, despite those things being at odds with the larger world they find themselves living in.

Christians are called to live differently - not to make the world in which they live more Christian, but to present an alternative means of living - one reflective of God's intentions for the world as revealed in Christ. Christ then becomes the key to all this. The book says that when Christians look a the world, we see something that cannot be seen without Christ - the story of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection provides a lens by which we see the whole concept of life differently.

I was reminded of a song we sung in worship a few weeks back. It's entitled "Hold to God's Unchanging Hand," and contains a line that really caught my attention: "Build your hopes on things eternal," which I imagine has traditionally been looked upon as escapist. There's a long modern Christian tradition of viewing the world as imperfect and temporary, thus the common advice when things go poorly is "don't worry, there's another world out there somewhere; think about eternity."

I see this line more in terms of what Hauerwas and Willimon are trying to say: that there is an entirely different way of looking at this world, an eternal view, a "heavenly" view, something more reflective of what God has in mind, as revealed in Christ.

This difference shows up in the second challenge of Resident Aliens' first chapter: to ask the right theological questions. The authors argue that we typically engage the politics of the world on their own terms - this stretches all the way back to Constantine, the Roman Emperor who first embraced Christianity as a unifying force. Since then we've largely asked "how can we run this world in Christian ways?" It's become a political preoccupation that's gotten us nothing but trouble. Instead, what Willimon and Hauerwas propose is that we ask "What would the world look like if it reflected the gospel?"

This is what I think of when I hear, "Build your hopes on things eternal." We don't have to take the systems and structures we have as inevitable. God calls us to build our lives on a different set of principles and realities, to be a true alternative to the way things seem to work in the world around us. This is the colony concept; the Church's purpose is to be something different, not take the world around us and make it different.

I know the immediate "but" in this is "but if you succeed in building an alternative, won't that just attract 'the world' to join, thereby changing the world into something Christian?" In a sense, yes, of course that leads into conversations about HOW precisely that is done - through an actual attempt to change or through a faithful representation of an alternative - but even that is getting ahead of ourselves, right? We're assuming that living faithfully into an alternative is easy - that establishing and maintain this colony of heaven is a given. It's hard work.

The book goes on to talk specifically about how our politics (in whatever way we've worked them out) have failed us and challenging the Church to a new kind of politics, one that operate on its own system, rather than trying to co-opt the systems around us. There's plenty to delve into there, and I'd love to have those conversations if you want to dialogue about them, but I think this first notion is a really important start.

Build your life on things eternal is not about spiritualizing everything, but it's also not about digging in to physical-ize everything either. We've had quite enough of activist Christianity already. I think rather the call is to have our foundational understandings shaped and formed by the gospel rather than by the world in which we live. We have to stop taking for granted the "realities" we're presented with and imagine our realities in light of God's revelation in Christ.

Well, just some random thoughts on a Thursday. Cheerio.

Labels:

