I'm a little behind, but in catching up on potential post ideas, I ran across this link I saved from Easter weekend. I saw it on CNN and was curious what Ed Stetzer, who I've known to be pretty creative, might have to say about "Why do Christians keep inviting you to Church?" I'm sure it was a boon for CNN, who's become quite click-baity these days, to have a recognized evangelical name talking about church on Easter weekend, but I was really disappointed by the lack of, well, anything in this piece.

The main ideas at the top, which CNN always pulls out for those too lazy to read more than three sentences, say "Christians who share their faith aren't intolerant," and "It shows they believe what Jesus said and care about those around them." To me, it all seems a bit tone deaf. The column basically argues (very politely) against the notion that its offensive to try and influence someone else's belief - and I'm sure that's an issue for some people.

His main points, though, that it's not intolerant because Jesus told Christians to do it, that everyone wants to influence people when they find something they're passionate about, and that Christians really believe Jesus changes lives, aren't wrong, but they're likely missing the point.

He points out, rightly, that Penn Jillette, the entertainer and oft-critique of Christianity has said many times he only trusts Christians who try to convert him, because it seems hypocritical to believe someone is going to hell and not do everything you can to stop it.

I'm just not sure that's why people are uncomfortable with invitations to church. I don't disagree, necessarily, with Stetzer's three points here,

but I think one easy misconception is the unaddressed source of the real problem. Evangelical Christianity, especially in the US, particularly of the fundamentalist tradition, is obsessed with apologetics - a word most people have never heard. Apologetics is essentially the verbal and logical argument for faith; young evangelicals are trained from an early age to "be able to give an answer for the hope that you have," which, in typically fundamentalist fashion, is taking one verse and ratcheting up its importance to an almost comic level.

It's made of good intentions most of the time, but it creates all kinds of problems - namely that no one can be talked into faith. Yes, CS Lewis is a prime example of someone who reasoned his way to Christianity, but it wasn't reason alone; there is a real difference between faith and theology (although, in the world of apologetics, that might not be true). The other problem is that Jesus' "call" to do such things was really a call to "make disciples," which has gotten translated into, "lovingly argue people into faith." Many evangelicals think, if they can't do it,

at least get this person to church, where the pastor can take a crack at it.

I'd say, from my perspective, this is the most important misinterpretation of scripture in evangelical culture today, the notion that "make disciples" equals proselytizing. There is far more scriptural support for the Church to live faithfully as a means of witness and allowing God to draw people to Christian faith and practice. This doesn't preclude talking to people about faith and developing relationships with those around us, but it's got a very different purpose at the core - it's me trying to be the best Christian I can be, vs me trying to make you into a follower of Christ.

Maybe I'm wrong about that - you're certainly free to disagree - but I think it fits with why, I suspect, people are often uncomfortable with the invitation to church: we're not living what we claim.

I get that nobody's perfect and people expecting Christians to be wonderful people is a big hurdle for Christian to overcome. As we Christians like to say, "We're all just sinners." However, when we use our words to try and convince people, when we set our worship services up as a means of converting or proselytizing, we're sort of communicating that we've got something you don't. There's an implicit judgement, even if it's not done judgmentally.

If we respect people as people, we need to respect that they've arrived at whatever beliefs they have honestly, through experience and thought.

Stetzer asks that people give Christians a chance, listen to them and don't just write everything off right away. I'd say that's good advice,

but it's good advice for everyone, Christians included. My faith has been shaped and challenged positively far more often by talking to people who don't share it than it ever has listening to a sermon or sitting in a class.

Yes, I do believe most of the time when people ask you to come to church its because they believe Jesus can make every life better. I share that belief. But also, it's often because they don't feel confident enough in themselves to present Jesus honestly. This is what has to change.

We say "We're just sinners," and get upset when people expect Christians to be perfect, but we're rarely willing to be imperfect, to be real,

to be honest with people we're "trying to save."

Even that phrase is really missing the point. Christians often view themselves as standing on the shore throwing life preservers to loved ones who are drowning - but w'd be more effective (not to mention accurate) if we thought of everyone (ourselves included) as struggling in the water.

Just because we're pretty convinced of the best way to shore, doesn't mean we shouldn't listen to what those around us have to say.

I suspect people get uncomfortable with invitations to church for a lot of reasons (unfamiliarity being the biggest), but I don't think an aversion to intolerance is high on the list. I suspect there is some internal notion that "you don't have it all together, why tell me what to do?"

I hope that's an unfair assessment of every Christian and every congregation, but we all know it's not. Perceptions chance not from words - in our mouths or on CNN - perceptions change with action and experience. The change begins with me.

Thursday, April 27, 2017

Tuesday, April 25, 2017

Preach, Pray, or Die

At the close of business for our most recent District Assembly (the annual meeting of our local group of congregations in the Church of the Nazarene) our District Superintendent invited, seemingly unprompted, his father to close the gathering with prayer. His father made the comment that when he joined the Church of the Nazarene someone told him Nazarenes need always be prepared "to pray, preach, or die." It drew great laughs, which proved even more amusing as the scheduled preacher for the service that evening lost his voice and our DS had to fill in on very short notice.

I appreciated the statement, though, because it speaks to an urgency that, to me, is the only hallmark of the evangelical movement. I know much has been made of the cultural, political, even theological benchmarks for such a title, but if we stay true to the word itself - which literally means "the bearing of good news." Granted, even the dictionary adds some rather partisan and particular details to the definition of the word, but I'm still willing to claim history on my side.

It's that urgency - not that the world is coming to an end and we need to covert as many as possible, but that this gospel, this good news, is important and there's an urgency to take it seriously in our decisions and lives - that appeals to me so greatly. I'm not sure there are any "official" evangelical groups who'd want me as a member after theological review, but I'll claim that affinity as long as I live (I hope) strictly for that reason: I seek to bear the Good News with not just my words, but with my actions, commitments, and decisions, with great seriousness.

I believe one of the hallmarks of that seriousness is the willingness to sacrifice, something perhaps many cultural evangelicals (and certainly the movement at large) has forgotten - with the general response to outrage being a demanding of rights rather than a surrender of comfort. I don't hear anyone deny that a life in imitation of Christ demands sacrifice, but see very few actively seeking ways to do so.

Granted, it might just be perspective. I can recount many intentional sacrifices me and my family have made in honest pursuit of embodying the gospel, but I could see strong critiques coming my way about the privilege and comfort with which we live. I don't mean my criticism of evangelicalism to be from a position of judgement, but I do spy a lack of intention. We, as a people (American evangelicals, for sure, but probable Western Christianity at large), are afraid to suffer for our beliefs. We might be prepared to preach or pray (although that could be less and less true as time goes on, probably no coincidence), but we are very reticent to die (even metaphorically).

I've been giving conservatives a bit of a hard time thus far, so it's time to turn the tables a bit. I was thinking of this statement a lot during our District Assembly, while also hearing many reports from the Young Clergy Conference that had taken place the week before. Over 100 Nazarene clergy under the age of forty had gathered in Oklahoma City to listen, learn, and dialogue in support of each other. It seems like a super cool event, one I am very sorry to have missed and hope to attend next year (also one I am very supportive of, please don't get me wrong). It's also a group, as is true of just about any "young" contingent from anywhere, tends to be more progressive (in the true sense of 'moving forward' and not the modern sense of 'a weasel word to replace liberal').

The most common description I heard of the conference was that it was a safe space for young clergy to discuss issues that might be problematic elsewhere. I agree and affirm that this is important - and, having been young once, understand the very real ramifications of such difficult talk on someone early in their career and with a tenuous grip on finances. The wrong reputation, earned or otherwise, can basically end a clergy career, at least in the Church of the Nazarene; it's career path without much of a safety net.

