I stayed away from Facebook for most of the weekend. I have real trouble forging a path through the inherent tension between my profound admiration for those who would die for a cause and my profound sorrow for those willing to kill for one. It's a trouble not helped by the seeming ease of those around me.

I've written on war and peace and violence before. November 11th was originally Armistice Day, a celebration of the end of war. Over the years it moved to a celebration of those who fight wars and finally to a general celebration of patriotism. It seems like Memorial Day is moving the same direction.

I have known people who died in battle. I have nothing against grieving this loss and celebrating their lives. It is important. A true Memorial Day makes sense. As with Veterans Day, when those who have fought in wars deserve to be remembered and supported through the stress, trauma, and sacrifice of such an ordeal.

However, each year I must pause, I struggle. These days seem to interconnected with a celebration of war and the superiority of our nation. At the very least, there is no appearance of discomfort or ambiguity at what those ideas mean. I've yet to meet a combat veteran who enjoyed celebrating those things; I've met many conflicted by the responses they receive from those on "the outside."

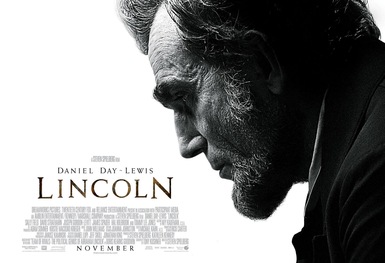

I finally got around to seeing Lincoln last night. Steven Spielberg's masterpiece about the passing of the 13th Amendment. Daniel Day-Lewis truly gives the most remarkable acting performance in the history of film. In the best bio-pics, the actor becomes lost in the character so you forget there's even an actor there at all; with Lincoln, it's is if you never knew. There was not one scene in which I said to myself, "Oh, that's Daniel Day-Lewis." Obviously I never saw or heard Abraham Lincoln, but I might as well have.

The movie is written by the great Tony Kushner, a master of eloquence - and Lincoln's stories and speeches are no exception. There are many times when the audience is roused to emotion on the gravity and importance of the moment. We are lifted on the back of grandiose prose to sail on the best notions of democracy and America.

They left me thinking, "the good is the enemy of the great."

All of our ideals of liberty and freedom are won on the backs of truly horrific pain and death. The opening scene of the film is uncomfortable hand-to-hand combat on a muddy field. It's unfathomable to me that anyone could feel so strongly about anything that they'd be willing to engage in such battle. Spielberg pays lip service to Lincoln's understanding of what he's done, touring battlefields and witnessing the death - yet the movie leaves a clear sense that all of it is worth the higher purpose.

I have a hard time getting excited about ideals being won by the sacrifice of others. Whether it is sending young men and women to war or being willing to kill another. In both instances, we require more from someone else than we do from ourselves. Why is jumping on a live grenade the go-to example of the best in war? It is a clear moment when one man sacrifices more than anyone else.

I thought Lincoln was a beautiful movie. Often these films can be overshadowed by a dominant acting performance, but the rest of the cast is just as strong. They tell a remarkable story about a remarkable man in a remarkable time. There is no doubt about the good present. I just wish they, and the rest of our national culture, would allow for more reflection.

Perhaps Memorial Day isn't the right time for a barbecue and fireworks?

I know we like the certainty of a parade, the same way we enjoy the reverence of a movie like Lincoln. They're helpful ways to deal with difficult realities like war and death, realities like the inequality of the world in which we live. We like having "heroes" among us, to give us confidence that there are better, stronger people out there to do those difficult tasks we could never handle.

Memorial Day has become another part of the patriotic calendar. The one we see played out in the rotating aisle at Wal-Mart - as beach chairs and sunblock give way to costumes and candy, auburn hewed leaves and turkeys, santas and snowmen, roses and hearts, shamrocks, chocolate bunnies, graduation caps, and flag-draped paper plates. We want these notions, these holidays, these events, to become ordinary in their extra-ordinariness.

What struck me uncomfortable about Lincoln, I think, is the same thing that strikes me uncomfortable about civic holidays and celebrations, is the need for an unassailable good.

The problem we have with war and with violence, is that we lack better options for achieving positive ends. Democracy doesn't represent freedom any more than war wins it. The problem is, what freedom we experience, for the most part, comes at the end of a sword or through the legislative process. We recognize the inherent problem with these methods, but lack any framing narrative for something different. Americans once had the same love/hate relationship with war than we now do with government, holding it at arms length with a healthy skepticism. A skepticism earned through the horror of Civil War. It was only after millions lost in two world wars, that things began to change.

I don't think we came around because we decided war was a good thing. We came around because we needed a narrative to justify the loss of so many we loved. We need a Lincoln narrative of universal good to upend the tragedy of Civil War. What could be more good than freedom?

What unsettles me is not that some fight and die in war. It's not the desperate need of those in power to remain there or even the messianic narrative some ascribe to the United States. It's our unwillingness to be wrong.

I have no doubt that those who fought and died, for the most part, did so because they thought it was the best choice they could make in a difficult situation. Being the best choice does not make it necessarily a good choice or a correct choice. We have to be willing to allow for that. In the same way, those who choose non-violence, who speak out against militarism, who are willing to die, but refuse to kill - we know there are problems inherent in that choice as well - may also be making the best choice they could make in a difficult situation. Being the best choice doesn't make it good or right.

There is nothing good about hundreds of thousands dying so millions can be free. We have to move away from using math to make our calculations about life. These people are not numbers, but people - and so are the "enemies" they killed before they died.

Memorial Day is not a happy occasion - neither is the 4th of July for that matter - they're somber events where we can reflect with love on those we've lost, recognize both our mistakes and our successes, and vow to do better in the future.

We cannot hide our unsettledness in celebration. And if we ever cease to be unsettled, we have truly lost.

No comments:

Post a Comment