church,

colony,

ecclesiology,

eternal,

hauerwas,

Heaven,

hymns,

life,

poliics,

purpose,

resident aliens,

scott daniels,

willimon

Tuesday, December 06, 2016

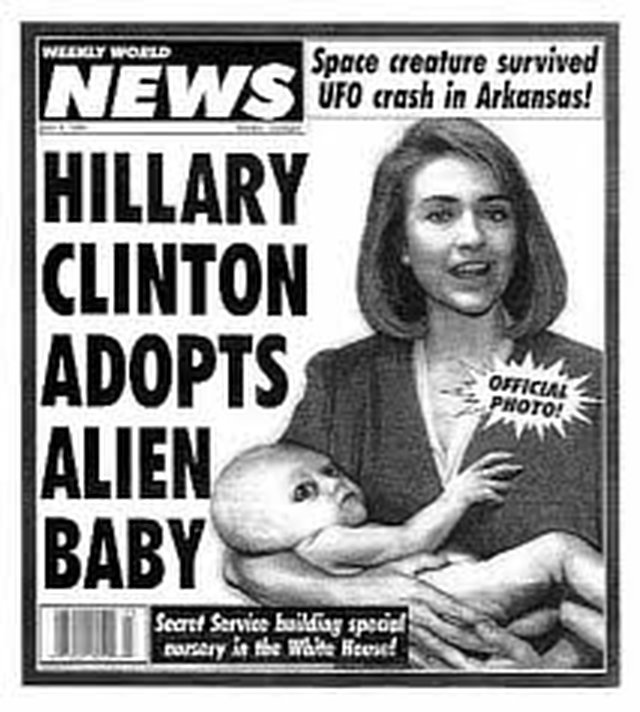

I Love Fake News

Maybe this has cycled out of the public consciousness in the weeks since the election, but I saw another story about it today, so why not wade in, right? I like fake news. I don't think it's a problem for anyone, except maybe actual journalists and their employers. The problem is us. People read "news" looking to have their own ideas reinforced and bolstered, seeking support for their "team" in this political game we call life. No one bother to double check a source or do their own research - we just decide if something makes sense and go with it.

If you really look at this "fake news" stuff, yeah there's some talk that it's being secretly funded by foreign governments to mess with US elections, but for the most part, it's a product of economic disparity in a globalized world. Most of this stuff comes from shops set up in rural Macedonia, where low-level gangsters pay school children to write (or even just copy and paste) stories about the US elections in their off hours. With the advent of online advertising, you don't need any actual substance, just a headline click-baity enough to draw interest. People get paid for the eyeballs on the ads - that's all that matters. Fake news is no different than kitten videos or clever memes - it's just content meant to make someone money.

It might be poor satire, but it's certainly inventive - well, some of it - the best fake news is genuinely creative and clever, people make up stories that other people want to read. We live in a world where almost everyone universally doubts the bias of the press, even historic, well-established journalistic brands - even if a fake news site bills itself as real news, people are conditioned not to trust media. Heck, even fake news sites like the Onion that are overtly up-front about the fakeness of their news still end up getting retweeted by actual elected officials.

The problem is not some masquerading pseudo-journalist who's really a fourth grader in Gostivar (look it up); the problem is us. The great Western Individualism that we've come to know and love (and claim is the reason much of those who hate us hate us) has led us to be self-absorbed egotists, assuming that our common sense is the closet approximation to truth. We're also lazy. It doesn't take much in this internet age to research a story and then utilize that profound common sense with, you know, a basic level of information. It's the same internet these fake news sites mine to figure out what stories we might click on and then provide them to us.

If you listen to any of the numerous reporting pieces on fake news, you can hear interviews with these kids and their bosses. They're not interested in shaping US policy (although they take pride in the fact that they are), they just want to make money. If people click on Trump stories, they'll write Trump stories. It's industrious and inventive and intelligent - all things you need to be to avoid falling for this kind of news.

I hear all this hand-wringing from people lamenting the place fake news held in the recent election and I've heard nothing about the responsibility of a society to educate its people and motivate them to perform basic functions. It's not like you have to drive down to some college library to look up economic charts from the past five years - you type a couple words into google and you click on a few "about us" tabs and then you click on google a few more times to verify the information you're finding.

Yeah, it's not perfect, but the more information one has the better capable we are of making real, informed choices. Not doing the work to be informed is our fault, not someone else's.

I love fake news. If I'd had time and a little more internet marketing savvy, it sounds like a fun way to make some money. I like writing. I'm pretty creative. I'm pretty knowledgeable about the political landscape. I bet I'd be really good at it. About ten years ago, when I had a break from grad school, I'd go onto Yahoo Answers and write long, details answers to questions that were entirely false. For example, one girl was trying to get help with her homework on Romeo and Juliet and I described in 1500 words, the plot of A Streetcar Named Desire (I just used the names Romeo and Juliet instead of Stanley and Stella).

There's really no excuse for believing something just because it sounds good. I imagine it has to do with our aversion to suffering - we only work as much as we have to work, and we try to avoid it as much as possible. Talk to a middle school teacher sometime - one of the most difficult things to teach is research - good research - it's too easy to get into a mindset of "it says this somewhere" and "their opinions is as valid as anyone else's." I don't disagree with the opinion part, but there's a certain level of knowledge that's assumed. Opinions are equally valid when they come from the same level of knowledge. My opinions on the origin of black holes is not nearly as valid as that of Neil DeGrasse Tyson. If I were ever going to disagree with him, I'd have to do a lot of actual work to gain the kind of knowledge I'd need to do so.