The second most common thing I heard from the event was the importance of a message from Jon Middendorf (the host pastor and someone who used to be the face of Nazarene young clergy, you know, when he was young). It was relayed to me that he challenged these young people not to leave the denomination when things got difficult, but to "stay and fight," but not with ways and means the world might associate with fighting, but fighting in imitation of Christ, with love and sacrifice.

It's a powerful message, but as I heard it and the rest of the event recounted, it struck me that many were not really making the connection between "fighting" and sacrifice. Issues discussed at that conference and the perspective of the younger generation in the Church of the Nazarene are vitally important, although perhaps uncomfortable for the denomination at large, often, despite rhetoric to the contrary, downright unwelcome. Making an evangelical stand might just cost us - maybe more than we're prepared or feel safe sacrificing.

This young generation (which, in this context is still the millenials, although the real "young" generation is probably already the one after that*) has grown up in a very security-conscious environment. It's second nature to triple check our protective measures before venturing any risk at all. This is great for surviving to adulthood without debilitating injury or unsightly scarring, but it makes sacrifice difficult. A generation told the world was their oyster only to grow up and become the first generation in US history to not have things better than their parents is difficult - even moreso when they were raised on safety.

What I'm saying is it's easy to retreat, to only risk and sacrifice manageable chunks of our lives (and this certainly applies to me, too). Today's future leaders need to hear that voice from today's former leaders that says "Always be prepared to pray, preach, or die," and we need to pay extra close attention to that last part and all of its implications for the world in which we live. Die might not mean martyrdom of our physical bodies, but it might just mean martyrdom of the life to which we've become accustomed.

*I should also say, in full disclosure, that I am NOT among this group. Most dating of millenials starts with January of 1982, which I missed by a month, but more importantly, I just don't fit any of the typical definitions culturally or in terms of mindset. I am part of what I tend to dub "the lost generation," a real brief transition time in between cultural groups, where we feel as unlike Generation X as we do millenials -

perhaps the best hallmark of which is the internet. We were fully formed adults before the internet really became a regular part of our lives,

but it happened early enough that we're generally native to the technology - although never in ways that millenials or the following generation tends to be. All that to say - I'm speaking critically of a group of which I, myself, am not a part, so please take what I have to say with appropriate levels of salt.

I appreciated the statement, though, because it speaks to an urgency that, to me, is the only hallmark of the evangelical movement. I know much has been made of the cultural, political, even theological benchmarks for such a title, but if we stay true to the word itself - which literally means "the bearing of good news." Granted, even the dictionary adds some rather partisan and particular details to the definition of the word, but I'm still willing to claim history on my side.

It's that urgency - not that the world is coming to an end and we need to covert as many as possible, but that this gospel, this good news, is important and there's an urgency to take it seriously in our decisions and lives - that appeals to me so greatly. I'm not sure there are any "official" evangelical groups who'd want me as a member after theological review, but I'll claim that affinity as long as I live (I hope) strictly for that reason: I seek to bear the Good News with not just my words, but with my actions, commitments, and decisions, with great seriousness.

I believe one of the hallmarks of that seriousness is the willingness to sacrifice, something perhaps many cultural evangelicals (and certainly the movement at large) has forgotten - with the general response to outrage being a demanding of rights rather than a surrender of comfort. I don't hear anyone deny that a life in imitation of Christ demands sacrifice, but see very few actively seeking ways to do so.

Granted, it might just be perspective. I can recount many intentional sacrifices me and my family have made in honest pursuit of embodying the gospel, but I could see strong critiques coming my way about the privilege and comfort with which we live. I don't mean my criticism of evangelicalism to be from a position of judgement, but I do spy a lack of intention. We, as a people (American evangelicals, for sure, but probable Western Christianity at large), are afraid to suffer for our beliefs. We might be prepared to preach or pray (although that could be less and less true as time goes on, probably no coincidence), but we are very reticent to die (even metaphorically).

I've been giving conservatives a bit of a hard time thus far, so it's time to turn the tables a bit. I was thinking of this statement a lot during our District Assembly, while also hearing many reports from the Young Clergy Conference that had taken place the week before. Over 100 Nazarene clergy under the age of forty had gathered in Oklahoma City to listen, learn, and dialogue in support of each other. It seems like a super cool event, one I am very sorry to have missed and hope to attend next year (also one I am very supportive of, please don't get me wrong). It's also a group, as is true of just about any "young" contingent from anywhere, tends to be more progressive (in the true sense of 'moving forward' and not the modern sense of 'a weasel word to replace liberal').

The most common description I heard of the conference was that it was a safe space for young clergy to discuss issues that might be problematic elsewhere. I agree and affirm that this is important - and, having been young once, understand the very real ramifications of such difficult talk on someone early in their career and with a tenuous grip on finances. The wrong reputation, earned or otherwise, can basically end a clergy career, at least in the Church of the Nazarene; it's career path without much of a safety net.

The second most common thing I heard from the event was the importance of a message from Jon Middendorf (the host pastor and someone who used to be the face of Nazarene young clergy, you know, when he was young). It was relayed to me that he challenged these young people not to leave the denomination when things got difficult, but to "stay and fight," but not with ways and means the world might associate with fighting, but fighting in imitation of Christ, with love and sacrifice.

It's a powerful message, but as I heard it and the rest of the event recounted, it struck me that many were not really making the connection between "fighting" and sacrifice. Issues discussed at that conference and the perspective of the younger generation in the Church of the Nazarene are vitally important, although perhaps uncomfortable for the denomination at large, often, despite rhetoric to the contrary, downright unwelcome. Making an evangelical stand might just cost us - maybe more than we're prepared or feel safe sacrificing.

This young generation (which, in this context is still the millenials, although the real "young" generation is probably already the one after that*) has grown up in a very security-conscious environment. It's second nature to triple check our protective measures before venturing any risk at all. This is great for surviving to adulthood without debilitating injury or unsightly scarring, but it makes sacrifice difficult. A generation told the world was their oyster only to grow up and become the first generation in US history to not have things better than their parents is difficult - even moreso when they were raised on safety.

What I'm saying is it's easy to retreat, to only risk and sacrifice manageable chunks of our lives (and this certainly applies to me, too). Today's future leaders need to hear that voice from today's former leaders that says "Always be prepared to pray, preach, or die," and we need to pay extra close attention to that last part and all of its implications for the world in which we live. Die might not mean martyrdom of our physical bodies, but it might just mean martyrdom of the life to which we've become accustomed.

*I should also say, in full disclosure, that I am NOT among this group. Most dating of millenials starts with January of 1982, which I missed by a month, but more importantly, I just don't fit any of the typical definitions culturally or in terms of mindset. I am part of what I tend to dub "the lost generation," a real brief transition time in between cultural groups, where we feel as unlike Generation X as we do millenials -

perhaps the best hallmark of which is the internet. We were fully formed adults before the internet really became a regular part of our lives,

but it happened early enough that we're generally native to the technology - although never in ways that millenials or the following generation tends to be. All that to say - I'm speaking critically of a group of which I, myself, am not a part, so please take what I have to say with appropriate levels of salt.

Thursday, April 20, 2017

Just Stop, Please

So, this guy, Reggie Osborne, poured his well-intentioned heart out on his personal blog more than a year ago and, for some reason, it's found its way to viral now. I see lots of my Christian friends sharing and praising this post. I'm going to savage it - I think it's deluded, misguided, and dangerous - but I don't want this to be some attack or rebuke on Reggie himself. He's coming from the right place - in fact, I think I agree with what might be his most important sentence, in reference to today's youth, "They’ve heard the message and believed it: 'Sex is no big deal'." That's the point in this thing, he just surrounds it with so much outrageous bunk, I'm enraged.

