I'm reading this book, The Confidence Game, about the psychology of belief and the ways in which grifters use our biological proclivities to fool us. It's a very interesting book, that uses lots of real examples to illustrate its points,

however, one in particular struck me for an entirely different reason.

Towards the end of the book, the author, Maria Konnikova, presents the case of Glafira Rosales, a small-time art dealer who conned big-time art dealer Ann Freedman into selling off 63 forged abstract expressionist paintings as real over the course of many years, even buying some herself.

The fakes were so convincing, reknowned art experts, historians, even museums specializing in the period and Mark Rothko's son, Christopher,

were convinced they were real. It was only when so many previously unknown works emerged that people began to be suspicious, but it was never because of the art itself.

The book talked about how we can become blind to our own expertise - of course Freedman believed in the art, she had two in her entryway and saw them everyday. How could she, an expert, be fooled by fakes she saw all the time.

In the end the scheme bankrupted a lot of people and embarrassed far more, but that notion of the dealer looking at fake paintings in her entryway struck me as odd - the economics of the whole thing. If those paintings were truly indistinguishable from de Koonig's style (for none of them were copies of existing art, but art in the style of each artist, passed off as unknown), why would it be any less valuable? Either the thing takes on more beauty because the artist is famous, or the art itself is more valuable because the artist is famous - but neither option really makes sense.

It led me to think about the ways in which we evaluate beauty. The high art world is strange to begin with - none of the immense, grotesque values on famous paintings are truly accurate; as in any free-market system, value is determined solely by how much money one is willing to pay. A modern artist can now sell a written description of an un-made work as art, and bag $10m for the privilege of letting someone imagine what they would've designed. I get the inherent value of such a thing, as well as the philosophical statement its making - and I appreciate both - but I don't understand the monetary value.

Beauty is beauty. Someone may be unwilling to part with a beautiful work of art for $10m, when no one else would pay twenty bucks for it, because its beautiful and you can't put a price on beauty. People on Antiques Road Show like to know how much Grandma's 400 year old rocking chair is worth, but they're never going to sell it - the connection is too priceless. I'm sure there are psychological effects at play here, too, but it's also a statement on beauty. What we find valuable doesn't always equate to money.

Shoot, I write here at least once a week, hopefully twice - the hits aren't terrible. I'm sure I could throw some google adsense boxes up and make a few bucks, but I don't like the idea of not being able to control what products get sold next to my thoughts and words. Whatever small benefit I might receive is outweighed by the very non-monetary cost to my perception of artistry and beauty.

In the end, though, it is kind of sad how the free-market has taken over art. Yes, I'm sure some of the people who spend gobs on paintings and sculpture really appreciate the beauty on the pieces and just happen to have the money to buy them; a lot, however, just like the investment.

The book treated the forged paintings as somehow worthless, simply because the artist was not who people thought it to be. Absent that knowledge, no one - absolutely no one - could tell the difference.

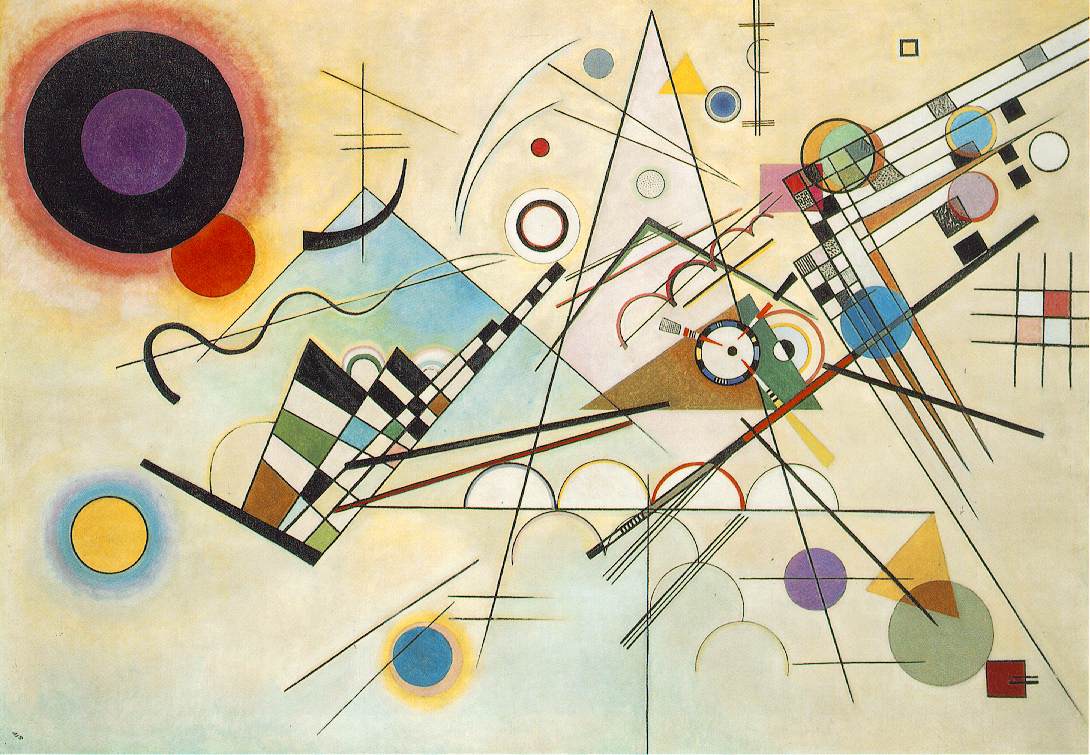

I suppose this could be some grand example of "beauty is truth and truth beauty" right? It is not the artist that makes the painting less valuable, but the deceit? I can see that perspective, but perhaps I'm too naive. I think something beautiful is beautiful. Wasilly Kandinsky is one of my favorite artists. I've seen a lot of his work in person and even more in prints and books. I absolutely love the unusual way his mind and design work - it strikes me as incredibly beautiful. I've also seen a few of his pieces, though, that strike me as downright ugly -

whether its the particular design or the color choices or what have you, I don't like them all simply because he created them.

I get that some Picassos are worth more than others, purportedly because they're better representative of a specific style or a difference in structure or technique - maybe they're even a little less beautiful. But I wonder how they'd be evaluated if the branding of a name weren't attached?

I suppose its impossible to do. Branding is important no matter who you are - JK Rowling continues to use her Robert Galbraith pseudonym for her adult mysteries long after the connection was unmasked. It's branding and removing it probably hinders the artist in some way. At the same time, I wonder how our understanding of beauty and value gets diluted and confounded by the economy of a free market that limits value to simply what money can buy.

No comments:

Post a Comment