That or I could just tweet some fake news at him.

Sadly, in the court of public opinion, that would probably be enough to win the argument. But that's not my fault; it's the fault of all those people who believe me. Don't penalize creative people exercising their gifts for a better economic future. Let's pull the plank out of our own eye before we go after the speck in someone else's. I feel like that's good advice I heard somewhere once.

If you really look at this "fake news" stuff, yeah there's some talk that it's being secretly funded by foreign governments to mess with US elections, but for the most part, it's a product of economic disparity in a globalized world. Most of this stuff comes from shops set up in rural Macedonia, where low-level gangsters pay school children to write (or even just copy and paste) stories about the US elections in their off hours. With the advent of online advertising, you don't need any actual substance, just a headline click-baity enough to draw interest. People get paid for the eyeballs on the ads - that's all that matters. Fake news is no different than kitten videos or clever memes - it's just content meant to make someone money.

It might be poor satire, but it's certainly inventive - well, some of it - the best fake news is genuinely creative and clever, people make up stories that other people want to read. We live in a world where almost everyone universally doubts the bias of the press, even historic, well-established journalistic brands - even if a fake news site bills itself as real news, people are conditioned not to trust media. Heck, even fake news sites like the Onion that are overtly up-front about the fakeness of their news still end up getting retweeted by actual elected officials.

The problem is not some masquerading pseudo-journalist who's really a fourth grader in Gostivar (look it up); the problem is us. The great Western Individualism that we've come to know and love (and claim is the reason much of those who hate us hate us) has led us to be self-absorbed egotists, assuming that our common sense is the closet approximation to truth. We're also lazy. It doesn't take much in this internet age to research a story and then utilize that profound common sense with, you know, a basic level of information. It's the same internet these fake news sites mine to figure out what stories we might click on and then provide them to us.

If you listen to any of the numerous reporting pieces on fake news, you can hear interviews with these kids and their bosses. They're not interested in shaping US policy (although they take pride in the fact that they are), they just want to make money. If people click on Trump stories, they'll write Trump stories. It's industrious and inventive and intelligent - all things you need to be to avoid falling for this kind of news.

I hear all this hand-wringing from people lamenting the place fake news held in the recent election and I've heard nothing about the responsibility of a society to educate its people and motivate them to perform basic functions. It's not like you have to drive down to some college library to look up economic charts from the past five years - you type a couple words into google and you click on a few "about us" tabs and then you click on google a few more times to verify the information you're finding.

Yeah, it's not perfect, but the more information one has the better capable we are of making real, informed choices. Not doing the work to be informed is our fault, not someone else's.

I love fake news. If I'd had time and a little more internet marketing savvy, it sounds like a fun way to make some money. I like writing. I'm pretty creative. I'm pretty knowledgeable about the political landscape. I bet I'd be really good at it. About ten years ago, when I had a break from grad school, I'd go onto Yahoo Answers and write long, details answers to questions that were entirely false. For example, one girl was trying to get help with her homework on Romeo and Juliet and I described in 1500 words, the plot of A Streetcar Named Desire (I just used the names Romeo and Juliet instead of Stanley and Stella).

There's really no excuse for believing something just because it sounds good. I imagine it has to do with our aversion to suffering - we only work as much as we have to work, and we try to avoid it as much as possible. Talk to a middle school teacher sometime - one of the most difficult things to teach is research - good research - it's too easy to get into a mindset of "it says this somewhere" and "their opinions is as valid as anyone else's." I don't disagree with the opinion part, but there's a certain level of knowledge that's assumed. Opinions are equally valid when they come from the same level of knowledge. My opinions on the origin of black holes is not nearly as valid as that of Neil DeGrasse Tyson. If I were ever going to disagree with him, I'd have to do a lot of actual work to gain the kind of knowledge I'd need to do so.