Yes, I recognize that he wrote a follow up to clarify some of the more egregious inferences, but that doesn't remove them from the piece. The impetus for the article was a California law requiring affirmative consent training in high school sex ed. To quote from the piece,

I get that he's outraged this is something that would have to be taught in school, but there's nothing in the piece supportive or affirmative of this idea at all. I think it comes from a naivte about the past that we evangelicals like to nurture, that there was a time when conservative Christian morality was the societal norm and people "behaved" themselves. This just isn't true.

Sexual assault on college campuses is not a new phenomenon, it's just now become an issue for people in power. Women being taken advantage of is not a new phenomenon; it's just become culturally unacceptable. To think that affirmative consent is the kind of thing we have to do to stem some rising tide of sexual dysfunction is to have your head in the sand. This is the kind of training that's been needed for all of human history. Yes, I, too, am upset that it's needed - and that outrage is justified - but it's not a new need.

He beings the piece with a story about his wedding - how because of the (right and good and agreeable) chastity he and his wife practiced, along with their commitment to life-long marriage, his wife "only said yes once." I understand the meaning; it's about commitment, but that's not how the words read. They're irresponsible in a world (especially a conservative Christian world) where often the man is empowered as dictator in a relationship. The evil of complementarianism is alive and well - and many women are committed to the idea that what their husband says, goes.

I'm not accusing Osborne of this - (well, maybe he's into complementarianism, I don't know - but he makes a strong denouncement of spousal rape in the follow up piece) - but it is real and prevalent still. Sometimes it does apply to sex. I've heard more than one committed Christian address what's appropriate in the bedroom by saying, "once you're married, anything goes," which is fine, if there's real affirmative consent, where one partner actually feels free to say no (I'll try to use partner as often as possible, but sexual pressure in a relationship can come from either partner, and it certainly applies to same-sex relationships, too).

I don't know how it works for other people, but I've pretty much found in my 12 years of marriage that affirmative consent works really well for everything, not just physical intimacy. The majority of Osborne's post seems to be denigrating or marginalizing its importance. As the dad of a daughter, I think it's just about the greatest thing to come along in society in recent years. I am overjoyed knowing that when I empower my daughter to take control of her body there's a whole culture out there supporting that notion. It's not a luxury that women in previous generations enjoyed.

When I read the list of things Osbourne cited he gets to do because his wife said 'yes once,' at their wedding, I just feel sad for her.

I'm sure they've got a great relationship (or as good as any of us) and this was maybe poorly worded, but they're still there, for people to read. None of those things are implied by a wedding. Kissing and sex might be expected (although, again, with real affirmative consent), but I can't imagine too many people (male or female) enjoy being bothered in the shower. It was a real shock early in my marriage when I was told some of the things I did with good intentions to be cute or flirtatious just made my wife uncomfortable and angry (and it took some time of quiet suffering before she told me).

Lack of communication is the easiest way to kill a relationship and, frankly, Christians have done more to make talking about sex and intimacy difficult for couples than anything else. Yes, culture and media have exposed kids to sex more often, earlier, and in unhealthy ways than in past generations. That's absolutely true. Yes, pornography and media portrayals present a distorted view of sex that leads to real relationship problems for people when they have unfair expectations of a partner.

But that doesn't make it the cause of anything. What it's done is force us to talk about things previous generations could've gone their whole lives never bringing up. How many Christian kids heard simply that sex was bad until they're married, then its great, with no other instruction whatsoever? It's a lot. What that leads to is just as much dysfunction, misery, and fear, albeit different from the kinds prevalent today.

The difference now, in this oversexed world, is we have to talk about it or someone else will.

Beyond the way many of these other peripheral issues were poorly addressed, what drives me most nuts about "She Only Said Yes Once," is its blame shifting. Yes, sex has been casualized and devalued and misrepresented in society, but if my child grows up with a messed up perception of sex and its related issues, that's not anyone's fault but mine.

We're afraid of oversexualizing our own kids if we talk about the natural, biological processes of reproduction before they hit puberty. We think we're just going to drive our kids to experimentation and danger if we empower them to make their own decisions about sex after puberty. We want to tell them what to do, but we're afraid they won't listen, so we say nothing at all.

That is when culture and experience and outside voices enter the fray. If you don't want your kids listening to a culture that glorifies selfishness and hedonism through sex, then give them another voice. I won't go into great detail on what I might say, because I've written it a couple times, at least - this one still holds up.

I think the big issue, especially as it relates to Osborne's piece and the way evangelicals have handled sex, is the approach. If you start with "Don't have sex," and follow it with a discussion of the very real and important realities surrounding sex, it just seems like justification for the demand. If you start with, "It's your body and you can use it however you want," the rest becomes honest and caring support as they wrestle with a massive responsibility.

I am positive my daughter will make choices with which I disagree (and not just about sex, either) - when I think about it even now I tear up little - but it's much more important to me that she makes those choices with the broadest reserve of knowledge, the deepest well of thought,

and my unwavering support.

The sexualized world around us is not evidence of its own depravity - we're naive if we think this is anything new - rather it is evidence of our abdication of responsibility to speak life into it.

Yes, I recognize that he wrote a follow up to clarify some of the more egregious inferences, but that doesn't remove them from the piece. The impetus for the article was a California law requiring affirmative consent training in high school sex ed. To quote from the piece,

"Do you want to kiss her? Ask for consent. Do you want to touch her breasts? Ask for consent again. Do you want to take her clothes off? Ask for consent again. Do you want to penetrate? Ask for consent again."

I get that he's outraged this is something that would have to be taught in school, but there's nothing in the piece supportive or affirmative of this idea at all. I think it comes from a naivte about the past that we evangelicals like to nurture, that there was a time when conservative Christian morality was the societal norm and people "behaved" themselves. This just isn't true.

Sexual assault on college campuses is not a new phenomenon, it's just now become an issue for people in power. Women being taken advantage of is not a new phenomenon; it's just become culturally unacceptable. To think that affirmative consent is the kind of thing we have to do to stem some rising tide of sexual dysfunction is to have your head in the sand. This is the kind of training that's been needed for all of human history. Yes, I, too, am upset that it's needed - and that outrage is justified - but it's not a new need.

He beings the piece with a story about his wedding - how because of the (right and good and agreeable) chastity he and his wife practiced, along with their commitment to life-long marriage, his wife "only said yes once." I understand the meaning; it's about commitment, but that's not how the words read. They're irresponsible in a world (especially a conservative Christian world) where often the man is empowered as dictator in a relationship. The evil of complementarianism is alive and well - and many women are committed to the idea that what their husband says, goes.

I'm not accusing Osborne of this - (well, maybe he's into complementarianism, I don't know - but he makes a strong denouncement of spousal rape in the follow up piece) - but it is real and prevalent still. Sometimes it does apply to sex. I've heard more than one committed Christian address what's appropriate in the bedroom by saying, "once you're married, anything goes," which is fine, if there's real affirmative consent, where one partner actually feels free to say no (I'll try to use partner as often as possible, but sexual pressure in a relationship can come from either partner, and it certainly applies to same-sex relationships, too).

I don't know how it works for other people, but I've pretty much found in my 12 years of marriage that affirmative consent works really well for everything, not just physical intimacy. The majority of Osborne's post seems to be denigrating or marginalizing its importance. As the dad of a daughter, I think it's just about the greatest thing to come along in society in recent years. I am overjoyed knowing that when I empower my daughter to take control of her body there's a whole culture out there supporting that notion. It's not a luxury that women in previous generations enjoyed.

When I read the list of things Osbourne cited he gets to do because his wife said 'yes once,' at their wedding, I just feel sad for her.

"Yes, I could kiss her. Yes, I could sleep with her. Yes, I could steal glances of her in the shower because I think she looks great even after 5 kids. She said, “Yes,” to me, forever."

I'm sure they've got a great relationship (or as good as any of us) and this was maybe poorly worded, but they're still there, for people to read. None of those things are implied by a wedding. Kissing and sex might be expected (although, again, with real affirmative consent), but I can't imagine too many people (male or female) enjoy being bothered in the shower. It was a real shock early in my marriage when I was told some of the things I did with good intentions to be cute or flirtatious just made my wife uncomfortable and angry (and it took some time of quiet suffering before she told me).

Lack of communication is the easiest way to kill a relationship and, frankly, Christians have done more to make talking about sex and intimacy difficult for couples than anything else. Yes, culture and media have exposed kids to sex more often, earlier, and in unhealthy ways than in past generations. That's absolutely true. Yes, pornography and media portrayals present a distorted view of sex that leads to real relationship problems for people when they have unfair expectations of a partner.

But that doesn't make it the cause of anything. What it's done is force us to talk about things previous generations could've gone their whole lives never bringing up. How many Christian kids heard simply that sex was bad until they're married, then its great, with no other instruction whatsoever? It's a lot. What that leads to is just as much dysfunction, misery, and fear, albeit different from the kinds prevalent today.

The difference now, in this oversexed world, is we have to talk about it or someone else will.

Beyond the way many of these other peripheral issues were poorly addressed, what drives me most nuts about "She Only Said Yes Once," is its blame shifting. Yes, sex has been casualized and devalued and misrepresented in society, but if my child grows up with a messed up perception of sex and its related issues, that's not anyone's fault but mine.

We're afraid of oversexualizing our own kids if we talk about the natural, biological processes of reproduction before they hit puberty. We think we're just going to drive our kids to experimentation and danger if we empower them to make their own decisions about sex after puberty. We want to tell them what to do, but we're afraid they won't listen, so we say nothing at all.

That is when culture and experience and outside voices enter the fray. If you don't want your kids listening to a culture that glorifies selfishness and hedonism through sex, then give them another voice. I won't go into great detail on what I might say, because I've written it a couple times, at least - this one still holds up.

I think the big issue, especially as it relates to Osborne's piece and the way evangelicals have handled sex, is the approach. If you start with "Don't have sex," and follow it with a discussion of the very real and important realities surrounding sex, it just seems like justification for the demand. If you start with, "It's your body and you can use it however you want," the rest becomes honest and caring support as they wrestle with a massive responsibility.

I am positive my daughter will make choices with which I disagree (and not just about sex, either) - when I think about it even now I tear up little - but it's much more important to me that she makes those choices with the broadest reserve of knowledge, the deepest well of thought,

and my unwavering support.

The sexualized world around us is not evidence of its own depravity - we're naive if we think this is anything new - rather it is evidence of our abdication of responsibility to speak life into it.

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

Nazarenes and Alcohol

It shouldn't be any surprise that I am a member of the clergy in the Church of the Nazarene.

We are a relatively young denomination (110-130 years, depending on who's counting), but one that's always been a bit of a conglomeration.

Initially, we were founded by three diverse groups coming together around the idea of Holiness - which I typically sum up as "living the way God intends for you to live here and now." You might say Nazarene believe you don't need to wait for heaven to be holy. That's more than a bit simplistic, but if you dig down deeper, you'll find out even we don't really know how to explain it out to the end of every argument train.

One of the big issues, historically, for us has been alcohol. The West Coast faction was founded around ministry to the urban poor, where alcohol was a real problem. The Southern wing was pretty moralist and some looked on alcohol as inherently sinful. In any event, they agreed that drinking wasn't good - many participated heavily in the prohibitionist movement. It was a big deal.

As the years have gone on, context and culture changed (although maybe not as much as we tend to think) and our denomination has grown even more diverse, with 70% of the members living outside the US. You will find every, and I mean EVERY, possible position on alcohol both preached and practiced among Nazarenes around the world. It's an issue we've historically been unable to even speak functionally about at our quadrennial General Assemblies.

The next such assembly is set for June of 2017. As part of that, delegates will discuss dozens of amendments from the mundane to the densely theological. As a member, I have the ability to submit proposed changes to my district, where a committee (usually the elected delegates and a few others) determine if it will be submitted to the General Assembly.

I submitted a number of resolutions for consideration, one deals with alcohol. I want to give great credit to my district - the committee invited me to one of their meetings to discuss the resolution and hear my rationale. I am not sure what, if anything, was actually passed on (they have the ability to amend or change anything and the final resolutions haven't been released yet), but I feel like it would be good, with the Assembly coming up, to share my proposal more publicly.

I am not a drinker. Its never been something I've wanted to do. This isn't an issue that really affects me personally. It does, however, effect a lot of people I love and care about. I've known far too many families royally messed up with alcohol a big part of things. Further, I feel a real kinship with those urban founders with a real heart for the poor. It's a perspective that largely kept me a part of the Church of the Nazarene. I don't think we should drink, not because alcohol is inherently bad, but largely because our culture can't handle its collective alcohol. It's good to be a safe, dry place for people.

At the same time, it seems silly to make any sort of fanatical mandate on individual members of the denomination, especially since, in practice,

we have come a long way from a clapboard barn in 1800's Los Angeles. We look different in so many ways. Beyond that, our practice has always been grace - or at least mostly been grace. A few pastors will run people off for having champagne at a wedding, but most won't. We take people into membership who exhibit a lifestyle of holiness, even if it doesn't mesh with every little line in the Manual. We just do. That's reality.

In light of these seemingly contrary realities, I tried to write something that would both make a collective and theological statement and would also allow for individual and contextual freedom. I think both elements are infused with grace, which, I believe, should be at the core of all Christian politics (if you're a new reader, I define politics as "the way we deal with people.") I also strove to keep as much of the current language as possible so as to remind people that this is not a replacement, but an update on a longstanding position we've struggled to fully grasp.

Here is the proposal I submitted:

I'd also point to a great podcast from In All Things Charity that discusses some aspects of the realities of our position on alcohol.

We are a relatively young denomination (110-130 years, depending on who's counting), but one that's always been a bit of a conglomeration.

Initially, we were founded by three diverse groups coming together around the idea of Holiness - which I typically sum up as "living the way God intends for you to live here and now." You might say Nazarene believe you don't need to wait for heaven to be holy. That's more than a bit simplistic, but if you dig down deeper, you'll find out even we don't really know how to explain it out to the end of every argument train.

One of the big issues, historically, for us has been alcohol. The West Coast faction was founded around ministry to the urban poor, where alcohol was a real problem. The Southern wing was pretty moralist and some looked on alcohol as inherently sinful. In any event, they agreed that drinking wasn't good - many participated heavily in the prohibitionist movement. It was a big deal.

As the years have gone on, context and culture changed (although maybe not as much as we tend to think) and our denomination has grown even more diverse, with 70% of the members living outside the US. You will find every, and I mean EVERY, possible position on alcohol both preached and practiced among Nazarenes around the world. It's an issue we've historically been unable to even speak functionally about at our quadrennial General Assemblies.

The next such assembly is set for June of 2017. As part of that, delegates will discuss dozens of amendments from the mundane to the densely theological. As a member, I have the ability to submit proposed changes to my district, where a committee (usually the elected delegates and a few others) determine if it will be submitted to the General Assembly.

I submitted a number of resolutions for consideration, one deals with alcohol. I want to give great credit to my district - the committee invited me to one of their meetings to discuss the resolution and hear my rationale. I am not sure what, if anything, was actually passed on (they have the ability to amend or change anything and the final resolutions haven't been released yet), but I feel like it would be good, with the Assembly coming up, to share my proposal more publicly.