That or I could just tweet some fake news at him.

Sadly, in the court of public opinion, that would probably be enough to win the argument. But that's not my fault; it's the fault of all those people who believe me. Don't penalize creative people exercising their gifts for a better economic future. Let's pull the plank out of our own eye before we go after the speck in someone else's. I feel like that's good advice I heard somewhere once.

Thursday, December 01, 2016

The Cross and the Idol

One of the revolutionary things about this YHWH who rescued God's people from slavery, led them through the wilderness, and secured for them a land and a future was that YHWH was always present. Even before what we Christian term "the incarnation," God was incarnated among the Hebrews. God was with them. It's why, when we read the famously accommodated prophesy about Immanuel, we don't have to claim it's foretelling a specific future about a baby in a manger, but that it's describing a constant reality: God is with us. God is present.

Part of the problem in Israel was that they took a God who could not be contained and made a box, called a temple. Pretty quickly, as you might imagine, the God who infused and inhabited all things was confined to the religious. Instead of life being worship in all of its minutia, worship became something people did in a specific place, at a specific time, in a specific way. Oh there was always rituals, but they were rituals pointing and imaging the everyday actions of the people. And no, there's no reason why religion can't still be practiced in that way (and is!), but you have to admit it's a lot easier to keep religion in a corner when the God at the center of it is wrapped up in a neat little box.

This is why it was so necessary for God to be re-incarnated - to show up in a living, breathing person - to explode back into the world that God's people had pushed God out of. No longer would God be segregated to the temple, but would be active and alive in the world. It's no wonder that Jesus seemed to reject the trappings of the temple and the religious system that had built up around it over the intervening years: there were more important things to do. Life was to be lived - lived in the way it had been created to be enjoyed. In Jesus we see a person fully inhabiting his personhood, humanity being truly human - even to the point of giving up that humanity for the sake of others.

What did we do then? Well, for a while we lived into that example. There were lots of people sacrificing and going to their deaths out of love for neighbor and enemy alike. That tradition continues; let's not say it's faded away. But what it means to be Christian, in general, over time, has faded away. We've taken that great sacrifice of love and imaged it - imbuing meaning and honor on the instrument of Christ's death and giving it pride of place in our sanctuaries.

Again, I am not arguing that the cross is misplaced or ill-used or inappropriate. For certainly the reminder of death is key to our lives as God intended them. What is most important is not blessing or survival, but sacrifice - the meaning of life is to give it away in whatever manner we are called. Love, of course, but how much love? The cross reminds us there is no limit to such love.

But we've still contained it in a box. Yes, we may wear it on a chain around our necks or tattoo it on our calves or adorn it on our clothes, but for all practical purposes we've locked it up tight in our houses of worship just as Samuel did all those many years ago. It's a method of control, for one - when God is in our box, we decide how and when and where people experience and respond to God. There's safety and security in that - the same kinds of things the cross challenges us to forsake.

This domestication is also a means of ignoring the creative purpose of our lives: to live freely and wholly into God's future. When the cross is locked up in the church, we can relegate the Kingdom to that place and time we choose to think of it. We no longer have to infuse our lives with the radical, counter-cultural otherness that so characterized the one who died upon that cross, the one who rescued a people from slavery and lived among them as they wandered, poor and helpless in the desert. We can abandon the call of God to be humble when we've made the symbol of that God to important.

That's the catch, though, isn't it. God first told God's people not to make images of worship. We brush off the Muslim desire to keep their God and prophet unseen, but forget that our tradition has the same command. Yes, we're a bit more of a gracious people, at least in paper, but the teaching is the same: do not make idols - images that depict God - because God has made the only image necessary: us. Christ, as Paul says, the very image of the invisible God, is humanity as it was intended. We are God's image. We do not have the right to make another, simply because it better serves our purpose.

The cross is a call for our lives to embrace God's purpose. We must take it up and lay it down in service of God's radical love, not our own convenient agenda. It is not an excuse to make one place sacred and another secular. It is not permission to lie and steal and cheat in our everyday lives, because something better exists in another world. Something better exists, alright, but it's not in another world, it's in the world God created this one to become.