I am not a drinker. Its never been something I've wanted to do. This isn't an issue that really affects me personally. It does, however, effect a lot of people I love and care about. I've known far too many families royally messed up with alcohol a big part of things. Further, I feel a real kinship with those urban founders with a real heart for the poor. It's a perspective that largely kept me a part of the Church of the Nazarene. I don't think we should drink, not because alcohol is inherently bad, but largely because our culture can't handle its collective alcohol. It's good to be a safe, dry place for people.

At the same time, it seems silly to make any sort of fanatical mandate on individual members of the denomination, especially since, in practice,

we have come a long way from a clapboard barn in 1800's Los Angeles. We look different in so many ways. Beyond that, our practice has always been grace - or at least mostly been grace. A few pastors will run people off for having champagne at a wedding, but most won't. We take people into membership who exhibit a lifestyle of holiness, even if it doesn't mesh with every little line in the Manual. We just do. That's reality.

In light of these seemingly contrary realities, I tried to write something that would both make a collective and theological statement and would also allow for individual and contextual freedom. I think both elements are infused with grace, which, I believe, should be at the core of all Christian politics (if you're a new reader, I define politics as "the way we deal with people.") I also strove to keep as much of the current language as possible so as to remind people that this is not a replacement, but an update on a longstanding position we've struggled to fully grasp.

Here is the proposal I submitted:

The Use of Intoxicants

Paragraphs 29.5 and 29.6

Resolved, that paragraph 29.5 be retitled, “The use of intoxicating liquors as a beverage,” and replaced with the following:

Acknowledging that consumption of alcohol, in moderation, is, in itself, not inherently sinful, we recognize the pain and trauma suffered by individuals and families as a result of alcohol abuse and addiction. Society often prefers to hide, ignore, or ostracize these problems.

From its earliest days, the Church of the Nazarene exhibited a special calling to ministry among the poor, lost, and forgotten as primary vocation. Because of this special calling, we ask our members to refrain from alcohol and other intoxicating substances as a symbol of solidarity with those who suffer.

We acknowledge this is not the calling of God for all people or the only way to faithfully respond to addiction, as such, abstinence from alcohol consumption cannot be considered an essential of the Christian faith. We make the choice to abstain from alcohol in response to the biblical mandate of self-giving love for our brothers and sisters. Our position must be embodied with grace and without judgment. In that spirit, we do not hold adherence to this position as required for fellowship, either in the body of Christ or in the Church of the Nazarene.

Further, we should seek to minimize the irresponsible use of alcohol and glorification of the same in society and culture. Effort and attention must be paid to the consequences of irresponsible alcohol use and its effect on people for whom Christ died. The widespread incidence of alcohol abuse in our world demands that we embody a position that stands as a witness to others.

(In light of this stance, only unfermented wine should be used in celebration of the Lord’s Supper.)

Further resolved, that paragraph 29.6 be retitled “The use of other intoxicants, stimulants, or hallucinogens, outside proper medical care and guidance,” and replaced with the following:

In light of medical evidence outlining the dangers of such substances, along with scriptural admonitions to remain in responsible control of mind and body, we choose to abstain from intoxicants, stimulants, and hallucinogens outside proper medical care and guidance, regardless of the legality and availability of such substances.

Reasons:

1. Our statement should reflect a broader directive on the use of intoxicating substances that will guide the practice of our denomination regardless of medical, scientific, and legal changes.

2. Our statement on alcohol should not simply be a condemnation of alcohol, but an understanding of our Christian responsibility to those who suffer from its abuse.

3. In light of the unfortunate judgementalism that has accompanied our interpretation of understanding of alcohol in the past, our statement should reflect grace strongly, in imitation of our savior, Jesus Christ.

I'd also point to a great podcast from In All Things Charity that discusses some aspects of the realities of our position on alcohol.

Thursday, April 13, 2017

The Dawn of Christianity by Robert J Hutchinson

Disclaimer: I was given a free copy of this book for the purpose of review. My integrity is not for sale. Those who know me well are aware a free book isn't enough to assuage my cutting honesty. If I've failed to write a bad review, it has nothing to do with the source of the material and only with the material itself.

Hutchinson proposes this book as a narrative account of Jesus' ministry and the first decades of the Christian movement. He claims to write as a Christian for Christians, but also as an unbiased seeker of truth. This is definitely a conservative perspective, although not militantly so - he gladly posits that Jesus probably didn't cleanse the temple twice, as a harmonized version of the gospels would indicate.

However, there are some basic problems with this approach - 1) it's a bit haphazard. In some areas the logic and argumentation is thorough and spotless (even if I don't always agree); in other areas the argumentation is beyond thin and poorly discussed.* 2) it's a bit cyclical. As a skeptic of the skeptics, Hutchinson is taking a pretty standard perspective on the historicity of the New Testament and puts more value than many on the New Testament witness - this requires a strong foundation of faith, essentially starting with an end point and giving the evidence as much benefit of the doubt as possible. This, in and of itself, is sound, but to then go and build a historical account of the same material using that faith-infused witness as foundation makes the process ever more dicey.

Finally, and this is the biggest issue we have using scripture as historical evidence, is that it leads us to shift the focus from the purpose of scripture - to tell us something about God - and makes it more about history. That might seem self-evident, but, if one is not careful, it ends up in a fundamentalism of both theology and history. I don't think Hutchinson arrives there (or anywhere close), but he uses the road, perhaps without enough caution.

I believe the New Testament is a valid historical witness, but we can never divorce that witness from the theological purpose of the text. If we begin to draw historical conclusions without the lens of genre and purpose we find ourselves in a very untenable position.

That being said, the book is really interesting. It does portend to take a critical-historical look at the timeline of Jesus' last days with an assumption that the gospels are fairly valid historical documents. Part of his plan seems to be to show, from archaeological evidence, that indeed scripture is more accurate to historical reality than often assumed. That case is made. However, there are many times when he uses a traditional perspective and, I'd argue, irresponsible attempts to harmonize the gospels (for example with the anointing of Jesus' feet and the timing of the Last Supper) that detract from this purpose.

It's almost as if there are dual purposes to The Dawn of Christianity - both to provide historical background, but also to affirm traditional understandings of history, sometimes regardless of their appropriateness based on evidence. I was often surprised, though, that Hutchinson presented many parts of the narrative that would shock the typical evangelical; his Jesus is very much human, planning events without the disciple's knowledge and working in very "human" ways to grow a movement strategically.

There are some biblical references Hutchinson obviously deems ahistorical and thus doesn't include (like Jesus re-attaching Malchus' ear at Gethsemane). At the same time, he presents historical and archaeological discovery in the same measure and voice as simple scriptural references, which ultimately makes this book useless to anyone but an expert. It's a great juxtaposition of the biblical narrative with outside information, but with no real division between the two, it lends itself to the grave error of taking scripture as historical narrative rather than just historic theology.

I'd say, if you're really interested in archaeology and history, it's got some great information wrapped in a convenient package, but if you're looking for a serious, critical address of the historicity of the Christian narrative, you'll find very little of value here. It's not that the book is bad; I think its gracious, thorough, and generally well done. I just don't see much practical use for it.

*For example, Hutchsinson compares the historical witness for the New Testament to the historical witness for the Battle of Thermopalae, specifically the 300 Spartans who held off the Persians - and this is an apt and well argued comparison - but he fails to mention that no historian worth their salt actually thinks the story of the 300 is anything but dramatic embellishment; it's not historically received in the same way he believes the New Testament should be. His defense of the possible historicity of John the Baptist's birth prediction is equally erratic.

Disclosure of Material Connection: I received this book free from the publisher through the BookSneeze.com® book review bloggers program. I was not required to write a positive review. The opinions I have expressed are my own. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Hutchinson proposes this book as a narrative account of Jesus' ministry and the first decades of the Christian movement. He claims to write as a Christian for Christians, but also as an unbiased seeker of truth. This is definitely a conservative perspective, although not militantly so - he gladly posits that Jesus probably didn't cleanse the temple twice, as a harmonized version of the gospels would indicate.

However, there are some basic problems with this approach - 1) it's a bit haphazard. In some areas the logic and argumentation is thorough and spotless (even if I don't always agree); in other areas the argumentation is beyond thin and poorly discussed.* 2) it's a bit cyclical. As a skeptic of the skeptics, Hutchinson is taking a pretty standard perspective on the historicity of the New Testament and puts more value than many on the New Testament witness - this requires a strong foundation of faith, essentially starting with an end point and giving the evidence as much benefit of the doubt as possible. This, in and of itself, is sound, but to then go and build a historical account of the same material using that faith-infused witness as foundation makes the process ever more dicey.

Finally, and this is the biggest issue we have using scripture as historical evidence, is that it leads us to shift the focus from the purpose of scripture - to tell us something about God - and makes it more about history. That might seem self-evident, but, if one is not careful, it ends up in a fundamentalism of both theology and history. I don't think Hutchinson arrives there (or anywhere close), but he uses the road, perhaps without enough caution.

I believe the New Testament is a valid historical witness, but we can never divorce that witness from the theological purpose of the text. If we begin to draw historical conclusions without the lens of genre and purpose we find ourselves in a very untenable position.

That being said, the book is really interesting. It does portend to take a critical-historical look at the timeline of Jesus' last days with an assumption that the gospels are fairly valid historical documents. Part of his plan seems to be to show, from archaeological evidence, that indeed scripture is more accurate to historical reality than often assumed. That case is made. However, there are many times when he uses a traditional perspective and, I'd argue, irresponsible attempts to harmonize the gospels (for example with the anointing of Jesus' feet and the timing of the Last Supper) that detract from this purpose.

It's almost as if there are dual purposes to The Dawn of Christianity - both to provide historical background, but also to affirm traditional understandings of history, sometimes regardless of their appropriateness based on evidence. I was often surprised, though, that Hutchinson presented many parts of the narrative that would shock the typical evangelical; his Jesus is very much human, planning events without the disciple's knowledge and working in very "human" ways to grow a movement strategically.

There are some biblical references Hutchinson obviously deems ahistorical and thus doesn't include (like Jesus re-attaching Malchus' ear at Gethsemane). At the same time, he presents historical and archaeological discovery in the same measure and voice as simple scriptural references, which ultimately makes this book useless to anyone but an expert. It's a great juxtaposition of the biblical narrative with outside information, but with no real division between the two, it lends itself to the grave error of taking scripture as historical narrative rather than just historic theology.

I'd say, if you're really interested in archaeology and history, it's got some great information wrapped in a convenient package, but if you're looking for a serious, critical address of the historicity of the Christian narrative, you'll find very little of value here. It's not that the book is bad; I think its gracious, thorough, and generally well done. I just don't see much practical use for it.

*For example, Hutchsinson compares the historical witness for the New Testament to the historical witness for the Battle of Thermopalae, specifically the 300 Spartans who held off the Persians - and this is an apt and well argued comparison - but he fails to mention that no historian worth their salt actually thinks the story of the 300 is anything but dramatic embellishment; it's not historically received in the same way he believes the New Testament should be. His defense of the possible historicity of John the Baptist's birth prediction is equally erratic.

Disclosure of Material Connection: I received this book free from the publisher through the BookSneeze.com® book review bloggers program. I was not required to write a positive review. The opinions I have expressed are my own. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Tuesday, April 11, 2017

Beauty and the Free Market

I'm reading this book, The Confidence Game, about the psychology of belief and the ways in which grifters use our biological proclivities to fool us. It's a very interesting book, that uses lots of real examples to illustrate its points,

however, one in particular struck me for an entirely different reason.

Towards the end of the book, the author, Maria Konnikova, presents the case of Glafira Rosales, a small-time art dealer who conned big-time art dealer Ann Freedman into selling off 63 forged abstract expressionist paintings as real over the course of many years, even buying some herself.

The fakes were so convincing, reknowned art experts, historians, even museums specializing in the period and Mark Rothko's son, Christopher,

were convinced they were real. It was only when so many previously unknown works emerged that people began to be suspicious, but it was never because of the art itself.

The book talked about how we can become blind to our own expertise - of course Freedman believed in the art, she had two in her entryway and saw them everyday. How could she, an expert, be fooled by fakes she saw all the time.

In the end the scheme bankrupted a lot of people and embarrassed far more, but that notion of the dealer looking at fake paintings in her entryway struck me as odd - the economics of the whole thing. If those paintings were truly indistinguishable from de Koonig's style (for none of them were copies of existing art, but art in the style of each artist, passed off as unknown), why would it be any less valuable? Either the thing takes on more beauty because the artist is famous, or the art itself is more valuable because the artist is famous - but neither option really makes sense.

It led me to think about the ways in which we evaluate beauty. The high art world is strange to begin with - none of the immense, grotesque values on famous paintings are truly accurate; as in any free-market system, value is determined solely by how much money one is willing to pay. A modern artist can now sell a written description of an un-made work as art, and bag $10m for the privilege of letting someone imagine what they would've designed. I get the inherent value of such a thing, as well as the philosophical statement its making - and I appreciate both - but I don't understand the monetary value.

Beauty is beauty. Someone may be unwilling to part with a beautiful work of art for $10m, when no one else would pay twenty bucks for it, because its beautiful and you can't put a price on beauty. People on Antiques Road Show like to know how much Grandma's 400 year old rocking chair is worth, but they're never going to sell it - the connection is too priceless. I'm sure there are psychological effects at play here, too, but it's also a statement on beauty. What we find valuable doesn't always equate to money.

Shoot, I write here at least once a week, hopefully twice - the hits aren't terrible. I'm sure I could throw some google adsense boxes up and make a few bucks, but I don't like the idea of not being able to control what products get sold next to my thoughts and words. Whatever small benefit I might receive is outweighed by the very non-monetary cost to my perception of artistry and beauty.

In the end, though, it is kind of sad how the free-market has taken over art. Yes, I'm sure some of the people who spend gobs on paintings and sculpture really appreciate the beauty on the pieces and just happen to have the money to buy them; a lot, however, just like the investment.

The book treated the forged paintings as somehow worthless, simply because the artist was not who people thought it to be. Absent that knowledge, no one - absolutely no one - could tell the difference.