The means by which God is transforming the world God created into the world God intended is love. The path that transformation takes is through our lives and witness, not through our religious rituals and houses of worship. That shouldn't demean or diminish the importance of those things in our lives, but it does radically alter the way we view the cross. It is not an image to be exalted and looked up, but one to be shouldered and carried.

Carried out of the boxes we have created for it and into the world where it - and we - were meant to really live.

Part of the problem in Israel was that they took a God who could not be contained and made a box, called a temple. Pretty quickly, as you might imagine, the God who infused and inhabited all things was confined to the religious. Instead of life being worship in all of its minutia, worship became something people did in a specific place, at a specific time, in a specific way. Oh there was always rituals, but they were rituals pointing and imaging the everyday actions of the people. And no, there's no reason why religion can't still be practiced in that way (and is!), but you have to admit it's a lot easier to keep religion in a corner when the God at the center of it is wrapped up in a neat little box.

This is why it was so necessary for God to be re-incarnated - to show up in a living, breathing person - to explode back into the world that God's people had pushed God out of. No longer would God be segregated to the temple, but would be active and alive in the world. It's no wonder that Jesus seemed to reject the trappings of the temple and the religious system that had built up around it over the intervening years: there were more important things to do. Life was to be lived - lived in the way it had been created to be enjoyed. In Jesus we see a person fully inhabiting his personhood, humanity being truly human - even to the point of giving up that humanity for the sake of others.

What did we do then? Well, for a while we lived into that example. There were lots of people sacrificing and going to their deaths out of love for neighbor and enemy alike. That tradition continues; let's not say it's faded away. But what it means to be Christian, in general, over time, has faded away. We've taken that great sacrifice of love and imaged it - imbuing meaning and honor on the instrument of Christ's death and giving it pride of place in our sanctuaries.

Again, I am not arguing that the cross is misplaced or ill-used or inappropriate. For certainly the reminder of death is key to our lives as God intended them. What is most important is not blessing or survival, but sacrifice - the meaning of life is to give it away in whatever manner we are called. Love, of course, but how much love? The cross reminds us there is no limit to such love.

But we've still contained it in a box. Yes, we may wear it on a chain around our necks or tattoo it on our calves or adorn it on our clothes, but for all practical purposes we've locked it up tight in our houses of worship just as Samuel did all those many years ago. It's a method of control, for one - when God is in our box, we decide how and when and where people experience and respond to God. There's safety and security in that - the same kinds of things the cross challenges us to forsake.

This domestication is also a means of ignoring the creative purpose of our lives: to live freely and wholly into God's future. When the cross is locked up in the church, we can relegate the Kingdom to that place and time we choose to think of it. We no longer have to infuse our lives with the radical, counter-cultural otherness that so characterized the one who died upon that cross, the one who rescued a people from slavery and lived among them as they wandered, poor and helpless in the desert. We can abandon the call of God to be humble when we've made the symbol of that God to important.

That's the catch, though, isn't it. God first told God's people not to make images of worship. We brush off the Muslim desire to keep their God and prophet unseen, but forget that our tradition has the same command. Yes, we're a bit more of a gracious people, at least in paper, but the teaching is the same: do not make idols - images that depict God - because God has made the only image necessary: us. Christ, as Paul says, the very image of the invisible God, is humanity as it was intended. We are God's image. We do not have the right to make another, simply because it better serves our purpose.

The cross is a call for our lives to embrace God's purpose. We must take it up and lay it down in service of God's radical love, not our own convenient agenda. It is not an excuse to make one place sacred and another secular. It is not permission to lie and steal and cheat in our everyday lives, because something better exists in another world. Something better exists, alright, but it's not in another world, it's in the world God created this one to become.

The means by which God is transforming the world God created into the world God intended is love. The path that transformation takes is through our lives and witness, not through our religious rituals and houses of worship. That shouldn't demean or diminish the importance of those things in our lives, but it does radically alter the way we view the cross. It is not an image to be exalted and looked up, but one to be shouldered and carried.

Carried out of the boxes we have created for it and into the world where it - and we - were meant to really live.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)