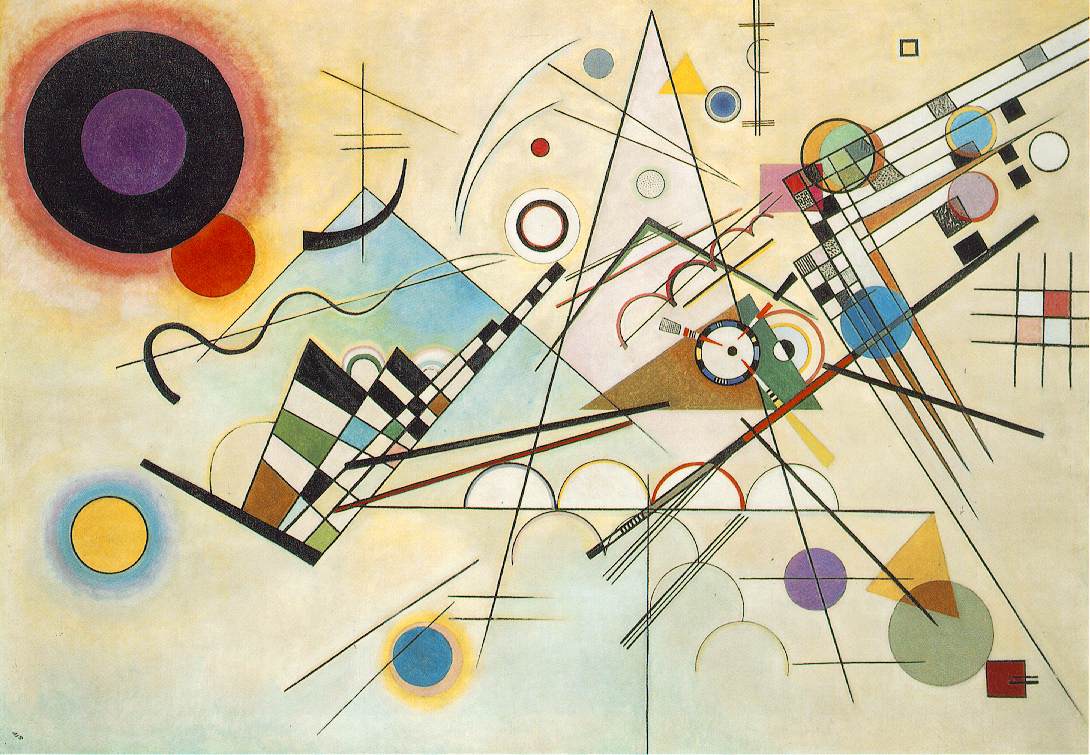

I suppose this could be some grand example of "beauty is truth and truth beauty" right? It is not the artist that makes the painting less valuable, but the deceit? I can see that perspective, but perhaps I'm too naive. I think something beautiful is beautiful. Wasilly Kandinsky is one of my favorite artists. I've seen a lot of his work in person and even more in prints and books. I absolutely love the unusual way his mind and design work - it strikes me as incredibly beautiful. I've also seen a few of his pieces, though, that strike me as downright ugly -

whether its the particular design or the color choices or what have you, I don't like them all simply because he created them.

I get that some Picassos are worth more than others, purportedly because they're better representative of a specific style or a difference in structure or technique - maybe they're even a little less beautiful. But I wonder how they'd be evaluated if the branding of a name weren't attached?

I suppose its impossible to do. Branding is important no matter who you are - JK Rowling continues to use her Robert Galbraith pseudonym for her adult mysteries long after the connection was unmasked. It's branding and removing it probably hinders the artist in some way. At the same time, I wonder how our understanding of beauty and value gets diluted and confounded by the economy of a free market that limits value to simply what money can buy.

however, one in particular struck me for an entirely different reason.

Towards the end of the book, the author, Maria Konnikova, presents the case of Glafira Rosales, a small-time art dealer who conned big-time art dealer Ann Freedman into selling off 63 forged abstract expressionist paintings as real over the course of many years, even buying some herself.

The fakes were so convincing, reknowned art experts, historians, even museums specializing in the period and Mark Rothko's son, Christopher,

were convinced they were real. It was only when so many previously unknown works emerged that people began to be suspicious, but it was never because of the art itself.

The book talked about how we can become blind to our own expertise - of course Freedman believed in the art, she had two in her entryway and saw them everyday. How could she, an expert, be fooled by fakes she saw all the time.

In the end the scheme bankrupted a lot of people and embarrassed far more, but that notion of the dealer looking at fake paintings in her entryway struck me as odd - the economics of the whole thing. If those paintings were truly indistinguishable from de Koonig's style (for none of them were copies of existing art, but art in the style of each artist, passed off as unknown), why would it be any less valuable? Either the thing takes on more beauty because the artist is famous, or the art itself is more valuable because the artist is famous - but neither option really makes sense.

It led me to think about the ways in which we evaluate beauty. The high art world is strange to begin with - none of the immense, grotesque values on famous paintings are truly accurate; as in any free-market system, value is determined solely by how much money one is willing to pay. A modern artist can now sell a written description of an un-made work as art, and bag $10m for the privilege of letting someone imagine what they would've designed. I get the inherent value of such a thing, as well as the philosophical statement its making - and I appreciate both - but I don't understand the monetary value.

Beauty is beauty. Someone may be unwilling to part with a beautiful work of art for $10m, when no one else would pay twenty bucks for it, because its beautiful and you can't put a price on beauty. People on Antiques Road Show like to know how much Grandma's 400 year old rocking chair is worth, but they're never going to sell it - the connection is too priceless. I'm sure there are psychological effects at play here, too, but it's also a statement on beauty. What we find valuable doesn't always equate to money.

Shoot, I write here at least once a week, hopefully twice - the hits aren't terrible. I'm sure I could throw some google adsense boxes up and make a few bucks, but I don't like the idea of not being able to control what products get sold next to my thoughts and words. Whatever small benefit I might receive is outweighed by the very non-monetary cost to my perception of artistry and beauty.

In the end, though, it is kind of sad how the free-market has taken over art. Yes, I'm sure some of the people who spend gobs on paintings and sculpture really appreciate the beauty on the pieces and just happen to have the money to buy them; a lot, however, just like the investment.

The book treated the forged paintings as somehow worthless, simply because the artist was not who people thought it to be. Absent that knowledge, no one - absolutely no one - could tell the difference.

I suppose this could be some grand example of "beauty is truth and truth beauty" right? It is not the artist that makes the painting less valuable, but the deceit? I can see that perspective, but perhaps I'm too naive. I think something beautiful is beautiful. Wasilly Kandinsky is one of my favorite artists. I've seen a lot of his work in person and even more in prints and books. I absolutely love the unusual way his mind and design work - it strikes me as incredibly beautiful. I've also seen a few of his pieces, though, that strike me as downright ugly -

whether its the particular design or the color choices or what have you, I don't like them all simply because he created them.

I get that some Picassos are worth more than others, purportedly because they're better representative of a specific style or a difference in structure or technique - maybe they're even a little less beautiful. But I wonder how they'd be evaluated if the branding of a name weren't attached?

I suppose its impossible to do. Branding is important no matter who you are - JK Rowling continues to use her Robert Galbraith pseudonym for her adult mysteries long after the connection was unmasked. It's branding and removing it probably hinders the artist in some way. At the same time, I wonder how our understanding of beauty and value gets diluted and confounded by the economy of a free market that limits value to simply what money can buy.

Labels:

art,

beauty,

economics,

kandinsky,

maria konnikova,

money,

painting,

the confidence game,

value

Thursday, April 06, 2017

The Danger of Safety

I had opportunity, this weekend, to think once again about why the societal celebration of police sometimes unsettles me. It's not the celebration, I realized, but the way in which we couch those things. I listened to a pastor talk about a first responders Sunday they did - honoring local fire, police, EMS, etc. I was excited about that - no conflict at all. People who serve others so selflessly and importantly deserve as much recognition as we can give.

It was the next sentence that struck me difficult. He said, "We prayed a shield of protection around the people who shield and protect us." In that moment, the light went on. I got it. My conflict is not with the honor and respect, but with this narrative we've concocted whereby people who serve as police or soldiers or the like are keeping us safe. It creates an "us vs them" dichotomy that I find practically and theologically troubling.

I don't believe in "them." I can't. People are people - as is the theme of most recent posts here, because I've been dwelling a lot on our allegiances and divisions and how we overcome them - we are not separate. There exists only "us." Yes, maybe "us" with some differences, but that describes every human being on the planet - we're all alike, except in ways we're not. Picking and choosing which differences to accentuate and which to ignore don't make a lot of sense. We should recognizing and responding to all the various uniqueness present in everyone around us.

It's a soft play on fear to say a certain group is charging with protecting "us" or "our way of life" or "our freedom." This implies an enemy and it implies weakness; only this other person, other force, has the power to keep me safe. We'll skip the notion of whether safety is something even worth worrying about for today, but it's this way of speaking and, ultimately, thinking and training, that causes so many of our problems today.

What if the primary purpose of a police force was to protect everyone - seeing every human being as equally valuable and important, regardless of their current actions? Would there big as quick a rush to pull the trigger without a "good guys vs bad guys" mentality? That's not to condone behavior or ignore real dangers in the world. I'm not trying to be naive or dismissive, but the notion of "there are bad guys out there who need stopping," is not the only way to look at society and those who fail or refuse to participate in our shared way of life.

Ultimately, that's what an "enemy" is, right? It's a person who has taken a look at the dominant, agreed-upon way of life, and decided to act counter to it. If this counter-action becomes uncomfortable or violent or scary enough, we send in the authorities and remove them. I don't think this process is wrong or flawed or even that it can really be any different, short the parousia or specific divine intervention. I do think, however, that the way in which this process is carried out can be understood and practiced in vastly different ways.

I suspect, most of the time, when someone is arrested, it's for their own good. It's a physical restraint that keeps them from doing even further damage to themselves or others. I wonder, though, if that mindset is less common know than it used to be. The first prisons were literally monasteries. We have the word cell, because that's what you call a room where a monk lives. When someone was being anti-social,

they were sentenced to some time in a cell. They spent time in the regimented life of a cloister, having their needs met in a safe, welcoming,

grace-filled environment, where they could put their head on straight and have time to reflect.

I don't want to get into all the specifics of police of prison reform - there are volumes and volumes of material on these topics and its much too complex to parse in a short space - but I do think there are some simple perceptions we can work on changing to begin a process of Christ-like response to society and those who act outside its bounds.

We must refrain from pronouncing innocence and guilt - I'd say all the time, but especially outside the judicial system - we are all innocent and all guilty, all worthy of reprimand, punishment, and consequences, but also all worthy of grace, love, and human value. We have to start there.

We've also got to boycott the dichotomies - not just us vs them, but good vs evil, and strong vs weak - we've got to fight against the false associations of grace and frailty, love and powerlessness.

If the Kingdom of God is going to have any real impact in our lives, it must penetrate to every aspect of our world and our interactions with it.

Our words matter, our thoughts matter, our perspectives matter. Things are so very rarely black and white, we might as well be prepared for the gray at all times. Life is messy, but love conquers all - we just have to be ready to see the right perspective.

It was the next sentence that struck me difficult. He said, "We prayed a shield of protection around the people who shield and protect us." In that moment, the light went on. I got it. My conflict is not with the honor and respect, but with this narrative we've concocted whereby people who serve as police or soldiers or the like are keeping us safe. It creates an "us vs them" dichotomy that I find practically and theologically troubling.

I don't believe in "them." I can't. People are people - as is the theme of most recent posts here, because I've been dwelling a lot on our allegiances and divisions and how we overcome them - we are not separate. There exists only "us." Yes, maybe "us" with some differences, but that describes every human being on the planet - we're all alike, except in ways we're not. Picking and choosing which differences to accentuate and which to ignore don't make a lot of sense. We should recognizing and responding to all the various uniqueness present in everyone around us.

It's a soft play on fear to say a certain group is charging with protecting "us" or "our way of life" or "our freedom." This implies an enemy and it implies weakness; only this other person, other force, has the power to keep me safe. We'll skip the notion of whether safety is something even worth worrying about for today, but it's this way of speaking and, ultimately, thinking and training, that causes so many of our problems today.

What if the primary purpose of a police force was to protect everyone - seeing every human being as equally valuable and important, regardless of their current actions? Would there big as quick a rush to pull the trigger without a "good guys vs bad guys" mentality? That's not to condone behavior or ignore real dangers in the world. I'm not trying to be naive or dismissive, but the notion of "there are bad guys out there who need stopping," is not the only way to look at society and those who fail or refuse to participate in our shared way of life.

Ultimately, that's what an "enemy" is, right? It's a person who has taken a look at the dominant, agreed-upon way of life, and decided to act counter to it. If this counter-action becomes uncomfortable or violent or scary enough, we send in the authorities and remove them. I don't think this process is wrong or flawed or even that it can really be any different, short the parousia or specific divine intervention. I do think, however, that the way in which this process is carried out can be understood and practiced in vastly different ways.

I suspect, most of the time, when someone is arrested, it's for their own good. It's a physical restraint that keeps them from doing even further damage to themselves or others. I wonder, though, if that mindset is less common know than it used to be. The first prisons were literally monasteries. We have the word cell, because that's what you call a room where a monk lives. When someone was being anti-social,

they were sentenced to some time in a cell. They spent time in the regimented life of a cloister, having their needs met in a safe, welcoming,

grace-filled environment, where they could put their head on straight and have time to reflect.

I don't want to get into all the specifics of police of prison reform - there are volumes and volumes of material on these topics and its much too complex to parse in a short space - but I do think there are some simple perceptions we can work on changing to begin a process of Christ-like response to society and those who act outside its bounds.

We must refrain from pronouncing innocence and guilt - I'd say all the time, but especially outside the judicial system - we are all innocent and all guilty, all worthy of reprimand, punishment, and consequences, but also all worthy of grace, love, and human value. We have to start there.

We've also got to boycott the dichotomies - not just us vs them, but good vs evil, and strong vs weak - we've got to fight against the false associations of grace and frailty, love and powerlessness.

If the Kingdom of God is going to have any real impact in our lives, it must penetrate to every aspect of our world and our interactions with it.

Our words matter, our thoughts matter, our perspectives matter. Things are so very rarely black and white, we might as well be prepared for the gray at all times. Life is messy, but love conquers all - we just have to be ready to see the right perspective.

Tuesday, April 04, 2017

A Selfish Plan to Change the World by Justin Dillon

Disclaimer: I was given a free copy of this book for the purpose of review. My integrity is not for sale. Those who know me well are aware a free book isn't enough to assuage my cutting honesty. If I've failed to write a bad review, it has nothing to do with the source of the material and only with the material itself.

As part of A Selfish Plan to Change the World, author Justin Dillon talks about finding our passions and strengths and leveraging those to change the world for the better. I suspect he would have done well to stick to that plan and have someone else write this book. Dillon has been a successful non-profit innovator and has done tremendous work to combat modern slavery, but the book is a mashup of the history of his organization, Made in a Free World, and some of his personal insights on activism and passion.

The title is catchy, although a bit ill-informed. I agree that doing good for others provides a personal benefit and perhaps this is a solid motivating factor for people to begin to engage in fighting injustice. I'm not sure, however, that this kind of work actually provides the solace and fulfillment Dillon claims. Theologically, I'd argue its only when we give up the fight for fulfillment that we can approach some kind of genuine humanity. This book might be but a mid-level step towards larger goals. But it is a catchy title, for sure.

Dillon is a gifted narrative writer - most chapters open with a story that provides depth and feeling - however when he gets to the part about explaining how that story applies, the metaphors tend to wander and prose gets repetitive. I thought the book would've been stronger if it had focused just on the third section and done more with each narrative; the best work is near the end.

I whole-heartedly endorse Made in a Free World and the need for people to jump in to living out their passions where they are, but I'm not sure I'd recommend this book to anyone for any reason. I do hope it secures Dillon's financial future a bit, though, so he can remain devoted to an incredibly worthy cause.

Disclosure of Material Connection: I received this book free from the publisher through the BookSneeze.com® book review bloggers program. I was not required to write a positive review. The opinions I have expressed are my own. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”